Curves

Tangents and Normals

Equation of the Tangent

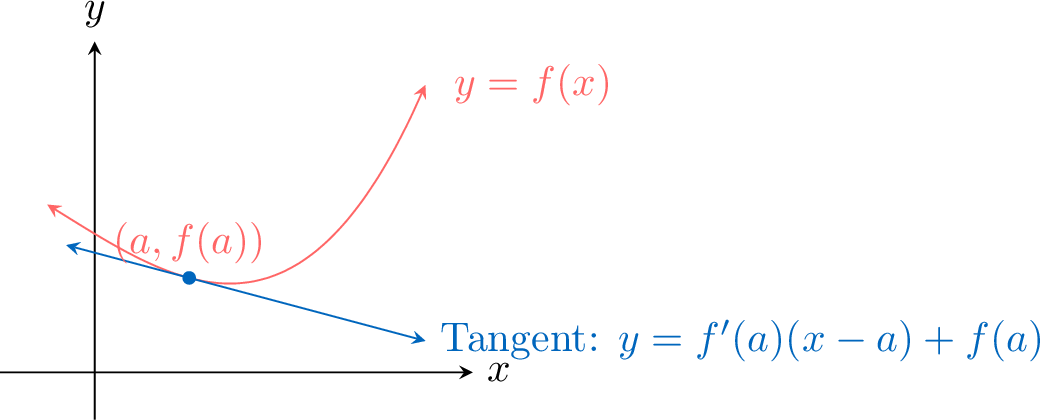

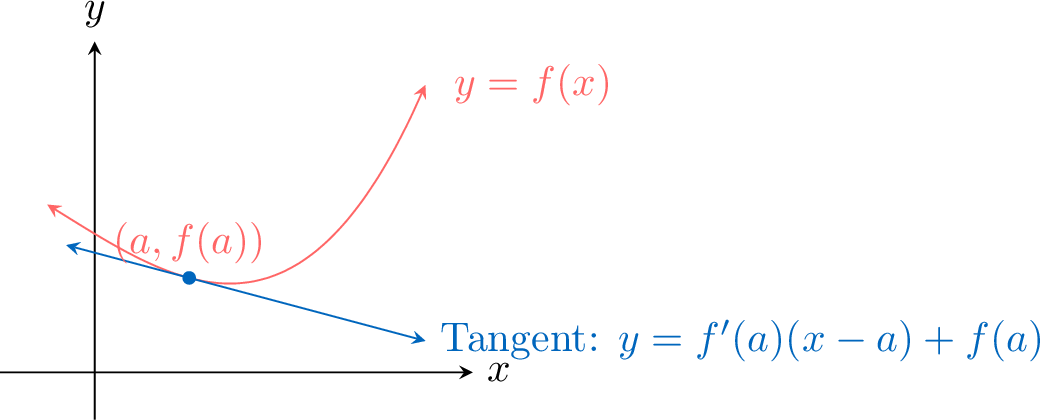

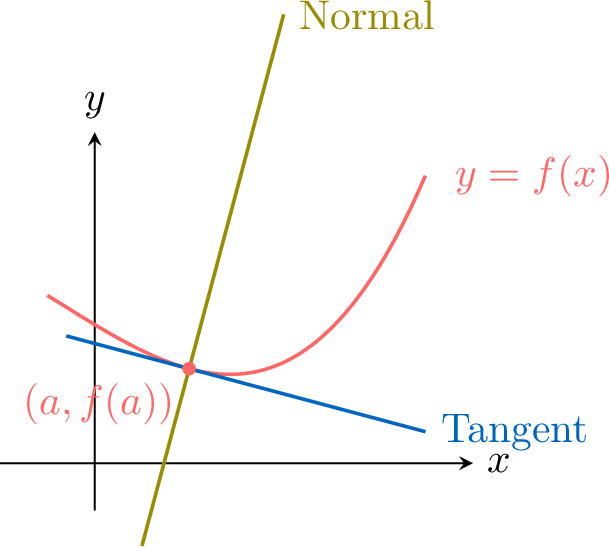

The most direct geometric interpretation of the derivative is that it gives the slope of the tangent line. Finding the equation of this line is a fundamental application of differentiation.

Proposition Equation of the Tangent

Assume \(f\) is differentiable at \(x=a\) and that the tangent is not vertical. Then the equation of the tangent to the curve \(y=f(x)\) at the point \((a, f(a))\) is:$$\textcolor{colorprop}{y = f^{\prime}(a)(x-a) +f(a)}$$

Let \(B(x,y)\) be any point on the tangent line. The point of tangency is \(A(a,f(a))\), which also belongs to the tangent line.

The slope of a line is given by the formula \(m = \dfrac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\). Using points \(A\) and \(B\), the slope of the tangent line is:$$ m = \dfrac{y-f(a)}{x-a}\quad \text{for }x\neq a. $$By definition, the slope of the tangent to the curve \(y=f(x)\) at the point \(x=a\) is the value of the derivative at that point, so:$$ m = f'(a). $$Equating the two expressions for the slope, we get:$$ f'(a) = \dfrac{y-f(a)}{x-a}. $$Multiplying both sides by \((x-a)\) gives the point-slope form of the equation:$$ y - f(a) = f'(a)(x-a). $$This can be rearranged to the slope-intercept form:$$ y = f'(a)(x-a) + f(a). $$

The slope of a line is given by the formula \(m = \dfrac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\). Using points \(A\) and \(B\), the slope of the tangent line is:$$ m = \dfrac{y-f(a)}{x-a}\quad \text{for }x\neq a. $$By definition, the slope of the tangent to the curve \(y=f(x)\) at the point \(x=a\) is the value of the derivative at that point, so:$$ m = f'(a). $$Equating the two expressions for the slope, we get:$$ f'(a) = \dfrac{y-f(a)}{x-a}. $$Multiplying both sides by \((x-a)\) gives the point-slope form of the equation:$$ y - f(a) = f'(a)(x-a). $$This can be rearranged to the slope-intercept form:$$ y = f'(a)(x-a) + f(a). $$

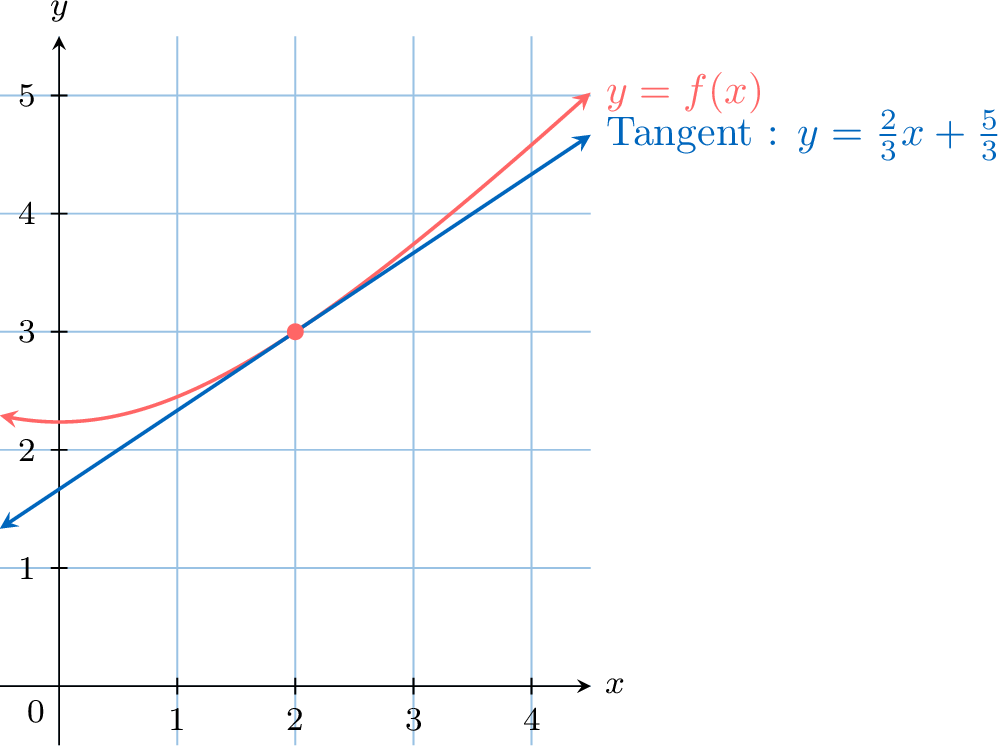

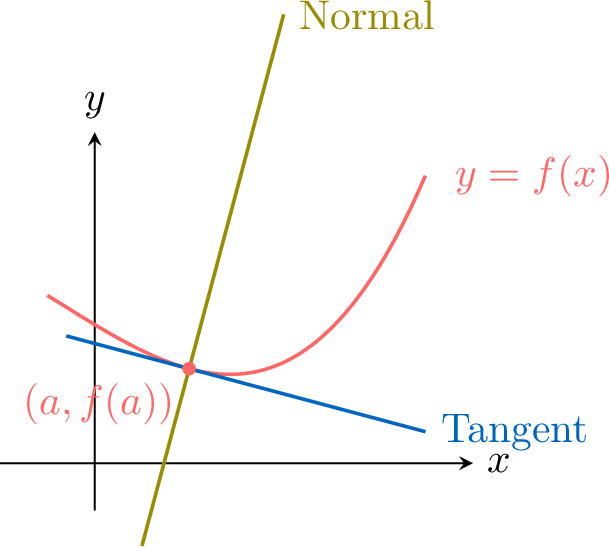

Example

Find the equation of the tangent to \(f(x)=\sqrt{x^{2}+5}\) at \(x=2\).

