Probability

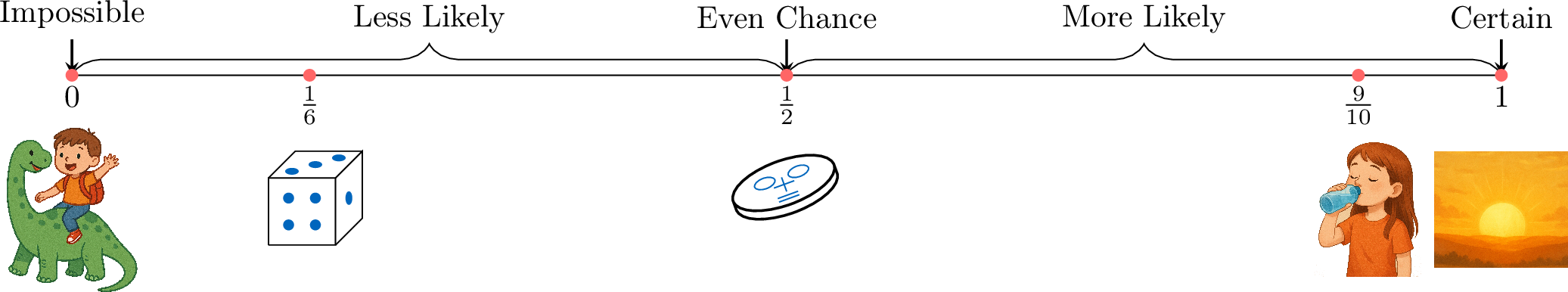

Ever wondered if it will rain tomorrow or if you will win a game? That’s probability! It is a mathematical way to measure how likely an event is to happen.

Algebra of Events

Sample Spaces

Definition Outcome

An outcome is one possible result of a random experiment.

Example

What are all the possible outcomes when you flip a coin?

The outcomes are Heads (H) =  and Tails (T) =

and Tails (T) =  .

.

Example

What are the outcomes when you roll a six-sided die?

The outcomes are\(1 = \) ,\(2 = \)

,\(2 = \) ,\(3 = \)

,\(3 = \) ,\(4 = \)

,\(4 = \) ,\(5 = \)

,\(5 = \) and \(6 = \)

and \(6 = \) .

.

Definition Sample Space

The sample space is the set of all possible outcomes of a random experiment.

Example

What’s the sample space when you flip a coin?

The sample space is \(\{\text{Heads}, \text{Tails}\} = \{\) ,

, \(\}\), or just \(\{\text{H}, \text{T}\}\) for short.

\(\}\), or just \(\{\text{H}, \text{T}\}\) for short.

Example

What’s the sample space when you roll a six-sided die?

The sample space is \(\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\} = \{\) ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, \(\}\).

\(\}\).

Events

Definition Event

An event (often denoted by a capital letter like \(E\)) is a subset of the sample space.

Example

For the experiment of rolling a die, list the outcomes in the event \(E\): “rolling an even number”.

Among the outcomes of the sample space \(\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\} = \{\) ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, \(\}\), the event of rolling an even number is\(E = \{2, 4, 6\} = \{\)

\(\}\), the event of rolling an even number is\(E = \{2, 4, 6\} = \{\) ,

, ,

, \(\}\).

\(\}\).

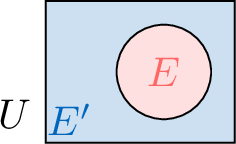

Complementary Events

In probability, it is often useful to consider the outcomes that do not belong to a specific event. This set of “other” outcomes is known as the complementary event. It represents everything in the sample space that is outside the original event. The complement of an event \(E\) is denoted by \(E'\).

Definition Complementary Event

The complementary event of an event \(E\), denoted \(E'\), \(E^c\), or \(\overline{E}\), is the set of all outcomes in the sample space that are not in \(E\).

Example

In the experiment of rolling a fair six-sided die, let \(E\) be the event “rolling an even number”. Find the complementary event, \(E'\).

The sample space is \(\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\} = \{\) ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, ,

, \(\}\).

\(\}\).

The event is \(E = \{2, 4, 6\} = \{\) ,

, ,

, \(\}\).

\(\}\).

The complementary event \(E'\) contains all outcomes in the sample space that are not in \(E\).

Therefore, \(E' = \{1, 3, 5\} = \{\) ,

, ,

, \(\}\). This is the event “rolling an odd number”.

\(\}\). This is the event “rolling an odd number”.

The event is \(E = \{2, 4, 6\} = \{\)

The complementary event \(E'\) contains all outcomes in the sample space that are not in \(E\).

Therefore, \(E' = \{1, 3, 5\} = \{\)

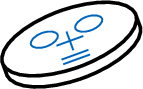

Multi-Step Random Experiments

A multi-step experiment is a random experiment made up of a sequence of two or more simple steps. For example, flipping two coins is a multi-step experiment composed of two actions: flipping the first coin and then flipping the second.

In many multi-step experiments, we can find the total number of possible outcomes by multiplying the number of outcomes at each step. To display all the combined outcomes, we can use tools like lists, tables, or tree diagrams.

In many multi-step experiments, we can find the total number of possible outcomes by multiplying the number of outcomes at each step. To display all the combined outcomes, we can use tools like lists, tables, or tree diagrams.

Method Representing Sample Spaces for Multi-Step Experiments

When an experiment has more than one step, the sample space can be represented in several ways:

- by listing all possible ordered outcomes;

- using a table (best for two-step experiments);

- using a tree diagram (useful for any number of steps).

Example

For the experiment of tossing two coins, represent the sample space by:

- listing all possible outcomes;

- using a table;

- using a tree diagram.

