Reasoning and Proof

Mathematical progress has always been driven by formal methods of proof. While science often relies on experimental evidence, mathematics is built upon the certainty of logical deduction from clearly stated assumptions. A mathematical proof is a rigorous argument that establishes the truth of a statement from agreed axioms and previously proven results. It begins with assumptions called hypotheses, proceeds through a sequence of justified logical steps, and arrives at a conclusion. This chapter introduces the fundamental language of mathematical logic and explores the primary methods of proof required in this course.

Logical Connectives and Propositions

Proposition

Definition Proposition and Truth Value

A proposition is a declarative statement that has a definite truth value: it is either true or false (but not both). We typically denote propositions by letters such as \(p,q,r\).

Note

Unless stated otherwise, any proposition or theorem presented in a mathematical text is asserted to be true. The goal of a proof is to demonstrate this truth.

Example

- \(p\): "The number 9 is a prime number." (False)

- \(q\): "3 is a divisor of 12." (True)

Negation

Definition Negation

The negation of a proposition \(p\), denoted \(\neg p\), is the proposition "not \(p\)". The truth value of \(\neg p\) is the opposite of the truth value of \(p\).

Example

\(p\): "The integer \(4\) is an even number." (True)

\(\neg p\): "The integer \(4\) is not an even number." (False)

\(\neg p\): "The integer \(4\) is not an even number." (False)

Compound Propositions

Definition Conjunction

The conjunction of \(p\) and \(q\), denoted \(\boldsymbol{p \wedge q}\), is the proposition "\(p\) and \(q\)". It is true only when both \(p\) and \(q\) are true.

Example

Let \(p\): "\(n\) is a multiple of \(2\)" and \(q\): "\(n\) is a multiple of \(3\)".

The conjunction \(p \wedge q\) is "\(n\) is a multiple of \(2\) and \(n\) is a multiple of \(3\)",which means that \(n\) is a multiple of both \(2\) and \(3\) (for example, \(n = 6, 12, 18, \dots\)).

The conjunction \(p \wedge q\) is "\(n\) is a multiple of \(2\) and \(n\) is a multiple of \(3\)",which means that \(n\) is a multiple of both \(2\) and \(3\) (for example, \(n = 6, 12, 18, \dots\)).

Definition Disjunction

The disjunction of \(p\) and \(q\), denoted \(\boldsymbol{p \vee q}\), is the proposition "\(p\) or \(q\)". It is true if at least one of \(p\) or \(q\) is true. This is an inclusive or.

Example

Let \(p\): "\(n\) is a multiple of 2" and \(q\): "\(n\) is a multiple of \(3\)".

The disjunction \(p \vee q\) is true if \(n\) is a multiple of 2, or a multiple of 3, or both (e.g., for \(n=2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, \dots\)).

The disjunction \(p \vee q\) is true if \(n\) is a multiple of 2, or a multiple of 3, or both (e.g., for \(n=2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, \dots\)).

Proposition De Morgan's Laws

The negation of a conjunction or a disjunction follows a specific pattern known as De Morgan's Laws.

- Negation of a Conjunction: \(\boldsymbol{\neg(p \wedge q) \Leftrightarrow (\neg p \vee \neg q)}\)

To negate an "and" statement, you negate each part and change the "and" to an "or". - Negation of a Disjunction: \(\boldsymbol{\neg(p \vee q) \Leftrightarrow (\neg p \wedge \neg q)}\)

To negate an "or" statement, you negate each part and change the "or" to an "and".