- Step 1: Find the derivative.

First, rewrite the function as \(f(x) = (x^2+5)^{1/2}\). Using the chain rule: $$\begin{aligned} f'(x) &= \frac{1}{2}(x^2+5)^{-1/2} \cdot (2x)\\ &= \frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2+5}}\end{aligned}$$ - Step 2: Find the coordinates of the point.

At \(x=2\), the \(y\)-coordinate is \(f(2) = \sqrt{2^2+5} = \sqrt{9} = 3\). The point is \((2,3)\). - Step 3: Find the slope of the tangent.

The slope is the value of the derivative at \(x=2\): $$ m = f'(2) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{2^2+5}} = \frac{2}{3}. $$ - Step 4: Write the equation of the line.

$$\begin{aligned} y &= f'(2)(x-2) + f(2)\\ y&=\frac{2}{3}(x-2)+3\\ y &= \frac{2}{3}x + \frac{5}{3}.\\ \end{aligned} $$

Equation of the Normal

Definition Normal Line

The normal line to a curve at a point is the line that is perpendicular to the tangent line at that same point.

Proposition Equation of the Normal

The equation of the normal to the curve \(y=f(x)\) at the point \((a, f(a))\) is given by:

- if \(f'(a)\neq 0\), then the normal has slope \(-\dfrac{1}{f'(a)}\) and $$\textcolor{colorprop}{y = -\frac{1}{f'(a)}(x-a)+f(a)}.$$

- if \(f'(a)= 0\), then the tangent is horizontal and the normal is the vertical line \(x=a\).

- if the tangent is vertical (so its equation is \(x=a\)), then the normal is the horizontal line \(y=f(a)\).

The slope of the tangent at \(x=a\) is \(m_T = f'(a)\). Because the normal line is perpendicular to the tangent line, its slope \(m_N\) is the negative reciprocal of the tangent's slope:$$ m_N = -\frac{1}{m_T} = -\frac{1}{f'(a)} \quad (\text{provided } f'(a) \neq 0). $$Using the point-slope form of a line with the point \((a, f(a))\) and the slope \(m_N\), we get the equation of the normal:$$ y - f(a) = -\frac{1}{f'(a)}(x-a). $$The special cases \(f'(a)=0\) (horizontal tangent) and vertical tangent are handled as described in the statement above.

Example

Find the equation of the normal to \(f(x)=\sqrt{x^{2}+5}\) at \(x=2\).

- Step 1: Find the derivative.

Using the chain rule: $$\begin{aligned} f'(x) &= \frac{1}{2}(x^2+5)^{-1/2} \cdot (2x)\\ &= \frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2+5}}\end{aligned}$$ - Step 2: Find the coordinates of the point.

At \(x=2\), the \(y\)-coordinate is \(f(2) = \sqrt{2^2+5} = \sqrt{9} = 3\). The point is \((2,3)\). - Step 3: Find the slope of the normal.

First, find the slope of the tangent at \(x=2\): $$ m_T = f'(2) = \frac{2}{\sqrt{2^2+5}} = \frac{2}{3}. $$ The slope of the normal is the negative reciprocal: $$ m_N = -\frac{1}{m_T} = -\frac{3}{2}. $$ - Step 4: Write the equation of the normal line. $$\begin{aligned} y &= -\frac{3}{2}(x-2) +3\\ y &= -\frac{3}{2}x + 6. \end{aligned} $$

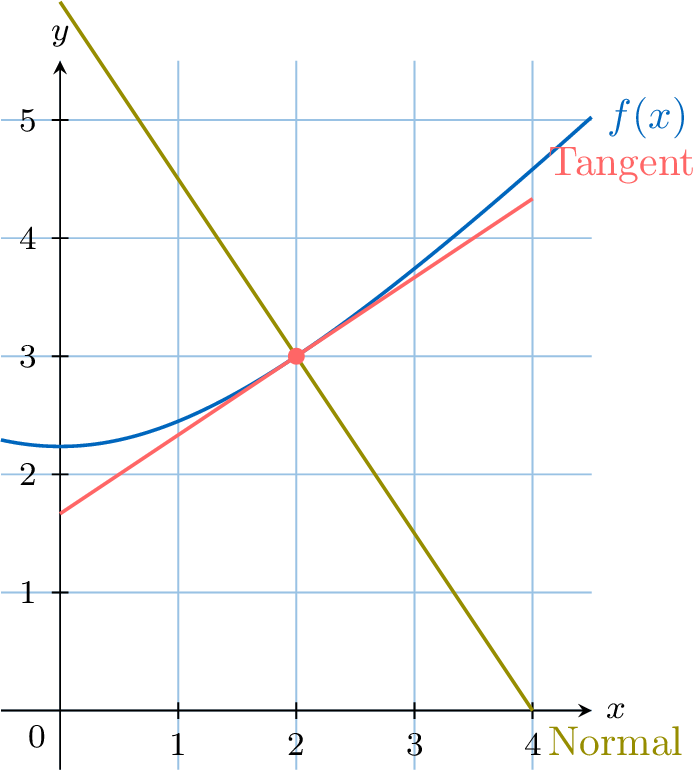

Increasing and Decreasing Functions

Definition

When we draw the graph of a function, we may notice that the function is increasing or decreasing over particular intervals.

Definition Increasing and Decreasing Functions

Let \(I\) be an interval contained in the domain of a function \(f\).

- \(f\) is increasing on \(I\) if for all \(x_1, x_2 \in I\) such that \(x_1 < x_2\), we have \(f(x_1) < f(x_2)\).

- \(f\) is decreasing on \(I\) if for all \(x_1, x_2 \in I\) such that \(x_1 < x_2\), we have \(f(x_1) > f(x_2)\).

