Line Equations

Slopes

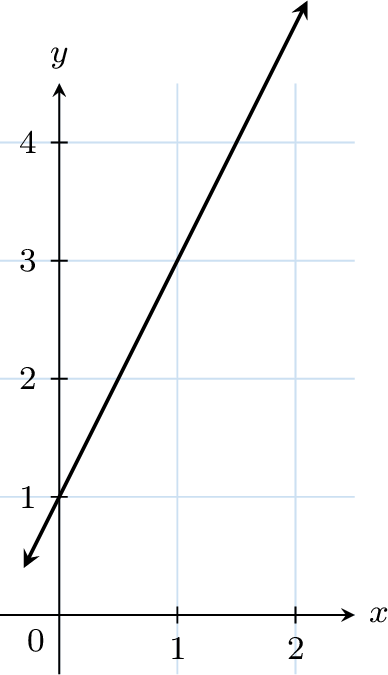

The slope (or gradient) of a line describes its direction and steepness. It is a number that tells us how much the \(y\)-coordinate of a point on the line changes when the \(x\)-coordinate increases by \(1\) unit.

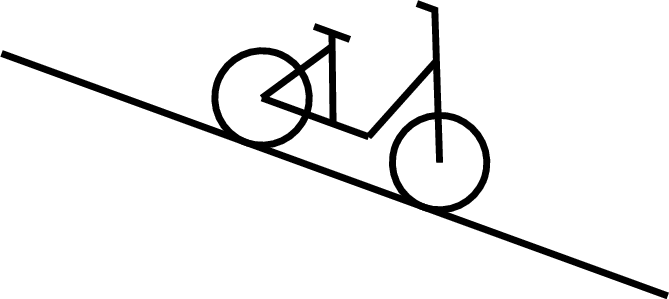

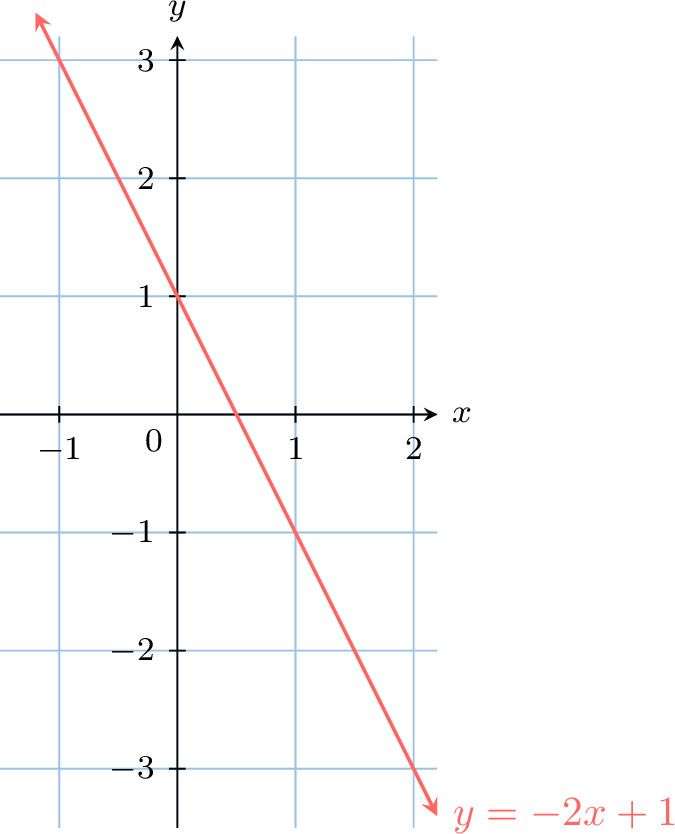

- A positive slope indicates that the line goes up (ascends) as you move to the right.

- A negative slope indicates that the line goes down (descends) as you move to the right.

- A slope of zero means the line is horizontal: as you move to the right, there is no vertical change.