- List:

Each outcome records the result of coin 1 first, then coin 2:$$\{\textcolor{colordef}{H}\textcolor{colorprop}{H}, \textcolor{colordef}{H}\textcolor{colorprop}{T}, \textcolor{colordef}{T}\textcolor{colorprop}{H}, \textcolor{colordef}{T}\textcolor{colorprop}{T}\}$$ - Table:

\(\begin{aligned} & \textcolor{colorprop}{\text{coin 2}} \\ \textcolor{colordef}{\text{coin 1}} \end{aligned} \) \(\textcolor{colorprop}{H}\) \(\textcolor{colorprop}{T}\) \(\textcolor{colordef}{H}\) \(\textcolor{colordef}{H}\textcolor{colorprop}{H}\) \(\textcolor{colordef}{H}\textcolor{colorprop}{T}\) \(\textcolor{colordef}{T}\) \(\textcolor{colordef}{T}\textcolor{colorprop}{H}\) \(\textcolor{colordef}{T}\textcolor{colorprop}{T}\) - Tree diagram:

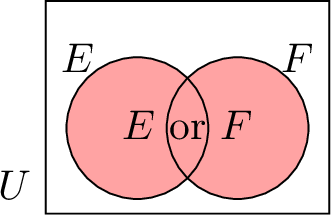

\(E\) or \(F\)

Definition \(E\) or \(F\)

The union of two events \(E\) and \(F\), denoted \(E \cup F\), is the event that occurs if \(E\) occurs, or \(F\) occurs, or both occur. We read this as "E or F". It includes all outcomes that are in at least one of the events.

Example

A standard six-sided die is rolled. Let event \(E\) be "rolling an even number" and event \(F\) be "rolling a number less than 4". Find the event \(E \cup F\).

The events are \(E = \{2, 4, 6\}\) and \(F = \{1, 2, 3\}\).

The union \(E \cup F\) contains all outcomes that appear in either set, without repetition:$$ E \cup F = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 6\}. $$

The union \(E \cup F\) contains all outcomes that appear in either set, without repetition:$$ E \cup F = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 6\}. $$

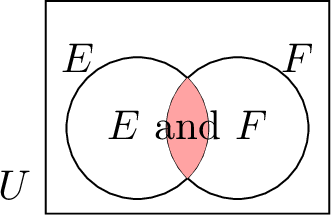

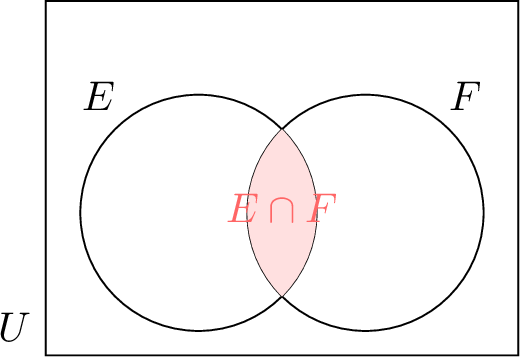

\(E\) and \(F\)

Definition \(E\) and \(F\)

The intersection of two events \(E\) and \(F\), denoted \(E \cap F\), is the event that occurs if both \(E\) and \(F\) occur simultaneously. We read this as "E and F". It includes all outcomes that are common to both events.

Example

A standard six-sided die is rolled. Let event \(E\) be "rolling an odd number" and event \(F\) be "rolling a number less than 4". Find the event \(E \cap F\).

The events are \(E = \{1, 3, 5\}\) and \(F = \{1, 2, 3\}\).

The intersection \(E \cap F\) contains only the outcomes that are in both sets:$$ E \cap F = \{1, 3\}. $$

The intersection \(E \cap F\) contains only the outcomes that are in both sets:$$ E \cap F = \{1, 3\}. $$

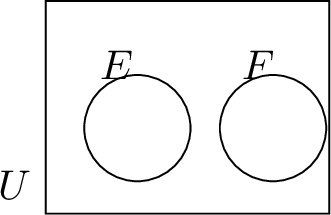

Mutually Exclusive

Definition Mutually Exclusive

Two events \(E\) and \(F\) are mutually exclusive (or disjoint) if they have no outcomes in common. This means they cannot occur at the same time. Their intersection is the empty set (\(\emptyset\)):$$E \cap F = \emptyset.$$

Example

When rolling a die, let \(E\) be the event "rolling an odd number" and \(F\) be the event "rolling an even number". Show that \(E\) and \(F\) are mutually exclusive.

The event sets are \(E = \{1, 3, 5\}\) and \(F = \{2, 4, 6\}\).

We find their intersection:$$ E \cap F = \emptyset. $$Since there are no outcomes common to both events, they are mutually exclusive.

We find their intersection:$$ E \cap F = \emptyset. $$Since there are no outcomes common to both events, they are mutually exclusive.

Venn Diagram

Definition Set Theory and Probability Vocabulary

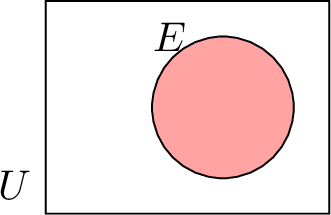

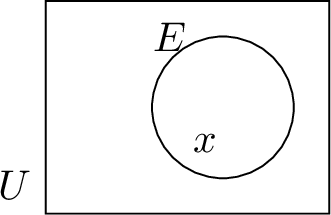

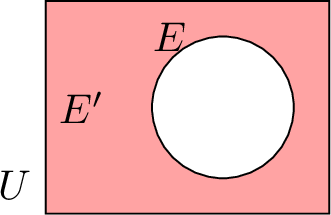

| Notation | Set Vocabulary | Probability Vocabulary | Venn Diagram |

| \(U\) | Universal set | Sample space |  |

| \(x\) | Element of \(U\) | Outcome |  |

| \(\emptyset\) | Empty set | Impossible event | |

| \(E\) | Subset of \(U\) | Event |  |

| \(x \in E\) | \(x\) is an element of \(E\) | \(x\) is an outcome of \(E\) |  |

| \(E'\) | Complement of \(E\) in \(U\) | Complement of \(E\) in \(U\) |  |

| \(E \text{ or } F\) | Union of \(E\) and \(F\): \(E \cup F\) | \(E\) or \(F\) |  |

| \(E \text{ and } F\) | Intersection of \(E\) and \(F\): \(E \cap F\) | \(E\) and \(F\) |  |

| \(E \cap F = \emptyset\) | \(E\) and \(F\) are disjoint | \(E\) and \(F\) are mutually exclusive |  |