Example

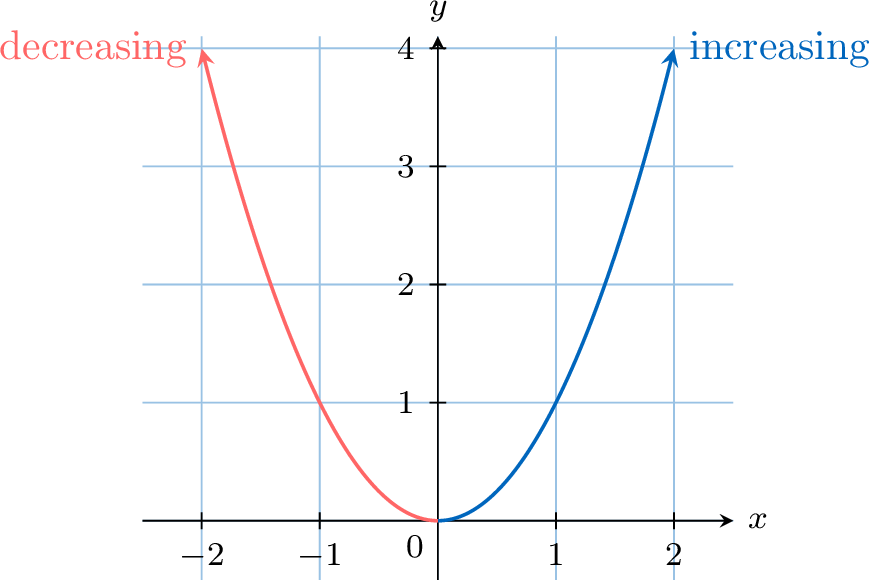

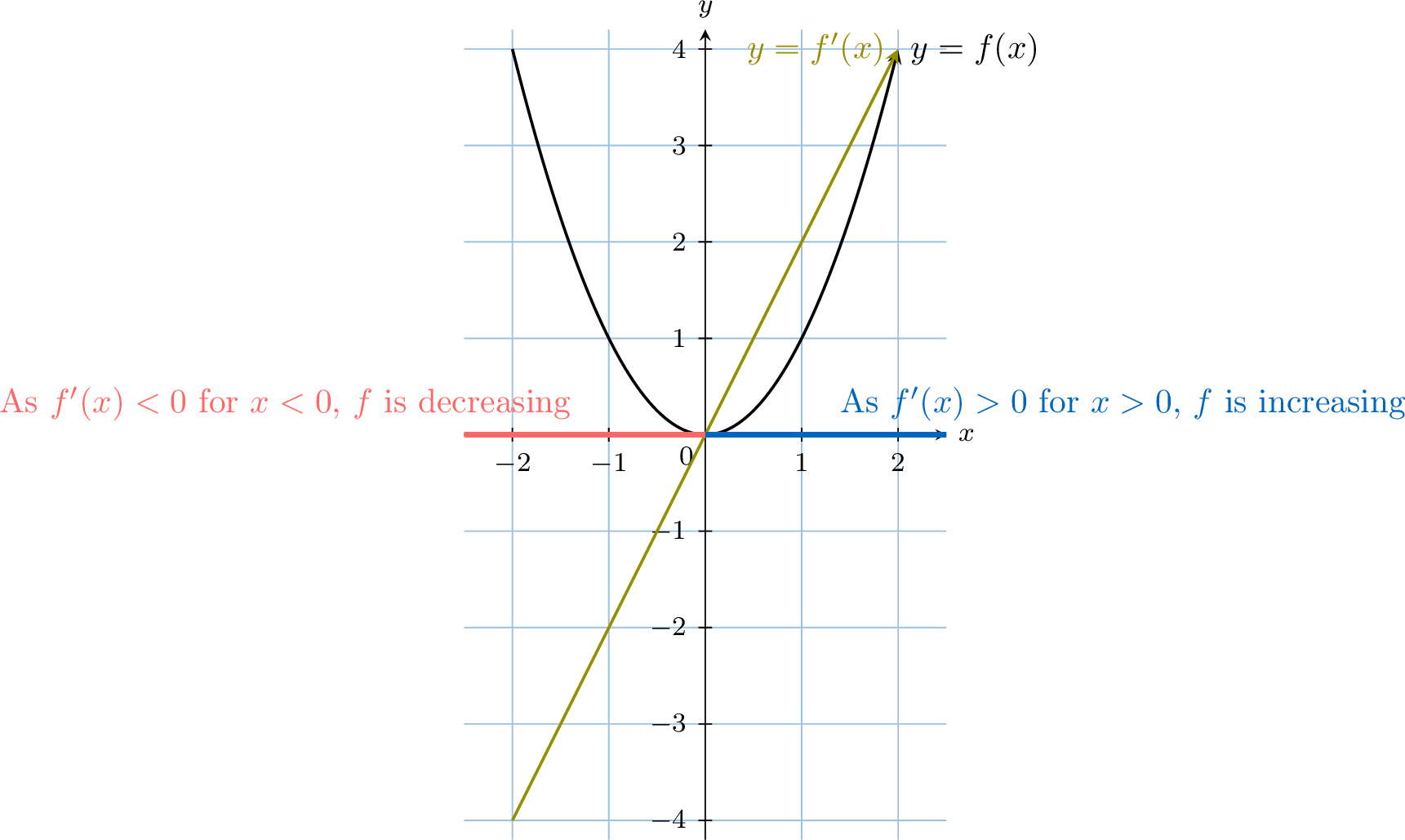

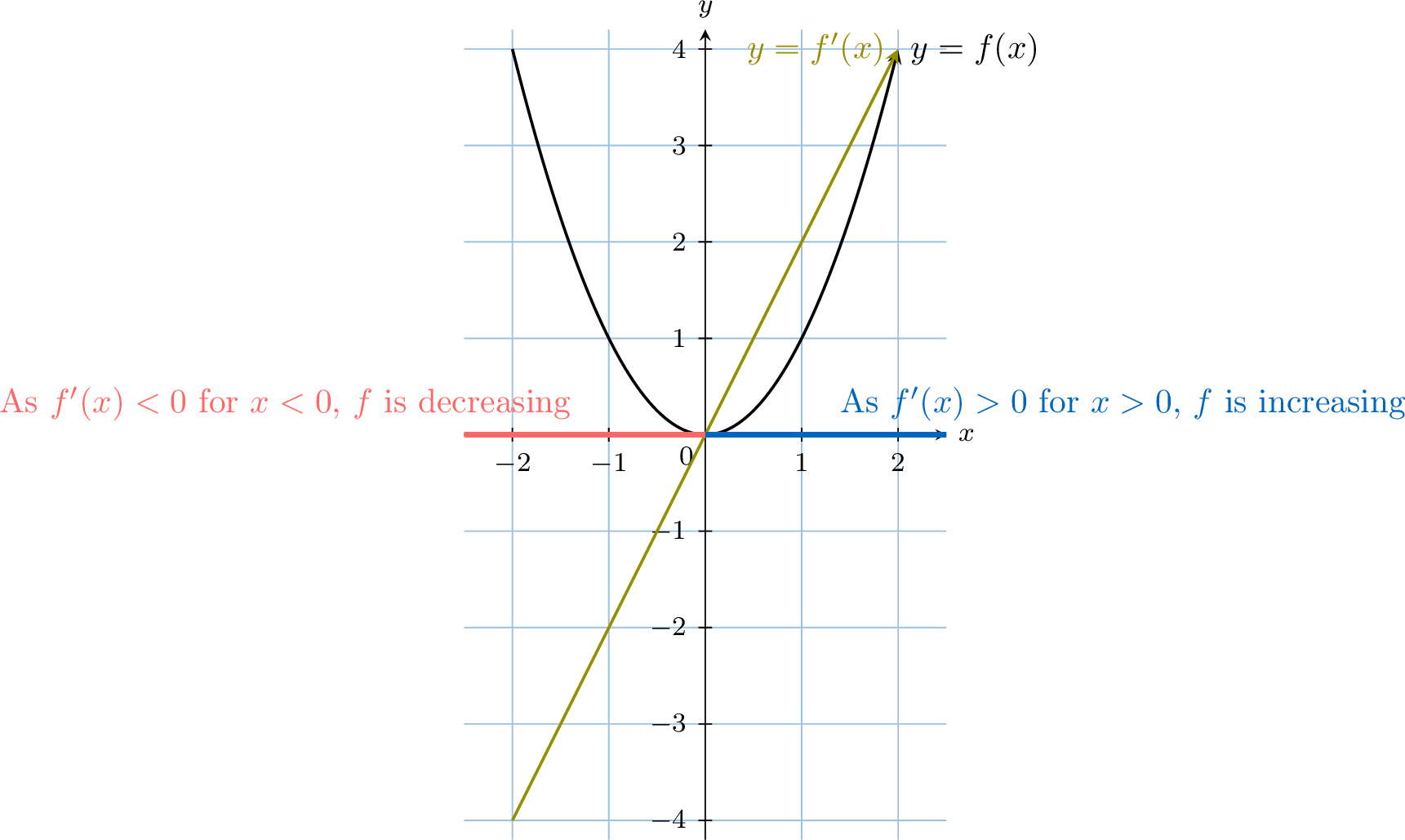

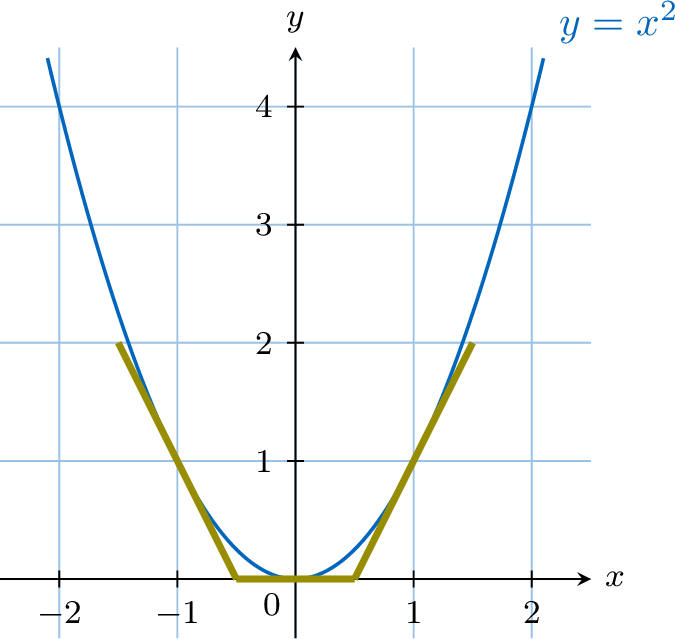

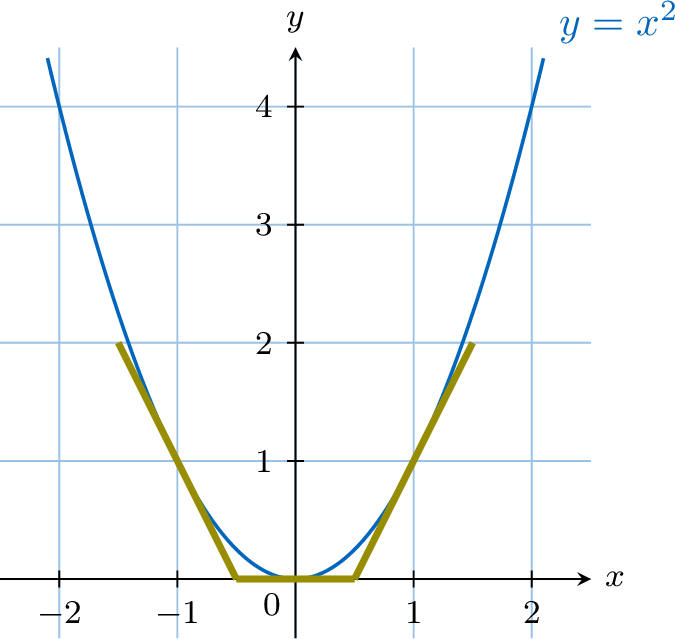

The function \(f(x) = x^2\) is decreasing on the interval \((-\infty, 0)\) and increasing on the interval \((0, \infty)\).