Definition Slope

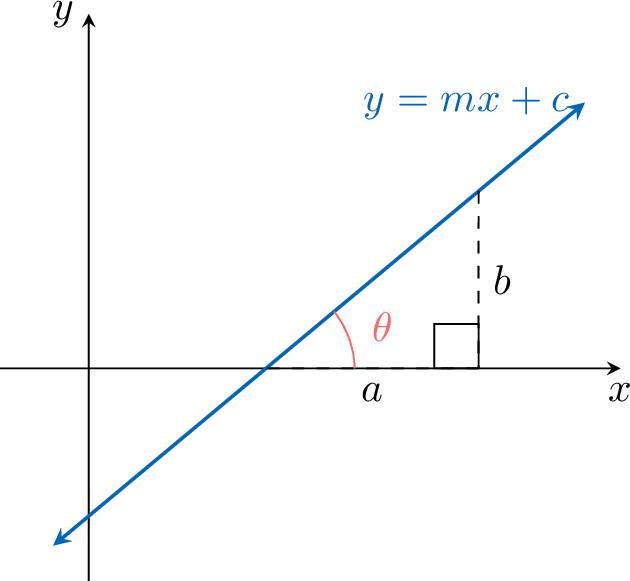

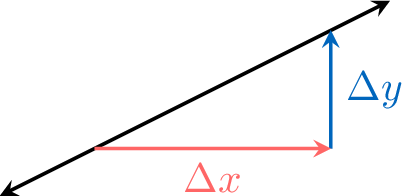

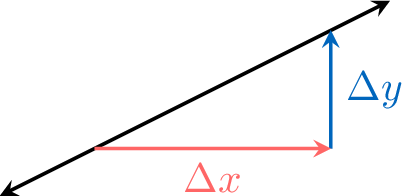

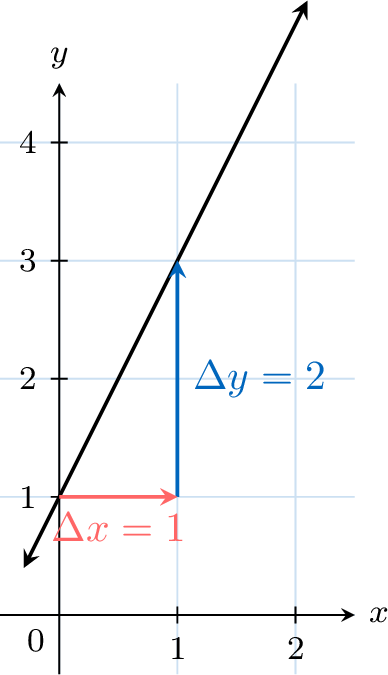

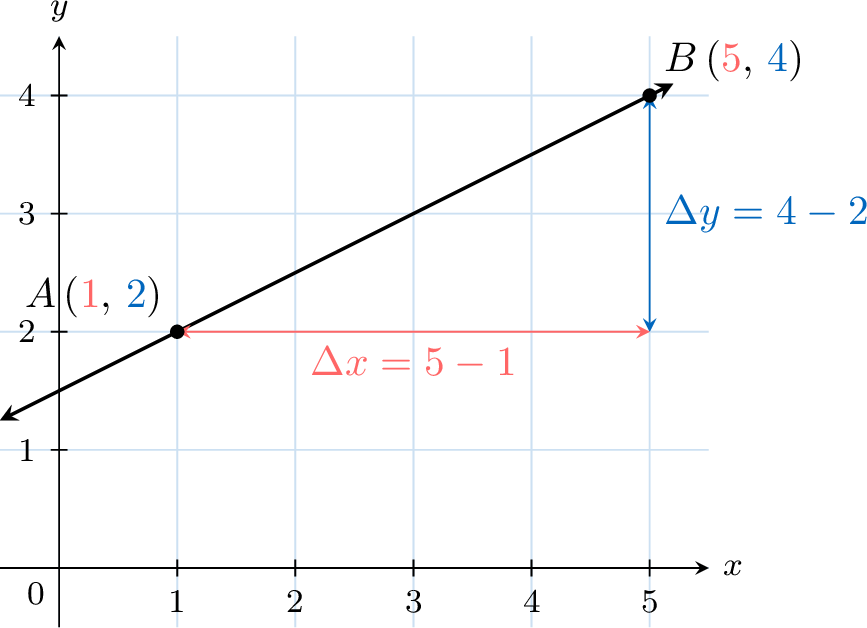

The slope (or gradient) of a non-vertical line is defined as the ratio of the change in the vertical direction (\(\Delta y\)) to the change in the horizontal direction (\(\Delta x\)), for any two distinct points on the line. This ratio is the same no matter which two points on the line we choose:$$\text{slope} = \dfrac{\textcolor{colorprop}{\Delta y}}{\textcolor{colordef}{\Delta x}} = \dfrac{\textcolor{colorprop}{\text{vertical change}}}{\textcolor{colordef}{\text{horizontal change}}}, \quad \text{where } \textcolor{colordef}{\Delta x} \neq 0$$

Example

Slope Formula

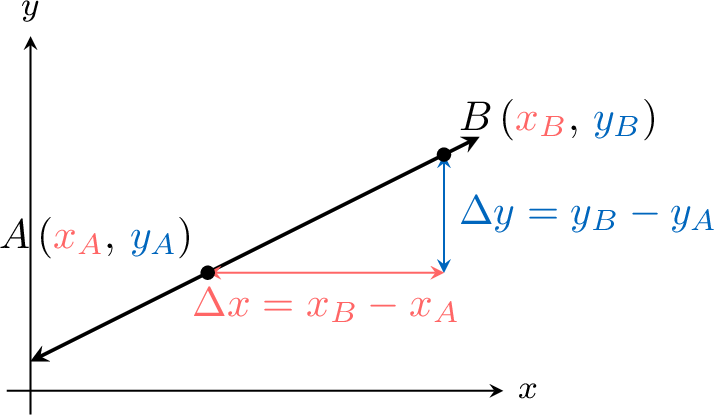

Proposition Slope Formula

The slope of a non-vertical line passing through two distinct points \(A\left(\textcolor{colordef}{x_A}, \textcolor{colorprop}{y_A}\right)\) and \(B\left(\textcolor{colordef}{x_B}, \textcolor{colorprop}{y_B}\right)\) is given by the formula:$$\text{slope} = \frac{\textcolor{colorprop}{y_B}-\textcolor{colorprop}{y_A}}{\textcolor{colordef}{x_B}-\textcolor{colordef}{x_A}}, \quad \text{where } \textcolor{colordef}{x_A} \neq \textcolor{colordef}{x_B}$$The order of the points does not matter, as long as we subtract in the same order in the numerator and the denominator.