Axioms and Rules of Probability

Axioms of Probability

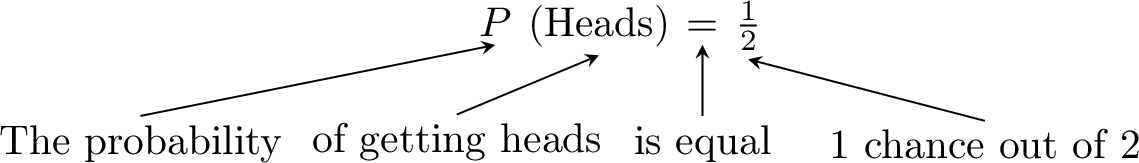

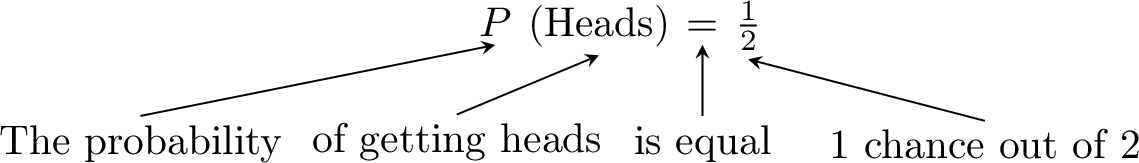

When you flip a coin, there are two possible outcomes: heads or tails. The chance of getting heads is 1 out of 2. We can write this as a fraction:

Definition Probability

The probability of an event \(E\), written \(P(E)\), is a number that tells us how likely the event is to happen. It is always between \(0\) (impossible) and \(1\) (certain). In other words, for any event \(E\), we have \(0 \leq P(E) \leq 1\).

All of probability is built upon three fundamental rules called axioms. These are statements we accept as true and from which all other rules can be derived. The probability of an event \(E\), denoted \(P(E)\), is a number that quantifies its likelihood.

Definition Probability Axioms

A function \(P\) is a probability measure if it satisfies the following three axioms for any events \(E\) and \(F\) in a sample space \(U\):

- Axiom 1 (Non-negativity): The probability of any event is a non-negative number, between 0 and 1 inclusive. $$0 \leqslant P(E) \leqslant 1$$

- Axiom 2 (Total Probability): The probability of the entire sample space is 1. $$P(U) = 1$$

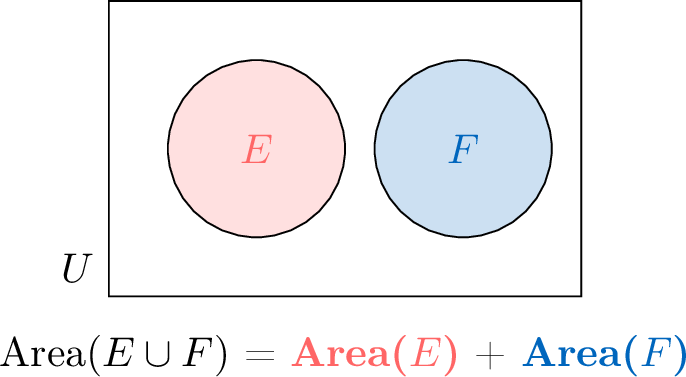

- Axiom 3 (Additivity for Mutually Exclusive Events): If two events \(E\) and \(F\) are mutually exclusive (\(E \cap F = \emptyset\)), then the probability of their union is the sum of their individual probabilities. $$P(E \cup F) = P(E) + P(F)$$

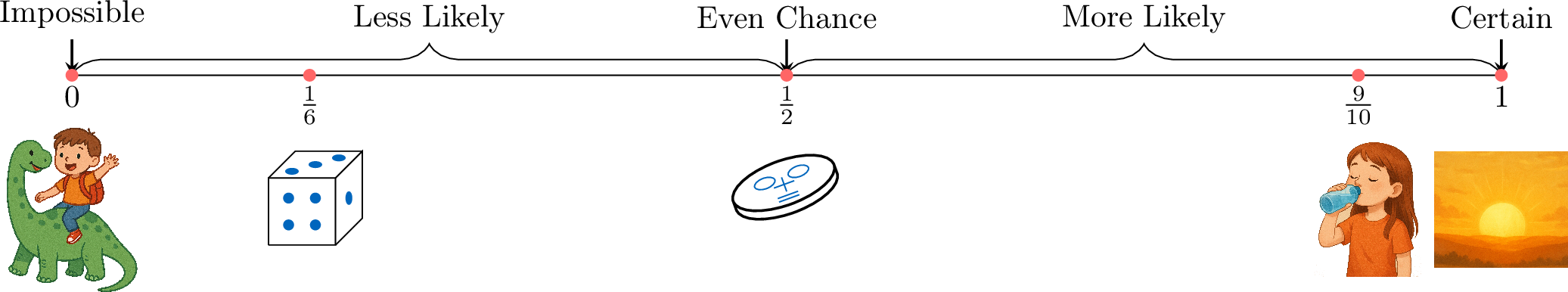

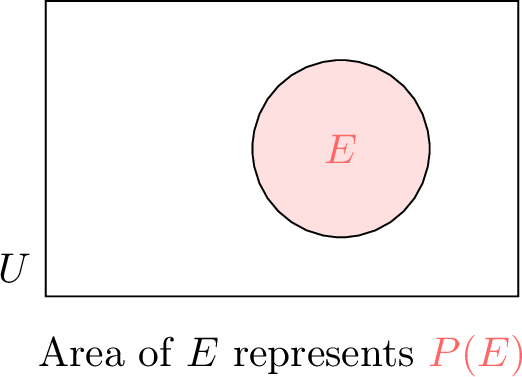

Visualizing the Axioms with Venn Diagrams

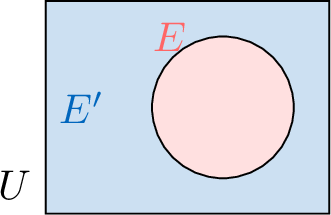

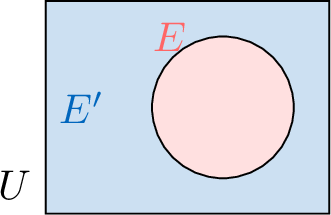

Venn diagrams can help us understand the probability axioms. In this context, the entire area of the universal set \(U\) is considered to have a total probability of 1. The probability of any event \(E\) is represented by the proportion of the total area that the event covers.