First Derivative Test

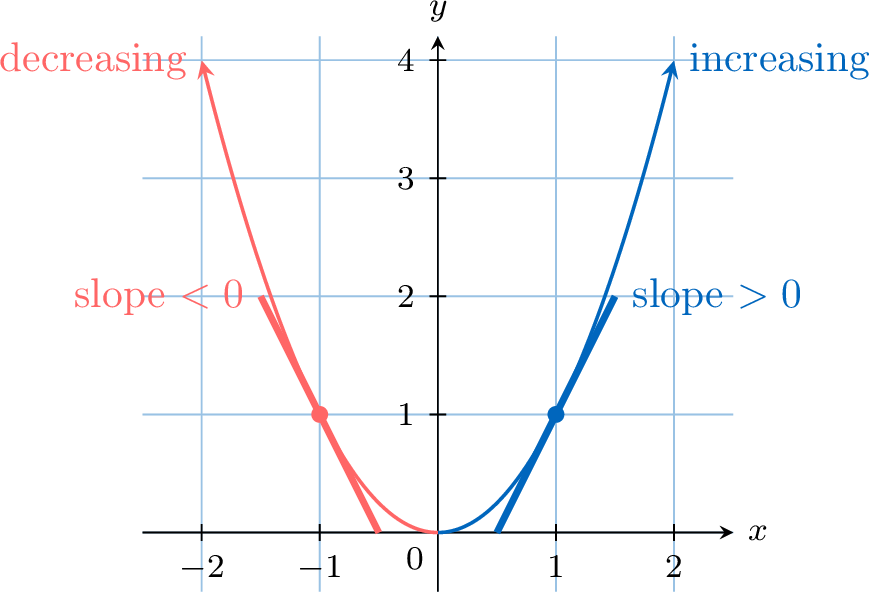

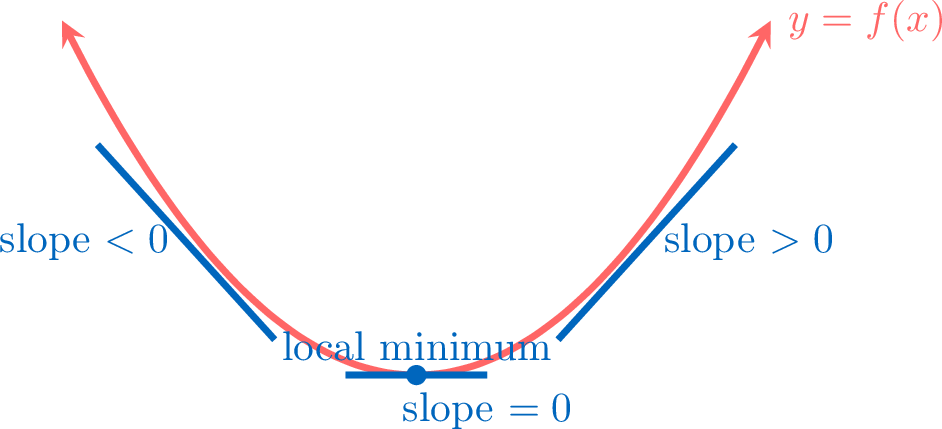

The derivative of a function, \(f'\), gives the slope of the tangent at any point on the curve \(y=f(x)\). This allows us to determine the intervals where the function is increasing or decreasing.

A function is increasing where the slope of its tangent is positive, and decreasing where the slope of its tangent is negative.

A function is increasing where the slope of its tangent is positive, and decreasing where the slope of its tangent is negative.

Proposition First Derivative Test

For a function \(f\) that is differentiable on an interval \(I\):

- If \(f'(x) > 0\) for all \(x \in I\), then \(f\) is increasing on \(I\).

- If \(f'(x) < 0\) for all \(x \in I\), then \(f\) is decreasing on \(I\).

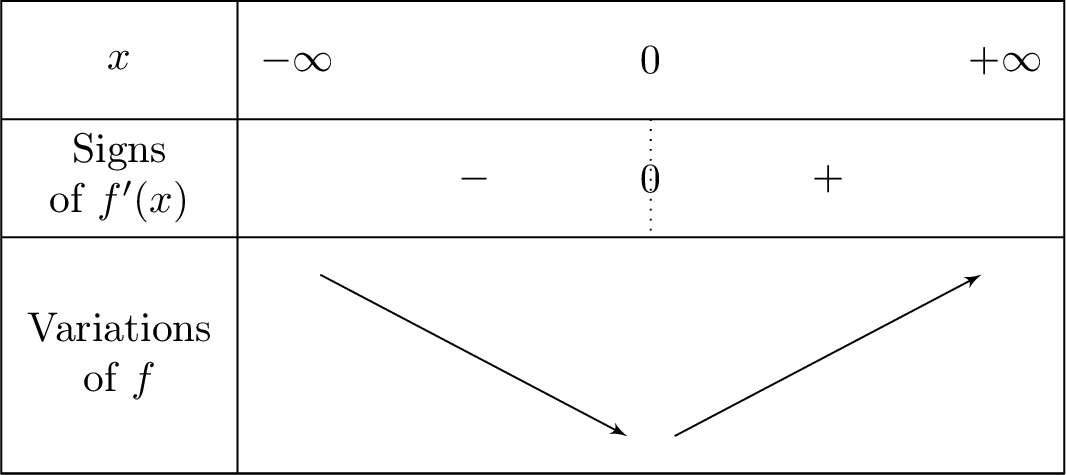

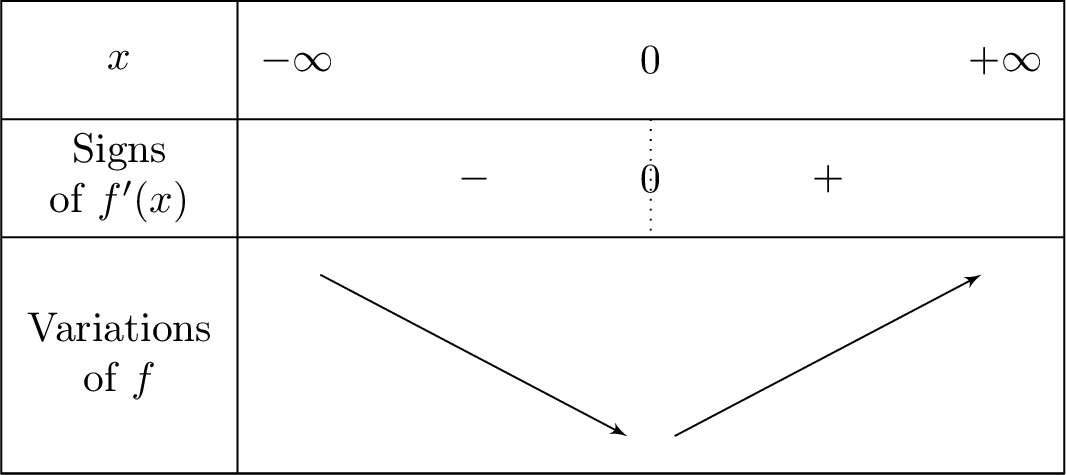

Method Sign Diagram and Table of Variations

A sign diagram for the derivative, \(f'\), shows where the function is increasing or decreasing. This information is organized in a table of variations.

Example

Find the variations of the function \(f(x)=x^2\).

The derivative of the function \(f(x)=x^2\) is \(f'(x)=2x\).

- The derivative \(f'(x)\) is negative on \((-\infty, 0)\), so the function \(f(x)\) is decreasing on \((-\infty, 0)\).

- The derivative \(f'(x)\) is positive on \((0,+\infty)\), so the function \(f(x)\) is increasing on \((0,+\infty)\).

Extrema of Functions

Definitions

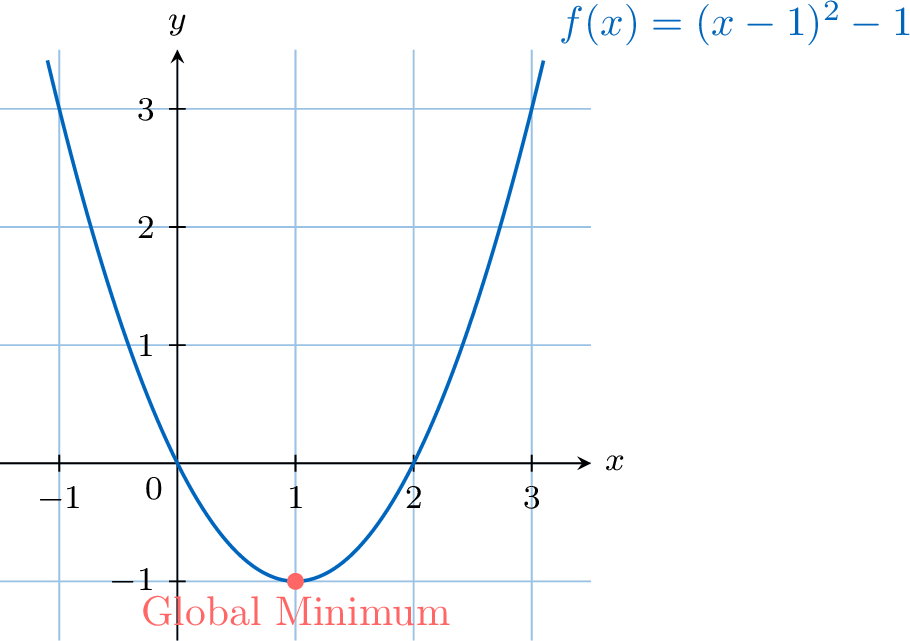

Definition Global Extrema

Let \(f\) be a function with domain \(D\).