Example

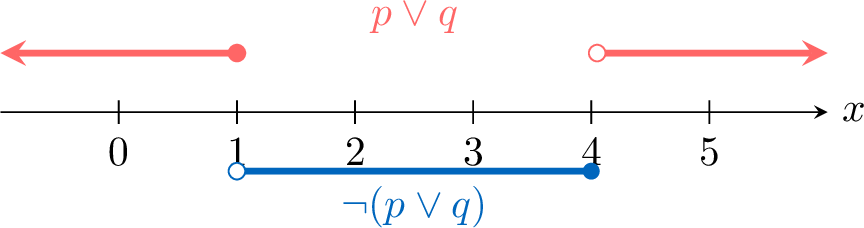

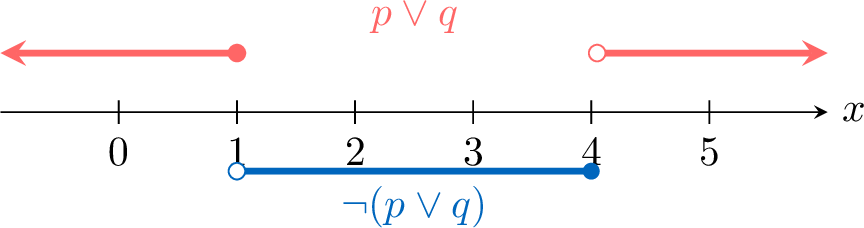

Find the negation of the statement "\(x \le 1\) or \(x > 4\)".

Let \(p\) be "\(x \le 1\)" and \(q\) be "\(x > 4\)". The statement is a disjunction, \(p \vee q\). We use the second of De Morgan's Laws: \(\neg(p \vee q) \Leftrightarrow (\neg p \wedge \neg q)\).First, we find the negation of each part:

- The negation of \(p: x \le 1\) is \(\neg p: x > 1\).

- The negation of \(q: x > 4\) is \(\neg q: x \le 4\).

Implication and Equivalence

Implications capture deduction: from \(p\) we may conclude \(q\). If \(p\Rightarrow q\) and \(p\) is true, then \(q\) must be true.

Definition Implication

An implication, denoted \(\boldsymbol{p \Rightarrow q}\), is the proposition "if \(p\), then \(q\)". It is false only when \(p\) is true and \(q\) is false.

Definition Converse, Inverse, Contrapositive

For the implication \(p \Rightarrow q\):

- The converse is \(q \Rightarrow p\).

- The contrapositive is \(\neg q \Rightarrow \neg p\).

- The inverse is \(\neg p \Rightarrow \neg q\).

Example

"If \(x=1\) then \(x^2=1\)" is true. The converse "If \(x^2=1\) then \(x=1\)" is false (since \(x=-1\) also satisfies \(x^2=1\)).

Definition Equivalence

An equivalence, denoted \(\boldsymbol{p \Leftrightarrow q}\), is the proposition "\(p\) if and only if \(q\)". It is true only when \(p\) and \(q\) have the same truth value. It is the conjunction of an implication and its converse: \((p \Rightarrow q) \wedge (q \Rightarrow p)\).

Proposition Contrapositive Equivalence

An implication and its contrapositive are logically equivalent: \(\boldsymbol{(p \Rightarrow q) \Leftrightarrow (\neg q \Rightarrow \neg p)}\).

Assume that the implication “If it is raining, then the ground is wet.” is true. Because an implication and its contrapositive are logically equivalent, we can deduce that the contrapositive is also true:

- Implication: “If it is raining, then the ground is wet.”

- Contrapositive: “If the ground is not wet, then it is not raining.”

Quantifiers

Definition Quantifiers

- The universal quantifier \(\forall\) means “for all”. “\(\forall x\in S,\;P(x)\)” asserts that \(P(x)\) holds for every \(x\in S\).

- The existential quantifier \(\exists\) means “there exists”. “\(\exists x\in S,\;P(x)\)” asserts that there is at least one \(x\in S\) for which \(P(x)\) holds.

Example

Let \(S = \{1, 2, 3\}\).

- \(\forall x \in S, x < 4\) is a true statement, since \(1<4\), \(2<4\) and \(3<4\).

- \(\exists x \in S, x \text{ is even}\) is a true statement, since \(2\) is even.

- \(\forall x \in S, x \text{ is odd}\) is a false statement, since \(2\) is not odd.

Proposition Negation of Quantifiers

- The negation of "\(\forall x \in S, P(x)\)" is "\(\exists x \in S, \neg P(x)\)".

- The negation of "\(\exists x \in S, P(x)\)" is "\(\forall x \in S, \neg P(x)\)".