- Axiom 1: \(0 \leqslant P(E) \leqslant 1\)

The area representing event \(E\) cannot be smaller than nothing (0) and cannot be larger than the entire sample space (1).

- Axiom 2: \(P(U) = 1\)

It is certain that some outcome in the sample space occurs. Therefore, the probability of the entire sample space is 1 (or 100\(\pourcent\)).

- Axiom 3: \(P(E \cup F) = P(E) + P(F)\) for Mutually Exclusive Events

If two events \(E\) and \(F\) are mutually exclusive, they do not overlap in the Venn diagram. The total area covered by their union (\(E \cup F\)) is simply the sum of their individual areas.

Fundamental Probability Rules

If there is a \(40\pourcent\) chance of rain tomorrow, what is the chance that it will not rain?\(100\pourcent - 40\pourcent = 60\pourcent\) This calculation is an application of the complement rule. It is a shortcut to find the probability that an event does not happen.

Proposition Complement Rule

For any event \(E\) and its complementary event \(E'\),$$\textcolor{colorprop}{P(E') = 1 - P(E)}$$

- Algebraic Proof

By definition, an event \(E\) and its complement \(E'\) are mutually exclusive (\(E \cap E' = \emptyset\)) and their union is the entire sample space (\(E \cup E' = U\)).

Using Axiom 3: \(P(E \cup E') = P(E) + P(E')\).

Using Axiom 2: \(P(U) = 1\).

Since \(E \cup E' = U\), we can equate their probabilities:$$ P(E) + P(E') = P(U) = 1. $$Rearranging the formula gives the complement rule:$$P(E') = 1 - P(E).$$ - Geometric Proof

The total area of the sample space, \(\textcolor{olive}{P(U)}\), ,is the sum of the area of the event, \textcolor{colordef}{\(P(E)\)}, and the area of its complement, \textcolor{colorprop}{\(P(E')\)}.

,is the sum of the area of the event, \textcolor{colordef}{\(P(E)\)}, and the area of its complement, \textcolor{colorprop}{\(P(E')\)}.

So,$$\textcolor{colordef}{P(E)} + \textcolor{colorprop}{P(E')} = \textcolor{olive}{P(U)}.$$Since \(\textcolor{olive}{P(U) = 1}\) (from Axiom 2), we have:$$\textcolor{colordef}{P(E)} + \textcolor{colorprop}{P(E')} = 1.$$

Example

Farid has a \(0.8\) (\(80\pourcent\)) chance of finishing his homework on time tonight (event \(E\)). What is the probability that he does not finish on time?

The complementary event \(E'\) is “Farid does not finish his homework on time”. Using the complement rule:$$\begin{aligned}P(E') &= 1 - P(E) \\

&= 1 - 0.8 \\

&= 0.2\end{aligned}$$There is a \(0.2\) (or \(20\pourcent\)) probability that he does not finish on time.

Proposition Addition Law of Probability

For any two events \(E\) and \(F\),$$\textcolor{colorprop}{P(E \cup F) = P(E) + P(F) - P(E \cap F)}$$This formula holds whether or not \(E\) and \(F\) are mutually exclusive. If they are mutually exclusive, then \(P(E \cap F) = 0\) and the formula reduces to Axiom 3.

The Venn diagram below shows the sample space \(U\) with two intersecting events, \(E\) and \(F\).

Therefore, the total probability of the union is$$P(E \cup F) = P(E) + P(F) - P(E \cap F).$$

Therefore, the total probability of the union is$$P(E \cup F) = P(E) + P(F) - P(E \cap F).$$

Example

A local high school is holding a talent show. The probability that a randomly selected student participates in singing is \(0.4\), the probability that a student participates in dancing is \(0.3\), and the probability that a student participates in both singing and dancing is \(0.1\). Find the probability that a randomly selected student participates in either singing or dancing.

Let \(S\) be the event "participates in singing" and \(D\) be the event "participates in dancing". We are given:

- \(P(S) = 0.4\)

- \(P(D) = 0.3\)

- \(P(S \cap D) = 0.1\)

Equally Likely

Have you ever flipped a fair coin or rolled a fair die? In these experiments, each outcome is just as likely as the others. We call these equally likely outcomes.

Definition Equally Likely

When all outcomes are equally likely, the probability of an event \(E\) is:$$\textcolor{colordef}{\begin{aligned}P(E) &= \frac{\text{number of outcomes in the event}}{\text{number of outcomes in the sample space}}\\

&=\dfrac{\Card{E}}{\Card{U}}\\

\end{aligned}}$$

Example

What’s the probability of rolling an even number with a fair six-sided die?

- Sample space \(= \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\}\) (6 outcomes).

- \(E = \{2, 4, 6\}\) (3 outcomes).

- $$\begin{aligned}P(E) &= \frac{3}{6} \\ &= \frac{1}{2} \end{aligned}$$

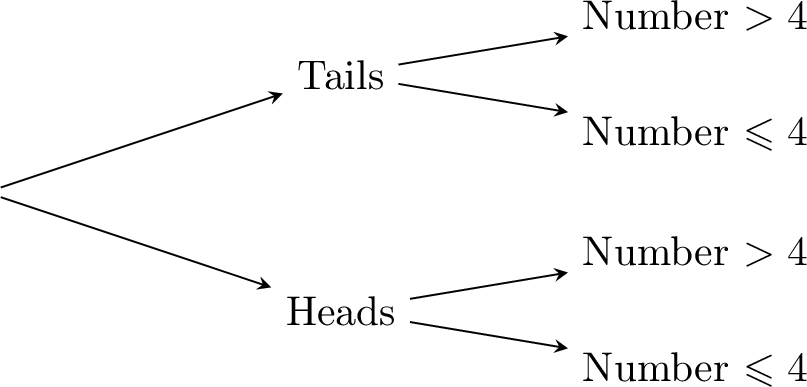

Probability of Independent Events

Independent events are events where knowing that one event has happened does not change the probability that the other event happens. For example, when rolling two fair dice at the same time, the result of the first die does not change the chances for the second die — they are independent events.