Example

Find the slope of the line \(\Line{AB}\) for \(A\left(\textcolor{colordef}{1}, \textcolor{colorprop}{2}\right)\) and \(B\left(\textcolor{colordef}{5}, \textcolor{colorprop}{4}\right)\).

\(y\)-Intercept

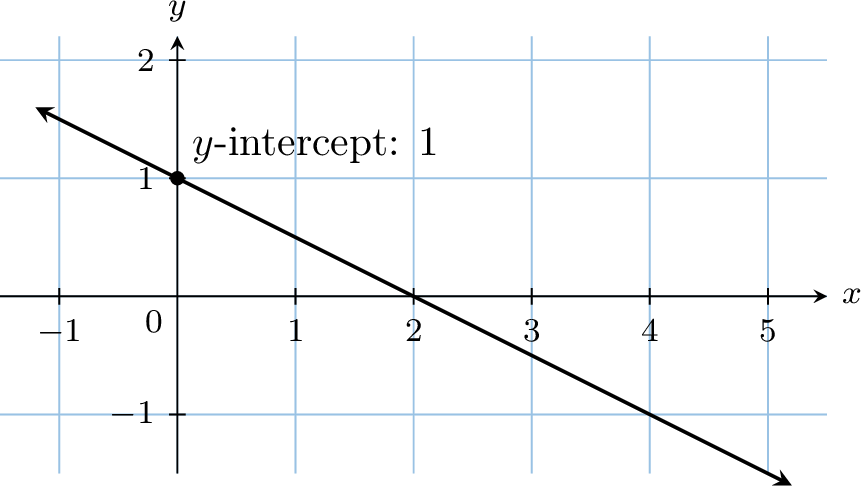

Definition \(y\)-Intercept

The \(y\)-intercept is the value of \(y\) where the graph crosses the \(y\)-axis (when \(x=0\)).