Example

The negation of the statement “All integers are even”$$\forall n \in \mathbb{Z},\; n \text{ is even}$$is “There exists at least one integer that is odd”$$\exists n \in \mathbb{Z},\; \neg(n \text{ is even}) \quad\text{that is,}\quad \exists n \in \mathbb{Z},\; n \text{ is odd}.$$

Written Proof

Structure for Written Proofs

Method Structure for Written Proofs

A clear, well-structured proof generally follows these steps:

- Statement: Clearly state the proposition you intend to prove and, if relevant, the method you will use.

- Assumptions: Explicitly state your initial hypotheses. For direct proofs, this means assuming the premise \(p\) of the implication \(p \Rightarrow q\).

- Logical Steps: Present a sequence of clear, logical deductions, justifying each step with definitions, axioms, or previously proven theorems.

- Conclusion: State the final conclusion, explicitly linking it back to the original proposition.

Example

Direct proof: the sum of two even integers is even.

- Claim:

We prove by direct proof: if \(a,b\) are even integers, then \(a+b\) is even. - Assumptions:

Let \(a,b\) be two even integers. By definition of even numbers, there exist \(k,\ell\in\Z\) such that$$ a=2k \quad\text{and}\quad b=2\ell. $$ - Logical Steps:

$$\begin{aligned}a+b &= 2k + 2\ell \\ &= 2(k+\ell).\end{aligned}$$Since \(k+\ell\in\Z\), the sum \(a+b\) is a multiple of \(2\). - Conclusion:

By definition of even numbers, \(a+b\) is even.

Method Advice for Writing Proofs

- Write down the hypotheses and the desired conclusion first; they guide your route. It can help to work backward from the conclusion on scratch paper.

Proof in progress: the left “hand” is the hypothesis, the right “hand” the conclusion—meet in the middle. - Use a draft. Explore freely on scratch paper before composing the final, clean argument.

The great mathematician Maryam Mirzakhani working intently on a draft. - Iterate. Get feedback, revise, and don’t expect a perfect proof on the first try.

Feedback loop with Dr. Tariel and a CommeUnJeu Academy student.

Introducing a Variable

To reason about all elements of a set \(E\), introduce a generic element with “Let \(x\in E\).” It then stands for an arbitrary element throughout the proof.

Method Introduce a Variable

Let \(x\in E\).

\(\vdots\quad\quad \quad\quad\) (reason about \(x\))

Therefore, the statement holds for all \(x\in E\).

\(\vdots\quad\quad \quad\quad\) (reason about \(x\))

Therefore, the statement holds for all \(x\in E\).

Methods of Proof

Direct Proof (Proof by Deduction)

Method Direct Proof

To prove \(p \Rightarrow q\), a direct proof assumes \(p\) is true and uses a sequence of logical deductions to show that \(q\) must also be true.$$\begin{aligned}&\text{Assume } p \text{ is true.} && (\text{Hypothesis})\\

&\quad\vdots\quad && (\text{Logical steps})\\

&\text{So, } q \text{ is true.}&& (\text{Conclusion}).\end{aligned}$$

Example

Prove that if an integer \(a\) divides both integers \(b\) and \(c\), then \(a\) divides their sum \(b+c\).

Let \(a, b,\) and \(c\) be integers.

Suppose that \(a\) divides \(b\) and \(a\) divides \(c\).

By the definition of divisibility, there exist integers \(k\) and \(m\) such that$$ b = ak \quad \text{and} \quad c = am. $$Now, consider the sum \(b+c\):$$\begin{aligned}b + c &= ak + am \\ &= a(k+m).\end{aligned}$$By definition, this means that \(a\) divides \(b+c\).

Suppose that \(a\) divides \(b\) and \(a\) divides \(c\).

By the definition of divisibility, there exist integers \(k\) and \(m\) such that$$ b = ak \quad \text{and} \quad c = am. $$Now, consider the sum \(b+c\):$$\begin{aligned}b + c &= ak + am \\ &= a(k+m).\end{aligned}$$By definition, this means that \(a\) divides \(b+c\).

Proof by Contrapositive

Method Proof by Contrapositive

To prove the implication \(p \Rightarrow q\), we can instead prove its logically equivalent contrapositive, \(\neg q \Rightarrow \neg p\).$$\begin{aligned} &\text{Assume } \neg q \text{ is true.} && (\text{Hypothesis})\\

&\quad\vdots\quad && (\text{Logical steps})\\

&\text{Therefore, } \neg p \text{ is true.}&& (\text{Conclusion}).\end{aligned}$$

Example

Prove that if \(a^2\) is even, then \(a\) is even.