Definition Independent Events

If two events, \(A\) and \(B\), are independent, the probability that both events happen (that is, \(P(A\cap B)\) or \(P(A \text{ and } B)\)) is the product of their individual probabilities. This is called the multiplication rule for independent events:$$P(A \text{ and } B) = P(A) \times P(B)$$

Example

An experiment consists of the following two independent actions:

- Tossing a fair coin.

- Rolling a fair six-sided die.

Let \(T\) be the event “getting tails” and \(N\) be the event “rolling a number greater than 4”.

- The events are independent, so we can use the multiplication rule.

- The probability of getting tails is \(P(T) = \dfrac{1}{2}\).

- The outcomes for a number greater than 4 are \(\{5, 6\}\). There are 2 favourable outcomes out of 6 total outcomes. So, \(P(N) = \dfrac{2}{6} = \dfrac{1}{3}\).

- Now, we multiply the probabilities to find the probability of both events happening:$$\begin{aligned}P(T \text{ and } N) &= P(T) \times P(N) \\ &= \dfrac{1}{2} \times \dfrac{1}{3} \\ &= \dfrac{1}{6}\end{aligned}$$

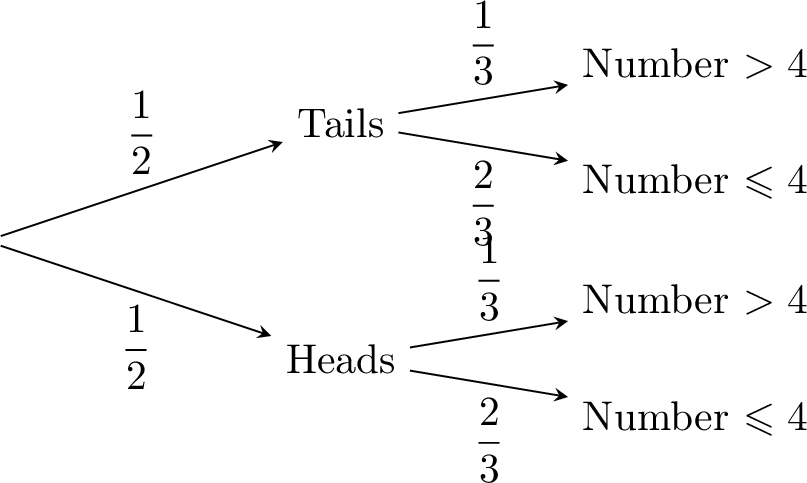

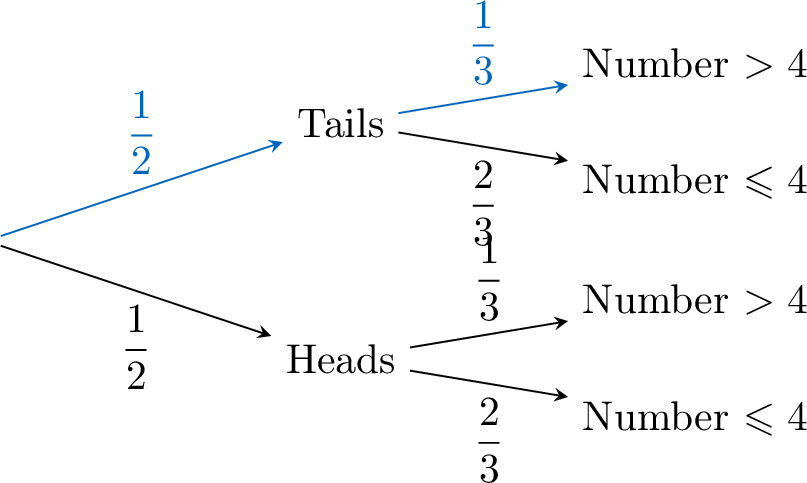

Method Using a Probability Tree Diagram

- Draw branches for each step: Draw branches for the first event (coin toss) and then, from the end of each of those branches, draw the branches for the second event (die roll).

- Write probabilities on each branch: The probabilities on the branches from a single point must add up to 1. Because the events are independent, the probabilities on the die-roll branches are the same after “Tails” and after “Heads”.

- Multiply along the path: To find the probability of a combined event, multiply the probabilities along the path from start to finish.

$$\textcolor{colorprop}{P(\text{"Tails" and "Number > 4"})=\frac{1}{2}\times \frac{1}{3}}$$

$$\textcolor{colorprop}{P(\text{"Tails" and "Number > 4"})=\frac{1}{2}\times \frac{1}{3}}$$

Experimental Probability

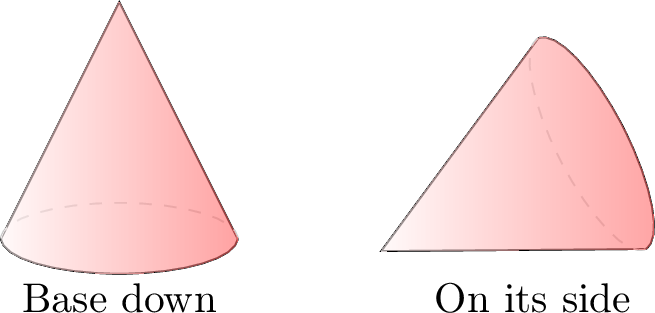

Isaac wants to find the probability that a cone he drops will land on its base. The possible outcomes are “base down” or “on its side”.

- Base down: 15 times.

- On its side: 35 times.

Definition Experimental Probability (Relative Frequency)

The experimental probability of an event is an estimate found by repeating an experiment many times. It is calculated with the formula:$$ \text{Experimental Probability} = \frac{\text{Number of times an event occurs}}{\text{Total number of trials}} $$The more trials we do, the better our estimate of the true probability will be.

Conditional Probability

Imagine you're trying to predict the chance of rain today. You might start with a basic probability based on the weather forecast. But then you notice dark clouds rolling in—suddenly, the odds of rain feel higher because you have new information. This is where conditional probability comes in: it’s about updating probabilities when you know something extra has happened.