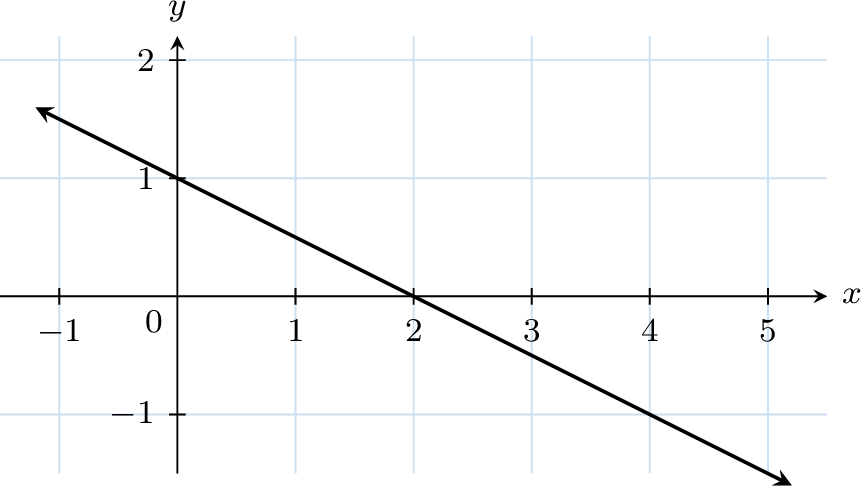

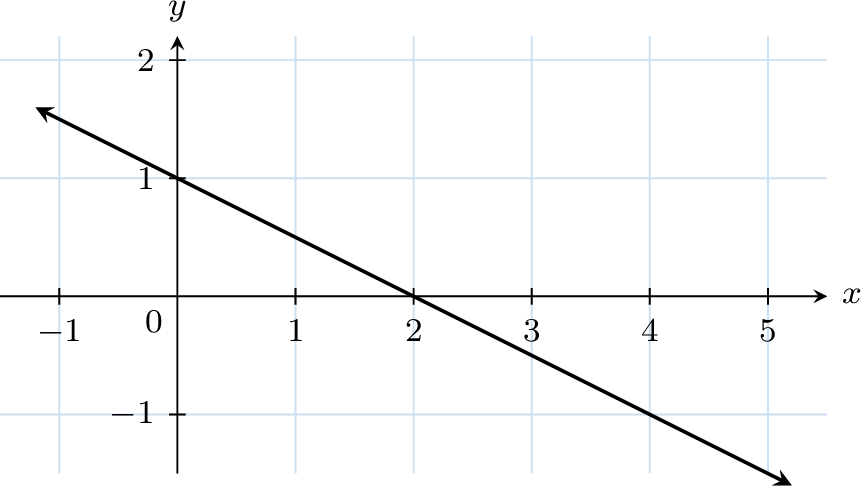

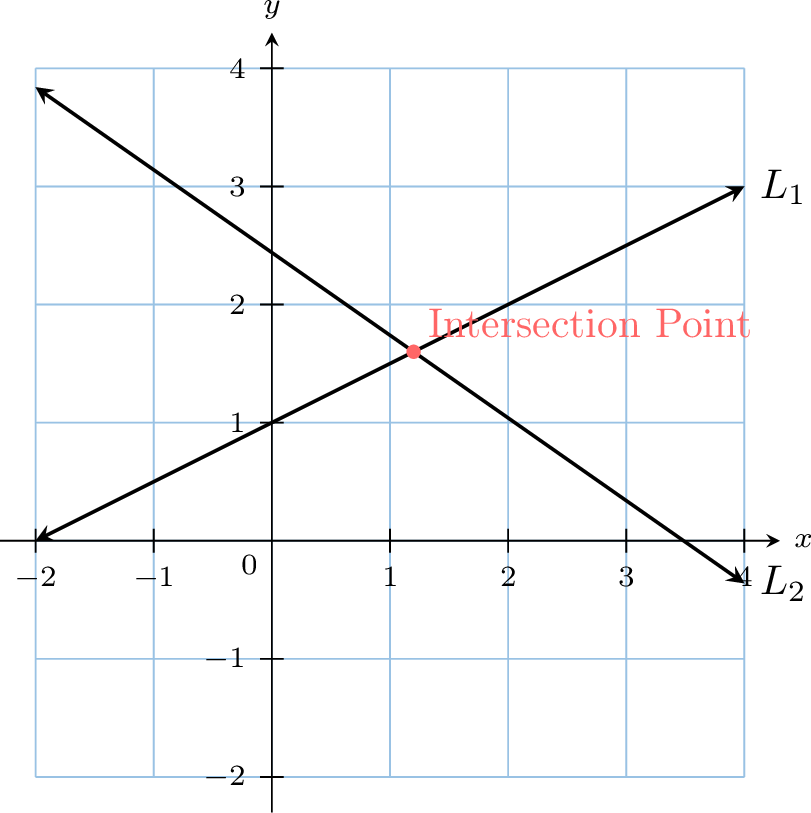

Example

Find the \(y\)-intercept.