We will prove the contrapositive: "If \(a\) is odd, then \(a^2\) is odd."

Assume \(a\) is an odd integer.

Then there exists an integer \(k\) such that \(a=2k+1\).$$\begin{aligned} a^2 &= (2k+1)^2\\ &= 4k^2+4k+1\\ &= 2(2k^2+2k)+1.\end{aligned}$$So \(a^2\) is of the form \(2m+1\) and is therefore odd.

Since we have proved the contrapositive, the original statement is true.

Assume \(a\) is an odd integer.

Then there exists an integer \(k\) such that \(a=2k+1\).$$\begin{aligned} a^2 &= (2k+1)^2\\ &= 4k^2+4k+1\\ &= 2(2k^2+2k)+1.\end{aligned}$$So \(a^2\) is of the form \(2m+1\) and is therefore odd.

Since we have proved the contrapositive, the original statement is true.

Proof by Exhaustion (Cases)

A proof by exhaustion involves breaking down a statement into a finite number of distinct cases and proving that the statement holds true for every one of those cases. It is crucial to demonstrate that the chosen cases cover all possibilities.

Method Proof by Exhaustion (Cases)

To prove a proposition \(P\), identify a finite set of cases \(\{C_1, C_2, \dots, C_n\}\) that are exhaustive (cover all possibilities).

- Prove that \(P\) is true for Case \(C_1\).

- Prove that \(P\) is true for Case \(C_2\).

- ...

- Prove that \(P\) is true for Case \(C_n\).

Example

Prove that for any integer \(n\), \(n(n+1)\) is even.

Let \(n\) be any integer.

- Case 1: \(n\) is even.

There exists an integer \(k\) such that \(n=2k\). $$ \begin{aligned} n(n+1) &= 2k(2k+1)\\ &= 2[k(2k+1)]. \end{aligned} $$ So \(n(n+1)\) is even. - Case 2: \(n\) is odd.

There exists an integer \(k\) such that \(n=2k+1\). $$ \begin{aligned} n(n+1) &= (2k+1)((2k+1)+1)\\ &= (2k+1)(2k+2)\\ &= 2\left[(2k+1)(k+1)\right]. \end{aligned} $$ So \(n(n+1)\) is even.

Disproof by Counterexample

To prove that a universal statement is false, one only needs to find a single case for which it does not hold. For example, to prove the statement "All students in my class are boys" is false, I only need to find one student who is a girl. In logical notation, saying that “\(\forall x\in E,\;P(x)\)” is false is equivalent to saying that “\(\exists x\in E,\;\neg P(x)\)” is true.

Method Disproof by Counterexample

To disprove the statement "\(\forall x\in E,\;P(x)\)", it is sufficient to find one element \(c \in E\) for which \(P(c)\) is false. This element \(c\) is called a counterexample. In other words, we show that the existential statement "\(\exists x\in E,\;\neg P(x)\)" is true.

Example

Disprove “All odd numbers are prime numbers.”

Counterexample: \(9\) is odd but not prime (since \(9 = 3 \times 3\)).

Proof by Equivalence

To prove \(p\Leftrightarrow q\), either prove both directions (\(p\Rightarrow q\) and \(q\Rightarrow p\)) or transform \(p\) step by step into \(q\) using known equivalences.

Method Proof by Equivalence

To prove \(p \Leftrightarrow q\), two methods are possible:

- Double Implication:

- Prove the forward direction: Assume \(p\) is true and show that \(q\) must be true (\(p \Rightarrow q\)).

- Prove the reverse direction: Assume \(q\) is true and show that \(p\) must be true (\(q \Rightarrow p\)).

- Chain of Equivalences: Start with statement \(p\) and construct a sequence of logically equivalent statements that ends with \(q\). $$ p \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad s_1 \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad s_2 \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad \dots \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad q. $$

Example

For \(n\in\Z\), the following statements are equivalent:$$n \text{ is even} \;\Leftrightarrow\; n^2 \text{ is even}.$$

- (\(\Rightarrow\)) Suppose \(n\) is even. Then there exists \(k\in\Z\) such that \(n = 2k\). Hence$$n^2 = (2k)^2 = 4k^2 = 2(2k^2),$$so \(n^2\) is even.