Think of it like a game with a bag of colored balls—say, 5 red, 3 blue, and 2 green (10 total). The chance of picking a red ball is 5 out of 10, or \(\frac{5}{10} = \frac{1}{2}\). Now, suppose someone tells you they’ve already removed all the blue balls. The bag now has 5 red and 2 green (7 total), so the chance of picking a red ball jumps to \(\frac{5}{7}\). That’s conditional probability: the probability of an event (picking red) given that another event (blue balls removed) has occurred.

Formally, conditional probability is the likelihood of one event, say \(F\), happening given that another event, \(E\), has already taken place. We write it as \(\PCond{F}{E}\), pronounced “the probability of \(F\) given \(E\).” It’s a way to refine our predictions with new context, and it’s used everywhere—from weather forecasts to medical tests.

Think of it like a game with a bag of colored balls—say, 5 red, 3 blue, and 2 green (10 total). The chance of picking a red ball is 5 out of 10, or \(\frac{5}{10} = \frac{1}{2}\). Now, suppose someone tells you they’ve already removed all the blue balls. The bag now has 5 red and 2 green (7 total), so the chance of picking a red ball jumps to \(\frac{5}{7}\). That’s conditional probability: the probability of an event (picking red) given that another event (blue balls removed) has occurred.

Formally, conditional probability is the likelihood of one event, say \(F\), happening given that another event, \(E\), has already taken place. We write it as \(\PCond{F}{E}\), pronounced “the probability of \(F\) given \(E\).” It’s a way to refine our predictions with new context, and it’s used everywhere—from weather forecasts to medical tests.

Definition

Let’s explore conditional probability with a two-way table showing 100 students’ preferences for math, split by gender:

| Loves Math | Does Not Love Math | Total | |

| Girls | 35 | 16 | 51 |

| Boys | 30 | 19 | 49 |

| Total | 65 | 35 | 100 |

- Probability the student is a girl:$$\begin{aligned}P(\text{Girl}) &= \frac{\text{Number of girls}}{\text{Number of students}} \\ &= \frac{51}{100}.\end{aligned}$$

- Probability the student loves math and is a girl:$$\begin{aligned}P(\text{Loves Math and Girl}) &= \frac{\text{Number of girls who love math}}{\text{Number of students}} \\ &= \frac{35}{100}.\end{aligned}$$

- Probability the student loves math, given they are a girl:

Since we’re told the student is a girl, we focus only on the 51 girls:$$\begin{aligned}\PCond{\text{Loves Math}}{\text{Girl}} &= \frac{\text{Number of girls who love math}}{\text{Number of girls}} \\ &= \frac{35}{51}.\end{aligned}$$ - Connecting to the formula:

Notice that:$$\begin{aligned}\PCond{\text{Loves Math}}{\text{Girl}} &=\frac{35}{51}\\ &= \frac{35/100}{51/100}\\ &= \dfrac{P(\text{Loves Math and Girl})}{P(\text{Girl})}.\end{aligned}$$This pattern gives us the general rule for conditional probability.

Definition Conditional Probability

The conditional probability of event \(F\) given event \(E\) is the probability of \(F\) occurring, knowing that \(E\) has already happened. It’s denoted \(\PCond{F}{E}\) and calculated as:$$\textcolor{colordef}{\PCond{F}{E} = \frac{P(E \cap F)}{P(E)}}, \quad \text{where } P(E) > 0.$$

Example

A fair six-sided die has odd faces (1, 3, 5) painted green and even faces (2, 4, 6) painted blue. You roll it and see the top face is blue. What’s the probability it’s a 6?

- Sample space: \(\{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6\}\), 6 equally likely outcomes.

- Event \(E\) (face is blue): \(\{2, 4, 6\}\), so \(P(E) = \frac{3}{6}\).

- Event \(F\) (roll a 6): \(\{6\}\).

- Intersection \(E \cap F\): \(\{6\}\), so \(P(E \cap F) = \frac{1}{6}\).

- Conditional probability:$$\begin{aligned}\PCond{F}{E} &= \frac{P(E \cap F)}{P(E)}\\ &= \frac{\frac{1}{6}}{\frac{3}{6}}\\ &= \frac{1}{6} \times \frac{6}{3}\\ &= \frac{1}{3}.\end{aligned}$$

- The probability of rolling a 6, given the face is blue, is \(\frac{1}{3}\).

Conditional Probability Tree Diagrams

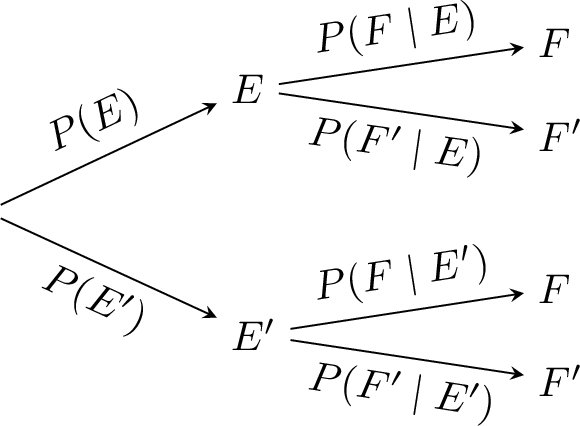

Definition Conditional Probability Tree Diagram

A conditional probability tree visually organizes probabilities for a sequence of events:

- Each branch from a node shows either an unconditional probability (e.g. \(P(E)\)) or a conditional probability (e.g. \(\PCond{F}{E}\)).

- Events are labeled at the end of each branch.

- The probability of an outcome at the end of a path is the product of the probabilities along that path.