Line Equations

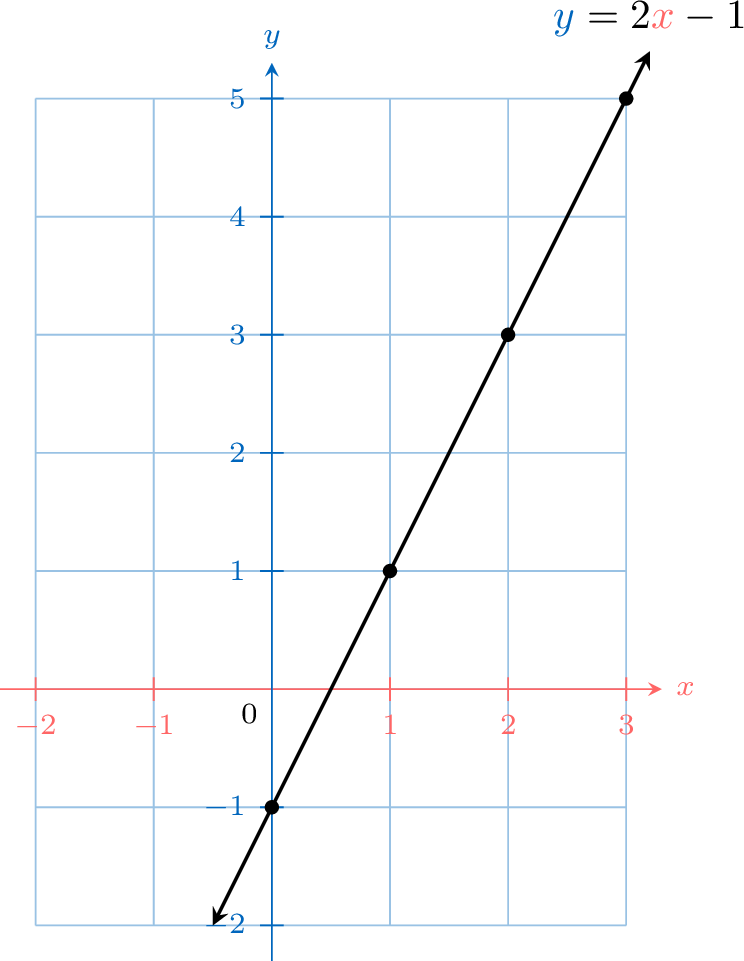

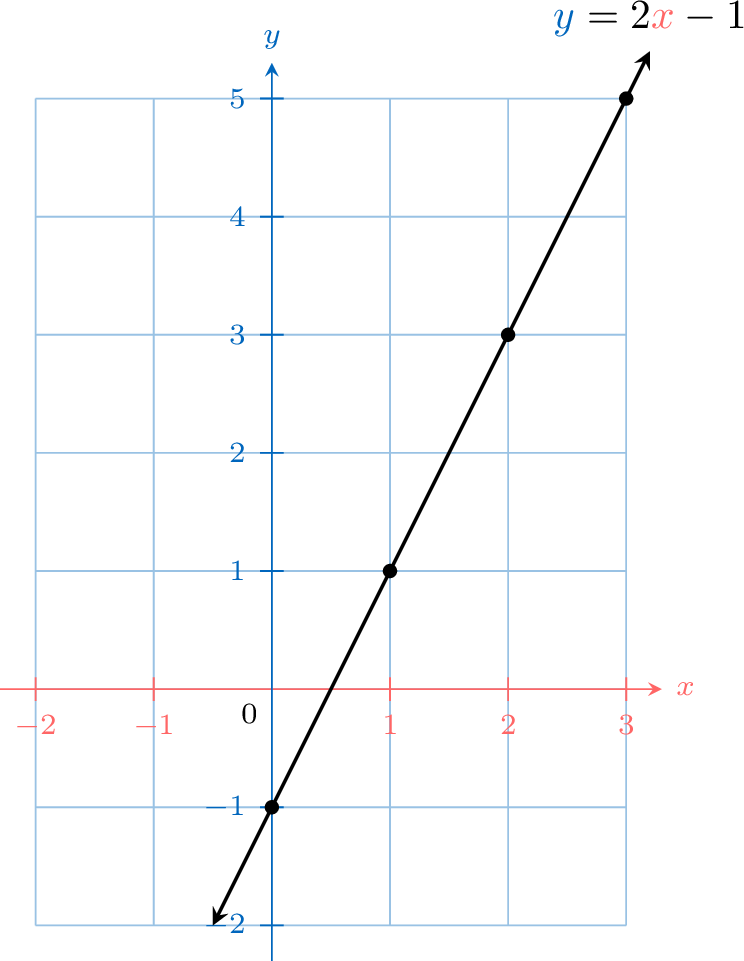

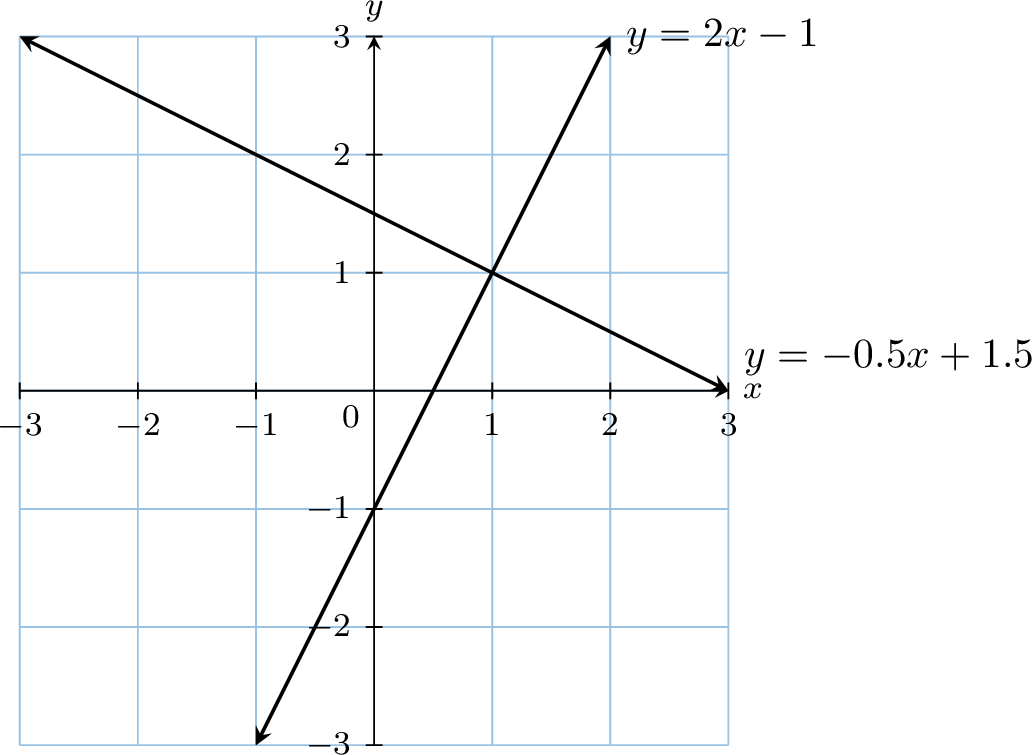

An equation like \(\textcolor{colorprop}{y}=2\textcolor{colordef}{x}-1\) describes a relationship between the variables \(\textcolor{colordef}{x}\) and \(\textcolor{colorprop}{y}\). For any value of \(\textcolor{colordef}{x}\) we choose, the equation tells us the corresponding value of \(\textcolor{colorprop}{y}\).

We can use this to find coordinates \((\textcolor{colordef}{x}, \textcolor{colorprop}{y})\) for points that satisfy the equation.

We can use this to find coordinates \((\textcolor{colordef}{x}, \textcolor{colorprop}{y})\) for points that satisfy the equation.

- If \(\textcolor{colordef}{x} = \textcolor{colordef}{1}\), then \(\textcolor{colorprop}{y} = 2(\textcolor{colordef}{1}) - 1 = \textcolor{colorprop}{1}\). This gives us the point \((1, 1)\).

- If \(\textcolor{colordef}{x} = \textcolor{colordef}{2}\), then \(\textcolor{colorprop}{y} = 2(\textcolor{colordef}{2}) - 1 = \textcolor{colorprop}{3}\). This gives us the point \((2, 3)\).

| \(\textcolor{colordef}{x}\) | \(\textcolor{colordef}{0}\) | \(\textcolor{colordef}{1}\) | \(\textcolor{colordef}{2}\) | \(\textcolor{colordef}{3}\) |

| \(\textcolor{colorprop}{y}\) | \(\textcolor{colorprop}{-1}\) | \(\textcolor{colorprop}{1}\) | \(\textcolor{colorprop}{3}\) | \(\textcolor{colorprop}{5}\) |

Definition Slope-Intercept Form

The slope-intercept form of a line's equation is:$$y = mx + c$$where \(m\) is the slope (gradient) and \(c\) is the \(y\)-intercept.