- \(f\) has a global maximum at \(x=c\) if \(f(c) \ge f(x)\) for all \(x\) in \(D\). The value \(f(c)\) is the maximum value of \(f\).

- \(f\) has a global minimum at \(x=c\) if \(f(c) \le f(x)\) for all \(x\) in \(D\). The value \(f(c)\) is the minimum value of \(f\).

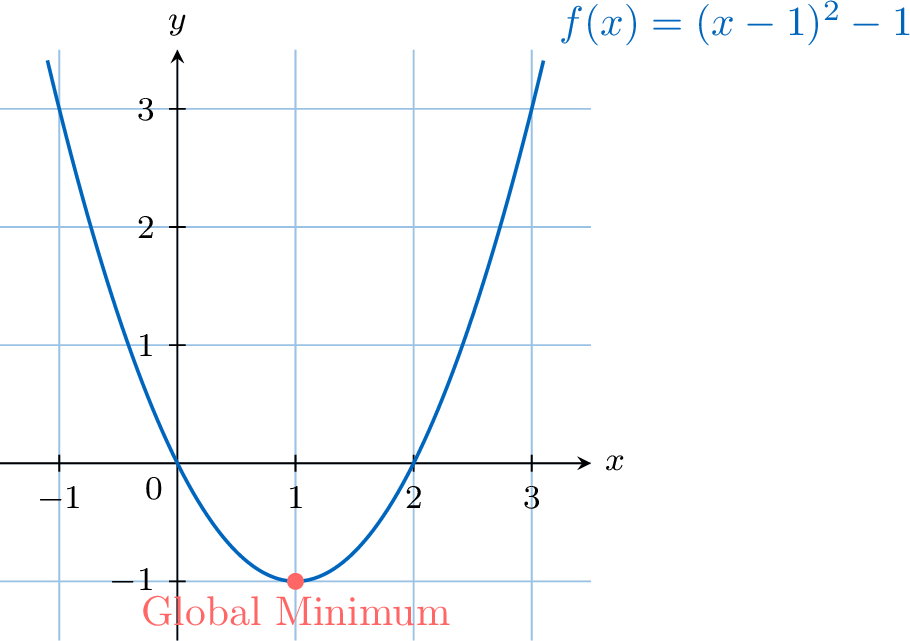

Example

For \(f(x)=(x-1)^2-1\), the point \((1,-1)\) is a global minimum, since \(f(x) \ge f(1)\) for all \(x \in \mathbb{R}\).

Definition Local Extrema

Let \(f\) be a function.

- \(f\) has a local maximum at \(x=c\) if there is an open interval \(I\) containing \(c\) such that \(f(c) \ge f(x)\) for all \(x\) in \(I\).

- \(f\) has a local minimum at \(x=c\) if there is an open interval \(I\) containing \(c\) such that \(f(c) \le f(x)\) for all \(x\) in \(I\).