Example

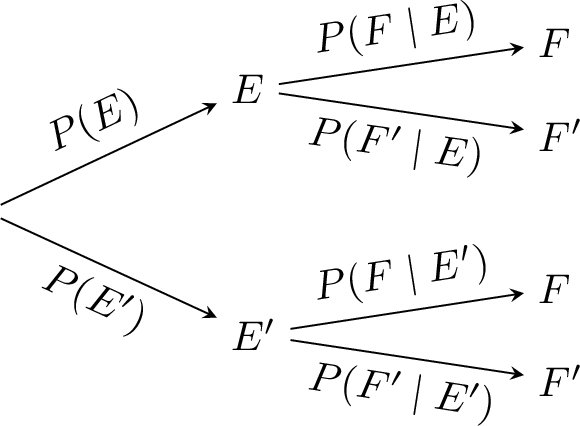

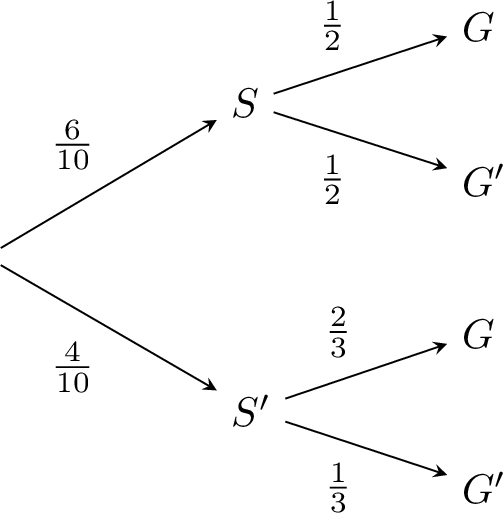

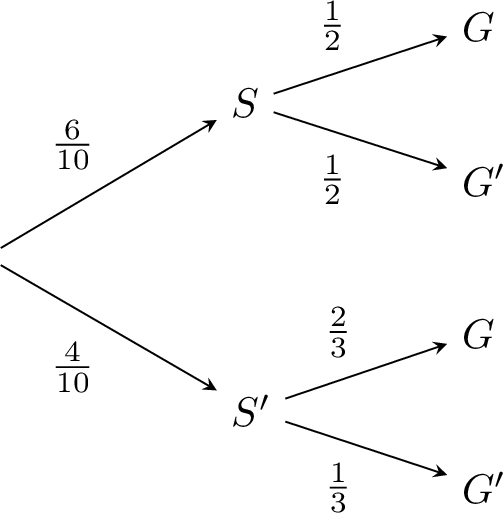

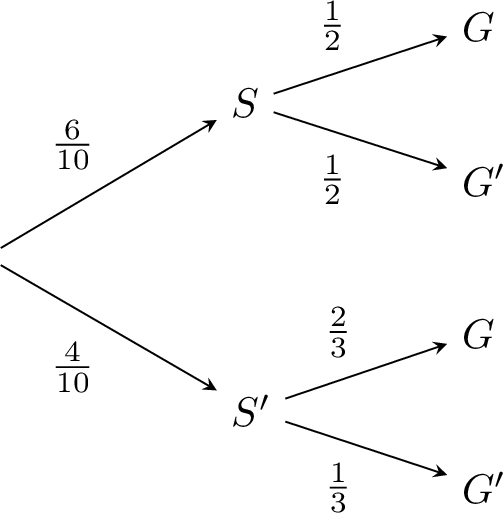

The probability Sam coaches a game is \(\frac{6}{10}\), and the probability Alex coaches is \(\frac{4}{10}\). If Sam coaches, the probability that a randomly selected player is a goalkeeper is \(\frac{1}{2}\); if Alex coaches, it is \(\frac{2}{3}\).

Draw the tree diagram.

Draw the tree diagram.

- Define the events:

- \(S\): Sam coaches.

- \(G\): Player is goalkeeper.

- Define the probabilities:

- \(P(S) = \frac{6}{10}\) and \(P(S') =1 - P(S)= \frac{4}{10}\).

- \(\PCond{G}{S} = \frac{1}{2}\) and \(\PCond{G'}{S} = 1 - \PCond{G}{S} = \frac{1}{2}\).

- \(\PCond{G}{S'} = \frac{2}{3}\) and \(\PCond{G'}{S'} = 1-\PCond{G}{S'}= \frac{1}{3}\).

- Tree diagram:

Joint Probability: \(P(E \cap F)\)

Sometimes we know \(P(E)\) and \(\PCond{F}{E}\) and need the chance both \(E\) and \(F\) happen together—like finding the probability that a student is a girl who loves math. This probability is called the joint probability \(P(E \cap F)\).

Proposition Joint Probability Formula

$$P(E \cap F) = P(E) \times \PCond{F}{E}, \quad P(E \cap F) = P(F) \times \PCond{E}{F}.$$

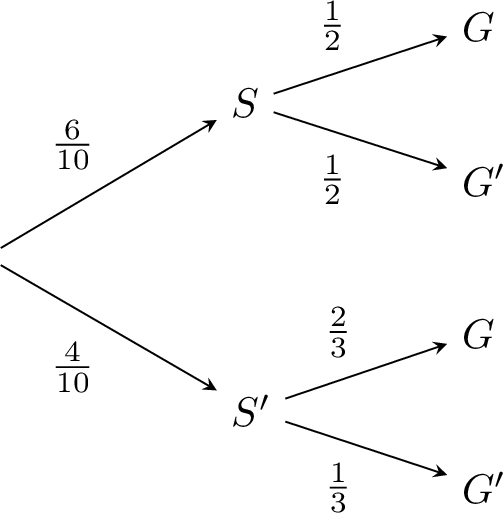

Method Finding \(P(E \cap F)\) in a Tree

- Identify the path where \(E\) and \(F\) both occur.

- Multiply the probabilities along that path.