For a vertical line, the equation is \( x = k \) where \(k\) is a constant.

For a vertical line, the equation is \( x = k \) where \(k\) is a constant.

Example

Definition General Form of Equation of a Line

The general form of the equation of a line is:$$ax + by = d$$where \(a\), \(b\), and \(d\) are constants, and \(a\) and \(b\) are not both zero.

Graphing Line Equations

Method Graphing a Line Using Two Points

To graph a line given by \(y = mx + c\):

- Find the first point \((x_1, y_1)\):

- Choose any convenient value for \(x_1\) (often an integer).

- Substitute \(x_1\) into the equation to calculate \(y_1\).

- Find a second point \((x_2, y_2)\):

- Choose a different value for \(x_2\).

- Substitute \(x_2\) into the equation to calculate \(y_2\).

- Draw the line:

- Plot both points on a graph.

- Use a ruler to draw a straight line passing through both points.

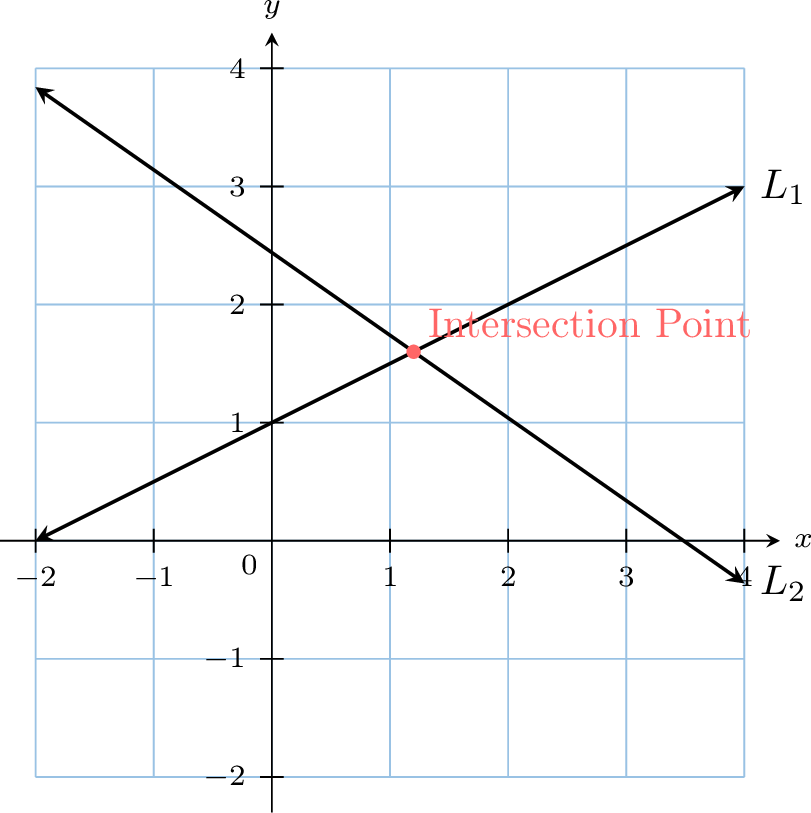

Example

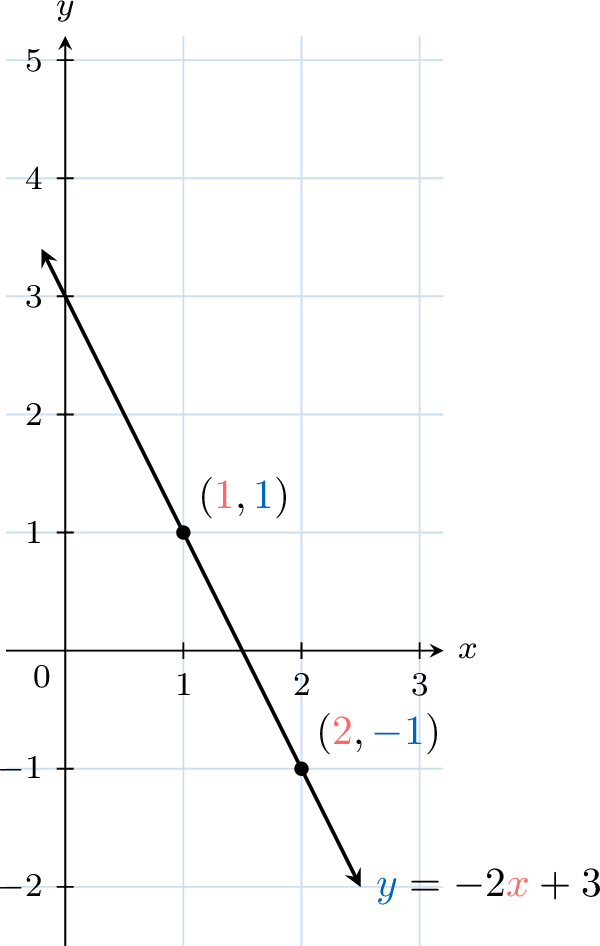

Graph the line \(y = -2x + 3\).