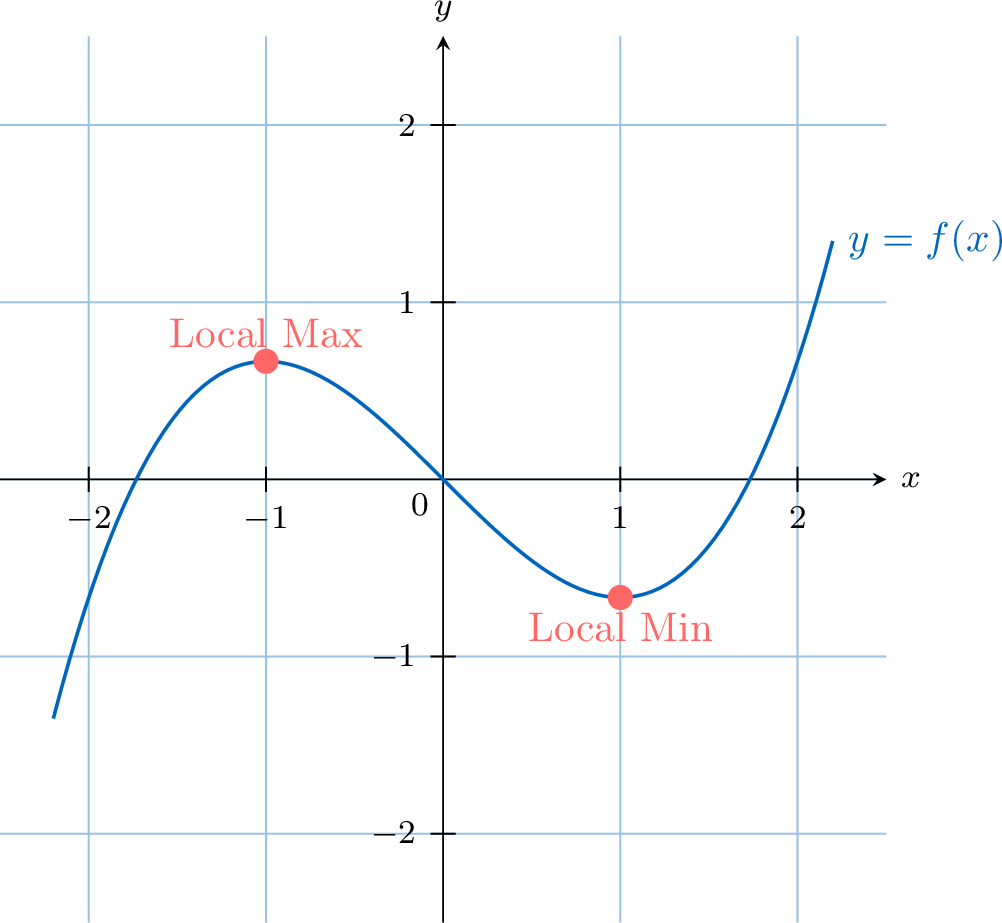

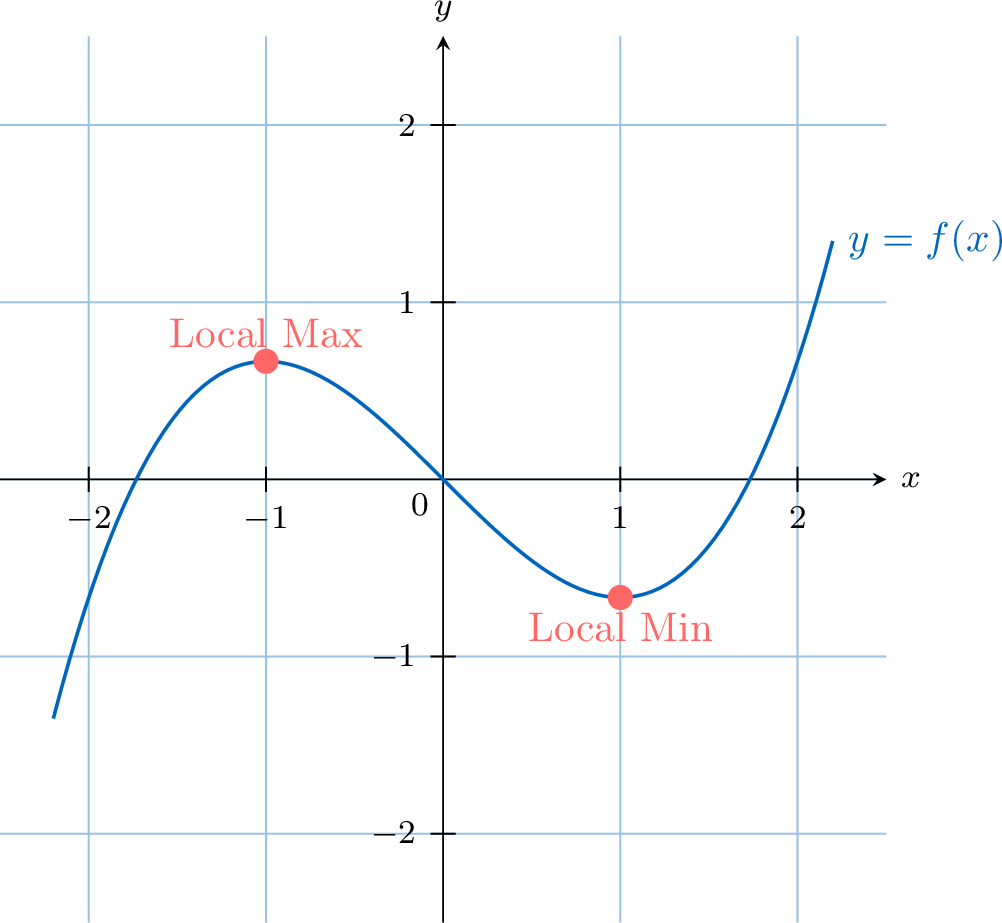

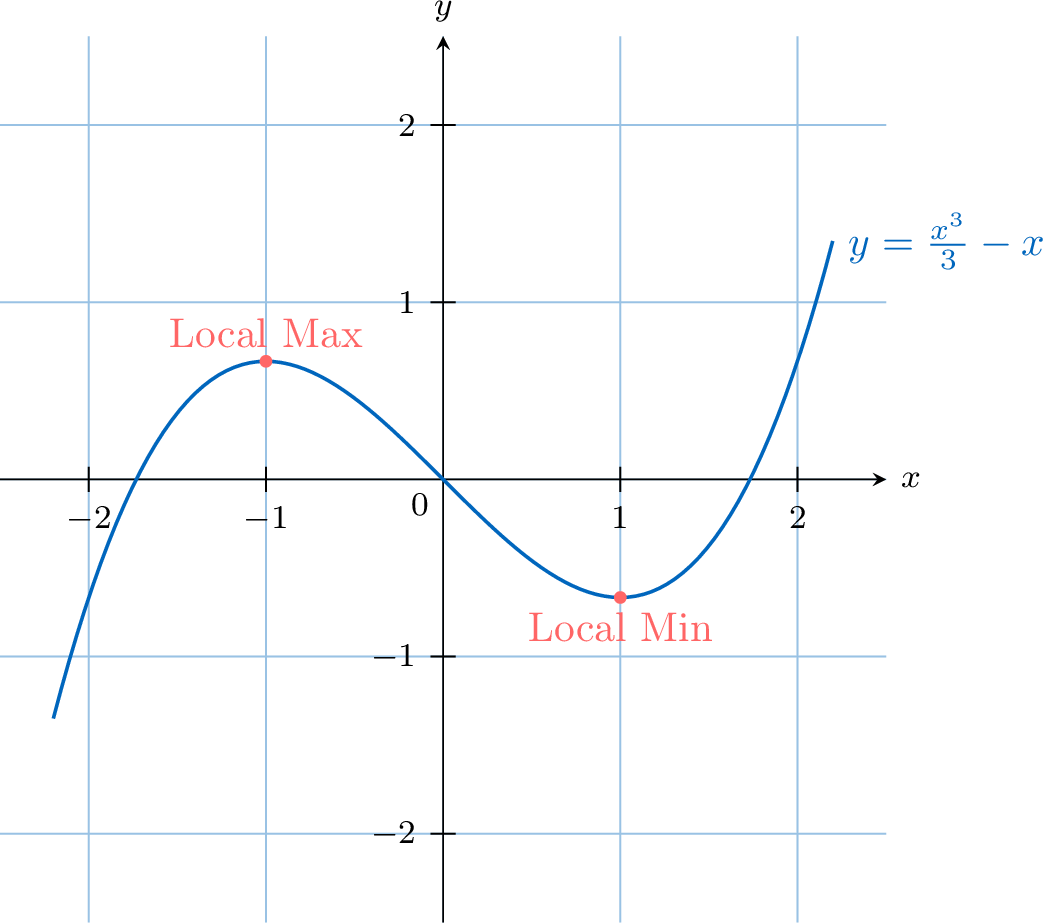

Example

The function \(f(x) = \frac{x^3}{3} - x\) has a local maximum at \(x=-1\) and a local minimum at \(x=1\).

First Derivative Test for Local Extrema

Definition Stationary Point

A stationary point of a function \(f\) is a point \((c, f(c))\) on the curve where the tangent is horizontal, which means \(f^{\prime}(c)=0\).

Proposition Local Extrema and Stationary Points

Let \(f\) be a function defined on an open interval \(I\), and let \(c\in I\).

If \(f\) has a local maximum or a local minimum at \(x=c\) and if \(f\) is differentiable at \(c\), then$$ f'(c)=0. $$

If \(f\) has a local maximum or a local minimum at \(x=c\) and if \(f\) is differentiable at \(c\), then$$ f'(c)=0. $$

This proposition shows that any local maximum or minimum of a differentiable function (at an interior point of the interval) must occur at a stationary point, that is, a point where \(f'(c)=0\).

In practice, this means that stationary points are candidates for local maxima and minima:

In practice, this means that stationary points are candidates for local maxima and minima:

- First, solve \(f'(x)=0\) to find all stationary points.

- Then, for each stationary point, use the sign of \(f'\) (or a table of variations, or the second derivative) to decide whether it is a local maximum, a local minimum, or neither (for example, a point of inflection).

Proposition First Derivative Test for Local Extrema

Let \(c\) be a stationary point such that \(f'(c)=0\).

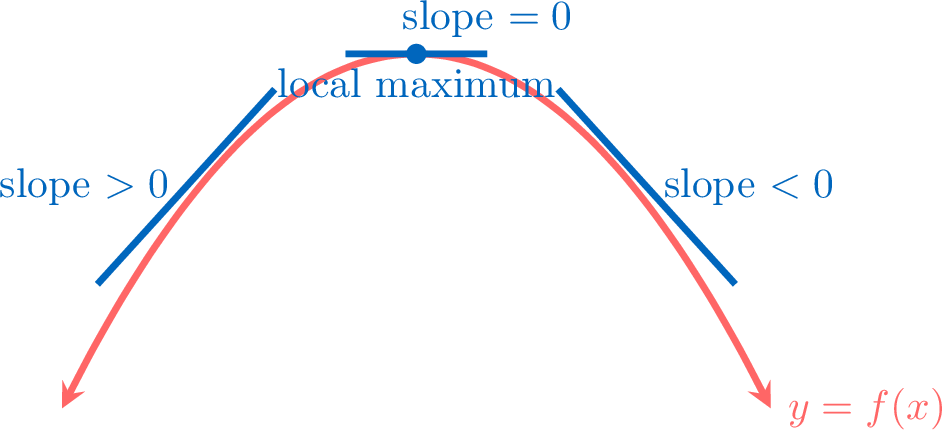

- If \(f^{\prime}(x)\) changes sign from positive to negative at \(x=c\), then \(f\) has a local maximum at \(c\).

- If \(f^{\prime}(x)\) changes sign from negative to positive at \(x=c\), then \(f\) has a local minimum at \(c\).

Example

Find and classify the stationary points of \(f(x) = \frac{1}{3}x^3 - x\).

- Find the derivative:$$ f'(x) = x^2 - 1. $$

- Find stationary points by solving \(f'(x)=0\):$$ \begin{aligned} x^2 - 1 &= 0 \\ (x-1)(x+1) &= 0.\end{aligned}$$The stationary points are at \(x=-1\) and \(x=1\).

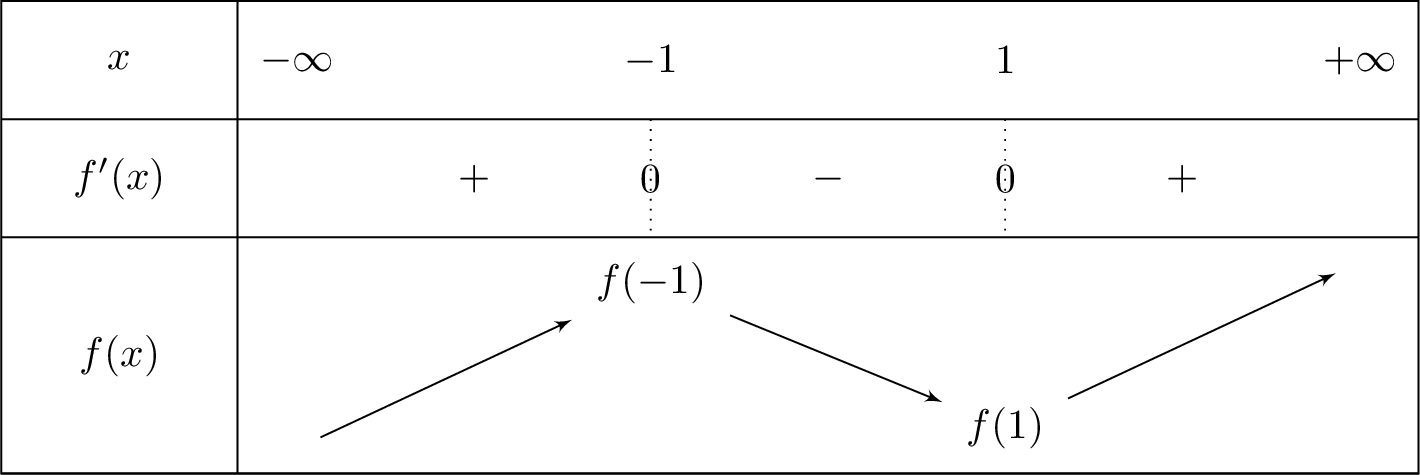

- Create the sign diagram for \(f'(x)\):

The derivative \(f'(x)=x^2-1\) is an upward-opening parabola with roots at \(-1\) and \(1\). It is positive outside the roots and negative between them. - Draw the table of variations and classify points:

- At \(x=-1\), the sign of \(f'(x)\) changes from \(+\) to \(-\). Thus, there is a local maximum at \(x=-1\).$$f(-1) = \frac{1}{3}(-1)^3 - (-1) = \frac{2}{3}.$$

- At \(x=1\), the sign of \(f'(x)\) changes from \(-\) to \(+\). Thus, there is a local minimum at \(x=1\).$$f(1) = \frac{1}{3}(1)^3 - 1 = -\frac{2}{3}.$$