- (\(\Leftarrow\)) Suppose \(n^2\) is even. By the result proved earlier (“If \(a^2\) is even, then \(a\) is even”), it follows that \(n\) is even.

Proof by Contradiction

Proof by contradiction is based on the idea that if an assumption leads to a logical absurdity, the assumption must be false (e.g. \(1=0\)). The logical form can be summarised as: if assuming \(\neg p\) leads to a contradiction, then \(p\) must be true.

Method Proof by Contradiction

To prove a proposition \(p\) is true by contradiction:$$\begin{aligned} &\text{Assume } \neg p \text{ is true.} && (\text{Hypothesis})\\

&\quad\vdots\quad && (\text{Logical steps leading to a contradiction, e.g. } 1=0)\\

&\text{Contradiction! Therefore, the assumption } \neg p \text{ is false.} && \\

&\text{Thus, } p \text{ must be true.}&& (\text{Conclusion}).\end{aligned}$$

Example

Prove by contradiction that the number of prime numbers is infinite.

Suppose there are only a finite number \(n\) of prime numbers, which we label \(p_1, p_2, \dots, p_n\).

Every positive integer greater than 1 is either a member of this list, or is divisible by a member of this list.

Let \(N = p_1 \times p_2 \times \dots \times p_n + 1\). Notice that:

Every positive integer greater than 1 is either a member of this list, or is divisible by a member of this list.

Let \(N = p_1 \times p_2 \times \dots \times p_n + 1\). Notice that:

- \(N > p_k\) for all \(k=1, \dots, n\).

So, \(N\) is not a member of the list. - If we divide \(N\) by any \(p_k\), \(k=1, \dots, n\), then the remainder is \(1\).

So, \(N\) is not divisible by any \(p_k\).

Proof by Mathematical Induction

Proof by induction is a powerful technique used to prove that a proposition \(P(n)\) is true for all integers \(n\) above a certain starting value. It is analogous to knocking over a line of dominoes: if you can knock over the first one, and you know that each domino will knock over the next, then all dominoes will eventually fall.

Method The Principle of Mathematical Induction

To prove by induction that a proposition \(P(n)\) is true for all integers \(n \ge n_0\):

- Base Case (Initialisation): Prove that \(P(n_0)\) is true.

- Inductive Step (Hérédité):

- Assume \(P(k)\) is true for an arbitrary integer \(k \ge n_0\) (this is the inductive hypothesis).

- Using this assumption, prove that \(P(k+1)\) must also be true.

Example

Prove by mathematical induction that for all integers \(n \ge 1\),$$1 + 2 + 3 + \dots + n = \frac{n(n+1)}{2}.$$

Let \(P(n)\) be the proposition$$P(n): \quad 1 + 2 + 3 + \dots + n = \frac{n(n+1)}{2}$$for integers \(n \ge 1\).

- Base case \(n=1\):\$$0.2em]On the left-hand side, we have \(1\). On the right-hand side,$$\frac{1(1+1)}{2} = \frac{2}{2} = 1.$$So \(P(1)\) is true.\$$0.4em]

- Inductive step:

Assume \(P(k)\) is true for some integer \(k \ge 1\), that is,$$1 + 2 + 3 + \dots + k = \frac{k(k+1)}{2}.$$We must show that \(P(k+1)\) is true:$$1 + 2 + 3 + \dots + k + (k+1) = \frac{(k+1)(k+2)}{2}.$$Starting from the left-hand side of \(P(k+1)\):$$\begin{aligned}1 + 2 + \dots + k + (k+1)&= \left(1 + 2 + \dots + k\right) + (k+1) \\ &= \frac{k(k+1)}{2} + (k+1) \quad &&\text{(by the inductive hypothesis)}\\ &= \frac{k(k+1)}{2} + \frac{2(k+1)}{2} \\ &= \frac{(k+1)(k+2)}{2}.\end{aligned}$$Thus \(P(k+1)\) is true.