- For \(\textcolor{colordef}{x} = \textcolor{colordef}{1}\),$$\begin{aligned}[t]\textcolor{colorprop}{y} &= -2 \times \textcolor{colordef}{1} + 3 \\ &= \textcolor{colorprop}{1}\end{aligned}$$

- For \(\textcolor{colordef}{x} = \textcolor{colordef}{2}\),$$\begin{aligned}[t]\textcolor{colorprop}{y} &= -2 \times \textcolor{colordef}{2} + 3 \\ &= \textcolor{colorprop}{-1}\end{aligned}$$

- So, the points \((\textcolor{colordef}{1}, \textcolor{colorprop}{1})\) and \((\textcolor{colordef}{2}, \textcolor{colorprop}{-1})\) are on the graph.

Method Graphing a Line Using the \(y\)-Intercept and Slope

To graph a line \(y = mx + c\):

- Plot the \(y\)-intercept:

- Mark the point \((0, c)\) on the graph.

- Use the slope \(m\) to find a second point:

- From \((0, c)\), move horizontally by a chosen amount \(\Delta x\) (for example, \(1\) or \(2\) units).

- Then move vertically by \(\Delta y = m \cdot \Delta x\).

- Mark the second point.

- Draw the line:

- Draw a straight line passing through both points.

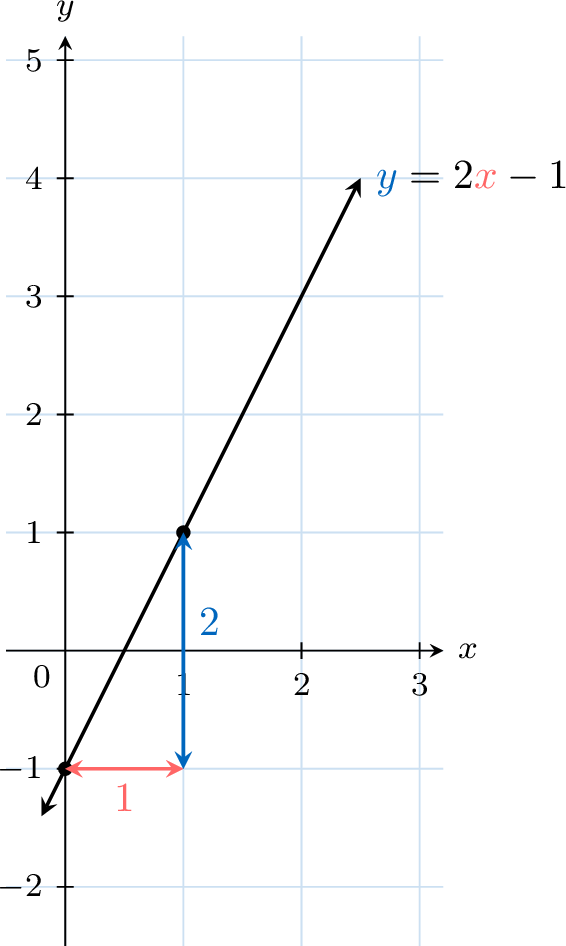

Example

Graph the line \(y = 2x - 1\).

- The \(y\)-intercept is \(-1\), so plot the point \((0, -1)\).

- The slope is \(2\): from \((0, -1)\), move \(1\) unit right (\(\Delta x = 1\)), then \(2\) units up (\(\Delta y = 2\)), to reach \((1, 1)\).

- Draw the line through these two points.