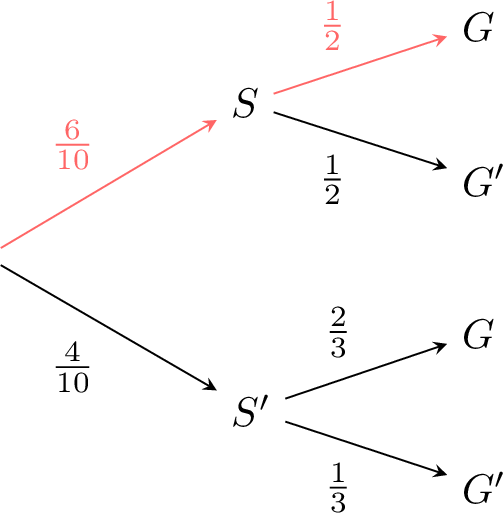

Example

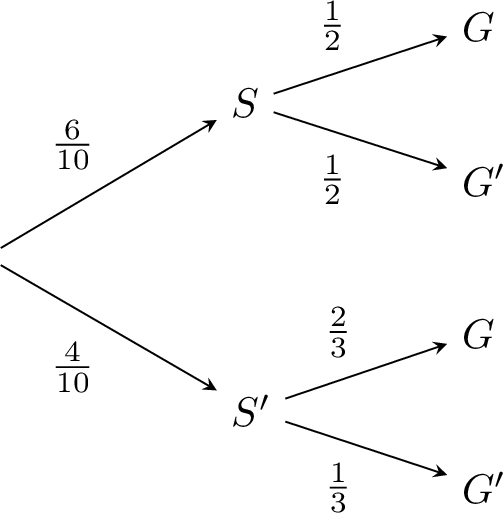

For this probability tree,

- Path: \(S\) to \(G\) (highlighted):

- Calculate:$$\begin{aligned}P(S \cap G) &= P(S) \times \PCond{G}{S}\\ &= \frac{6}{10} \times \frac{1}{2}\\ &= \frac{3}{10}.\end{aligned}$$

Law of Total Probability

Theorem Law of Total Probability

For events \(E\) and \(F\):$$P(F) = P(E) \PCond{F}{E} + P(E') \PCond{F}{E'}.$$This applies when \(E\) and its complement \(E'\) form a partition of the sample space. More generally, if \((E_1,\dots,E_n)\) is a partition of the sample space, then$$P(F) = \sum_{i=1}^n P(E_i)\PCond{F}{E_i}.$$

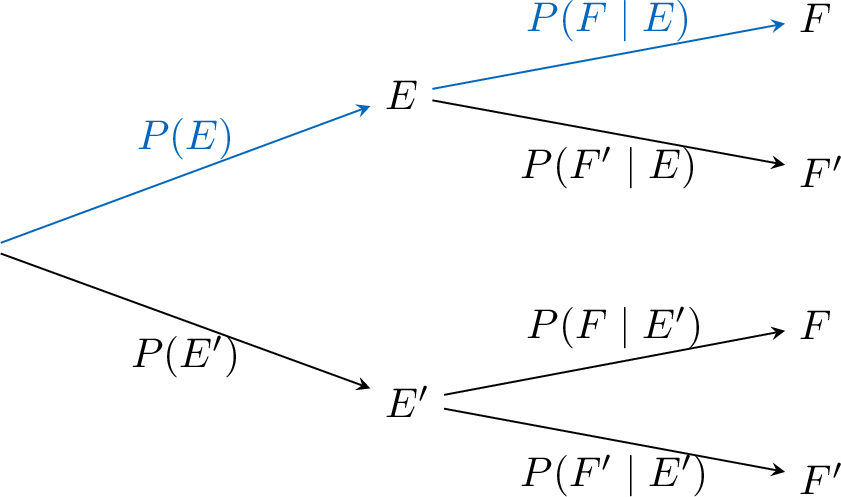

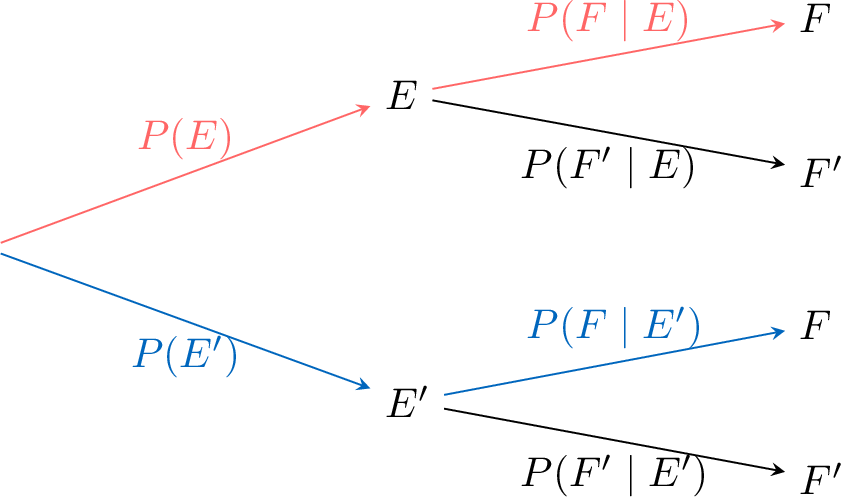

Method Finding \(P(F)\) in a Tree

- Identify all paths to \(F\).

- Multiply probabilities along each path and sum them.

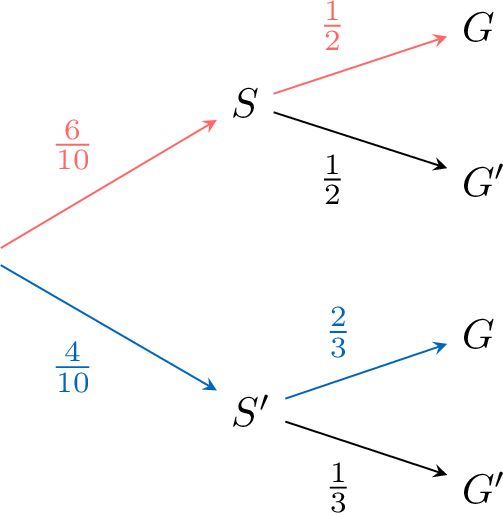

Example

For this probability tree,

- Paths to \(G\):

- Calculate:$$\begin{aligned}P(G) &= \textcolor{colordef}{\frac{6}{10} \times \frac{1}{2}} + \textcolor{colorprop}{\frac{4}{10} \times \frac{2}{3}} \\ &= \textcolor{colordef}{\frac{3}{10}} + \textcolor{colorprop}{\frac{8}{30}} \\ &= \textcolor{colordef}{\frac{9}{30}} + \textcolor{colorprop}{\frac{8}{30}} \\ &= \frac{17}{30}.\end{aligned}$$