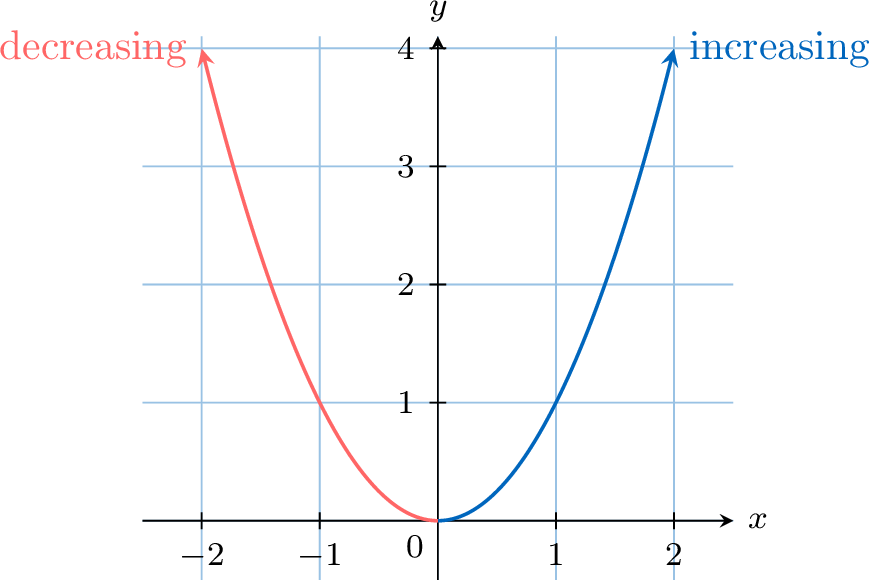

Concavity

Definition

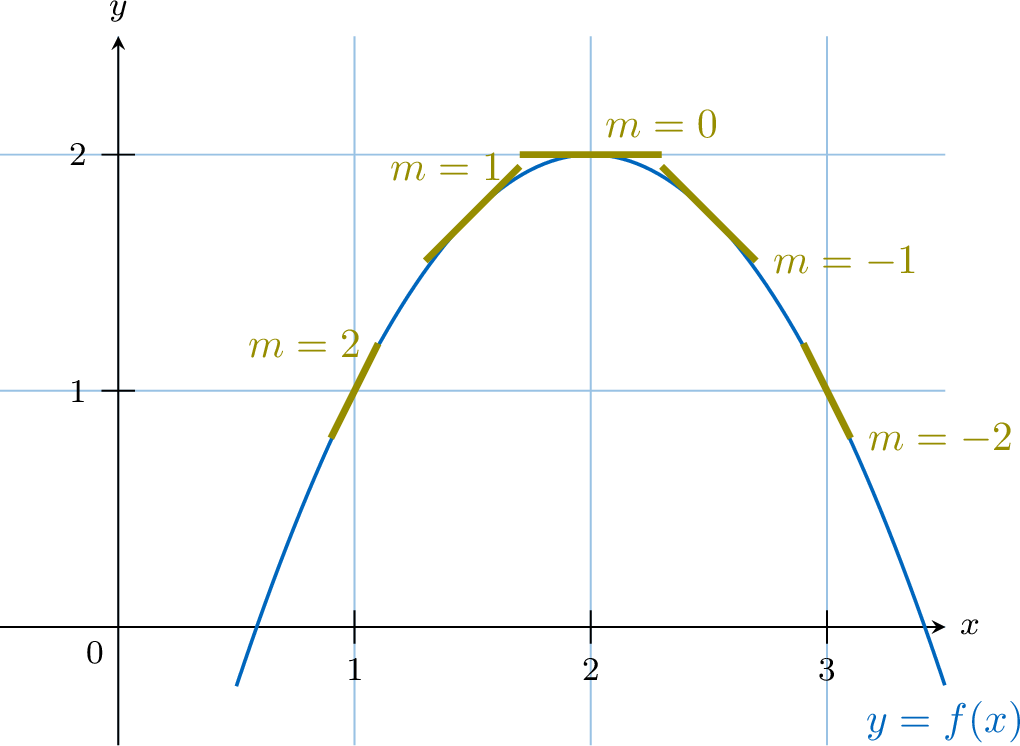

We have seen that the first derivative, \(f'(x)\), gives the slope of the curve \(y=f(x)\) at any value of \(x\).

The second derivative, \(f''(x)\), tells us the rate of change of the slope. It therefore gives us information about the shape or curvature of the curve.

The second derivative, \(f''(x)\), tells us the rate of change of the slope. It therefore gives us information about the shape or curvature of the curve.

Definition Concavity

A function \(f\) is:

- concave up on an interval if its graph bends upwards, like a cup

. The tangents lie below the curve.

. The tangents lie below the curve. - concave down on an interval if its graph bends downwards, like a cap

. The tangents lie above the curve.

. The tangents lie above the curve.

Example

The curve \(f(x)=x^2\) is always concave up. The tangents lie below the curve.

Second Derivative Test for Concavity

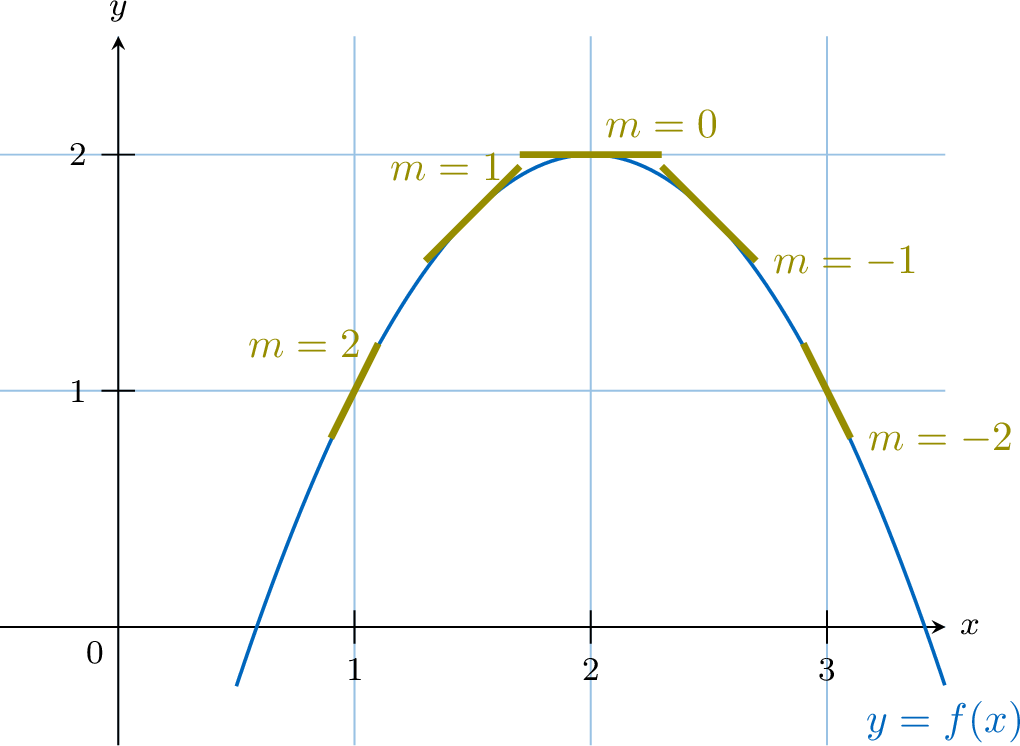

Consider the curve below, which is concave down.

This means that the derivative function, \(f'\), is a decreasing function. If \(f'\) is decreasing, then its own derivative satisfies \(f''(x)\leq 0\) (where defined).

This means that the derivative function, \(f'\), is a decreasing function. If \(f'\) is decreasing, then its own derivative satisfies \(f''(x)\leq 0\) (where defined).

Proposition Second Derivative Test for Concavity

For a function \(f\) that is twice differentiable on an interval \(I\):

- \(f''(x) \ge 0\) for all \(x \in I\), if and only if \(f\) is concave up on \(I\).

- \(f''(x) \le 0\) for all \(x \in I\), if and only if \(f\) is concave down on \(I\).

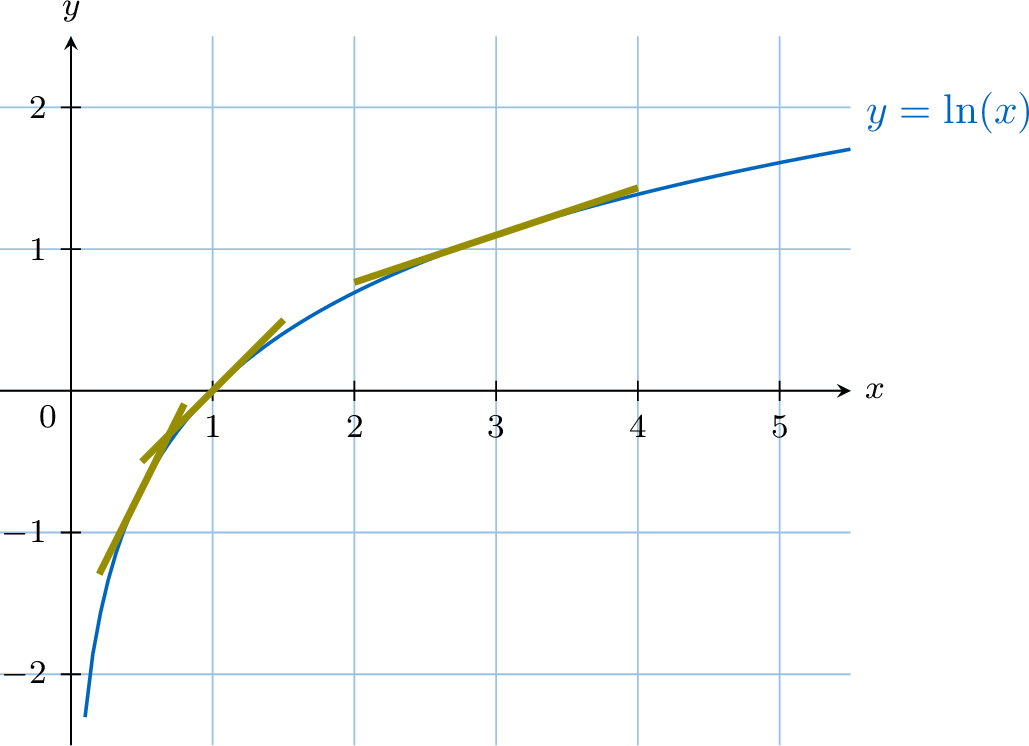

Example

Show that \(f(x)=\ln(x)\) is concave down on its domain.

The domain of \(f(x)=\ln(x)\) is \((0,+\infty)\).

We find the first and second derivatives:$$ f'(x)=\frac 1 x \quad \text{and} \quad f''(x)=-\frac{1}{x^2}. $$For all \(x\) in the domain, \(x^2 > 0\), which means \(-\dfrac{1}{x^2} < 0\).

Since \(f''(x) < 0\) for all \(x \in (0, +\infty)\), the function is concave down on its entire domain.

We find the first and second derivatives:$$ f'(x)=\frac 1 x \quad \text{and} \quad f''(x)=-\frac{1}{x^2}. $$For all \(x\) in the domain, \(x^2 > 0\), which means \(-\dfrac{1}{x^2} < 0\).

Since \(f''(x) < 0\) for all \(x \in (0, +\infty)\), the function is concave down on its entire domain.

Points of Inflection

Definition

A point of inflection marks a subtle but important change in the behavior of a function. While the function may still be increasing or decreasing, the rate at which it does so changes from accelerating to decelerating, or vice versa.

Consider the total number of cases during the start of an epidemic. Initially, the number of new cases per day increases, meaning the curve of total cases is steepening (concave up). At some point, measures are taken and the number of new cases per day, while still positive, starts to decrease. The curve of total cases begins to flatten (concave down). The moment this transition occurs is the point of inflection. It is the point where the rate of growth is at its maximum.

Consider the total number of cases during the start of an epidemic. Initially, the number of new cases per day increases, meaning the curve of total cases is steepening (concave up). At some point, measures are taken and the number of new cases per day, while still positive, starts to decrease. The curve of total cases begins to flatten (concave down). The moment this transition occurs is the point of inflection. It is the point where the rate of growth is at its maximum.

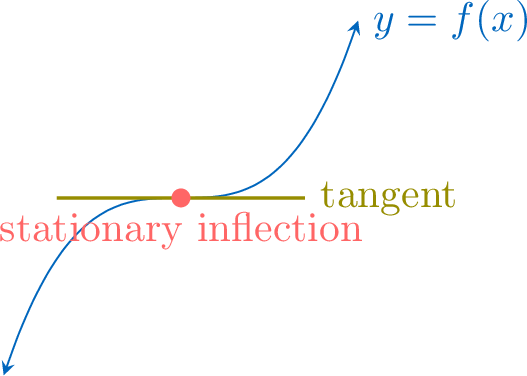

Definition Point of Inflection

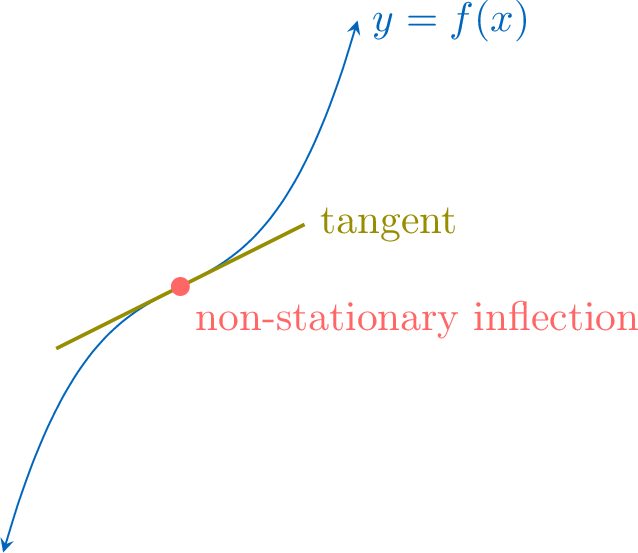

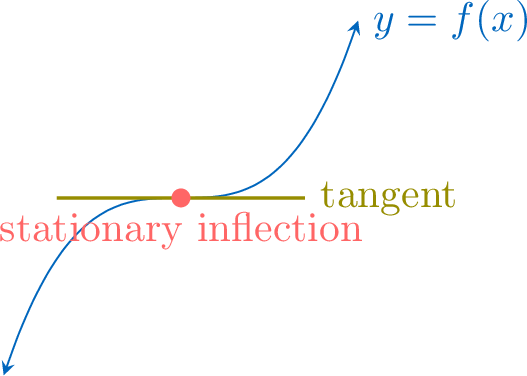

A point of inflection is a point on a curve where the concavity changes (from up to down, or from down to up). The tangent line crosses the curve at that point.  \(\quad\)

\(\quad\)

An inflection point is stationary if the tangent is horizontal. It is non-stationary if the tangent is not horizontal.

\(\quad\)

\(\quad\)

Second Derivative Test for Points of Inflection

Since concavity is determined by the sign of the second derivative \(f''(x)\), a point of inflection must occur where \(f''(x)\) changes sign. For this to happen, \(f''\) must be zero at that point.

Proposition Second Derivative Test for a Point of Inflection

A point \((a, f(a))\) is a point of inflection if \(f''(a)=0\) and the sign of \(f''(x)\) changes at \(x=a\).

The point of inflection is:

The point of inflection is:

- stationary if \(f'(a)=0\).

- non-stationary if \(f'(a) \neq 0\).

Example

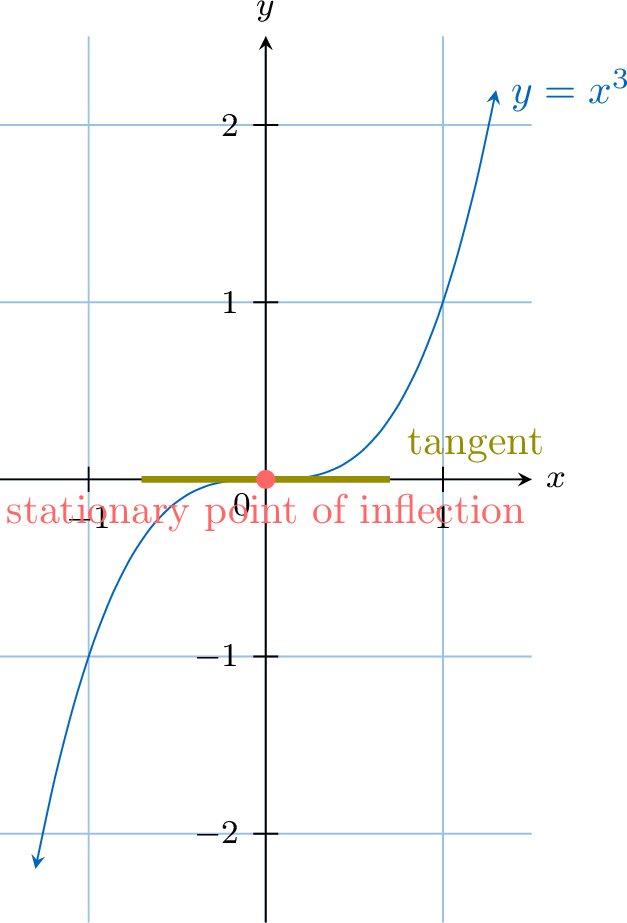

For \(f(x)=x^3\), find and classify the point of inflection.

- Find first and second derivatives:$$ f'(x) = 3x^2 $$$$ f''(x) = 6x. $$

- Find potential inflection points by solving \(f''(x)=0\):$$ 6x = 0 \implies x=0. $$

- Check for sign change in \(f''(x)\) at \(x=0\):

- For \(x<0\), \(f''(x) = 6x < 0\) (concave down).

- For \(x>0\), \(f''(x) = 6x > 0\) (concave up).

- Classify the inflection point:

We check the value of the first derivative at \(x=0\):$$ f'(0) = 3(0)^2 = 0. $$Since \(f'(0)=0\), the point \((0,0)\) is a stationary point of inflection.