Parallel and Perpendicular Lines

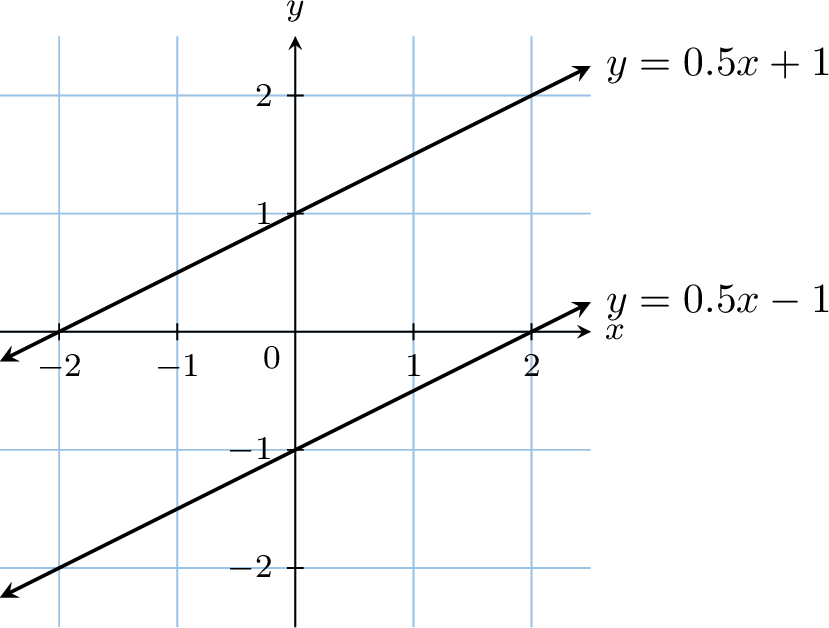

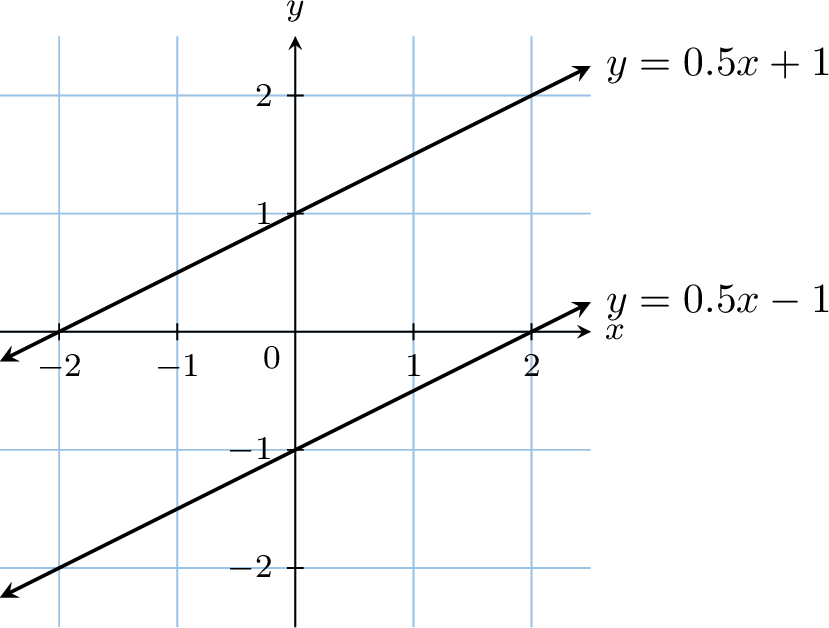

Proposition Parallel Lines

Two distinct, non-vertical lines$$L_1 : y = m_1 x + c_1 \quad \text{and} \quad L_2 : y = m_2 x + c_2$$are parallel if and only if they have the same slope (gradient), i.e.\ \(m_1 = m_2\). If also \(c_1 = c_2\), then the two equations represent the same line.

All vertical lines (of the form \(x = k\)) are parallel to each other.

All vertical lines (of the form \(x = k\)) are parallel to each other.

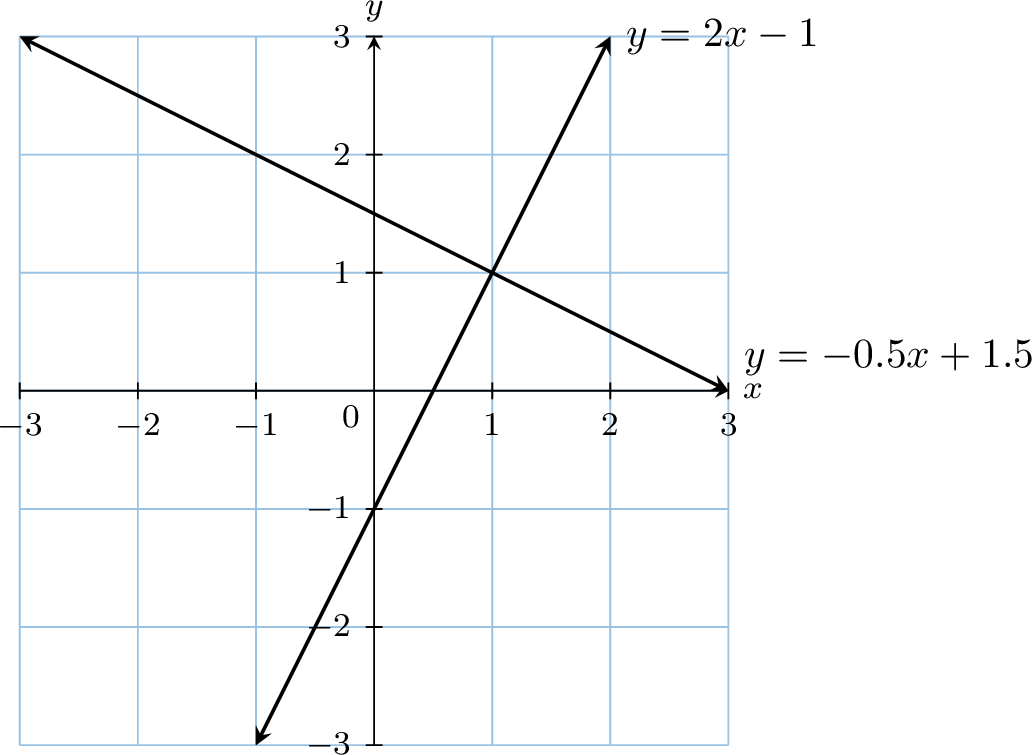

Proposition Perpendicular Lines

Two non-vertical lines are perpendicular if and only if the product of their slopes \(m_1\) and \(m_2\) is \(-1\), i.e.\ \(m_1 \cdot m_2 = -1\). Equivalently, their gradients are negative reciprocals:$$m_2 = -\frac{1}{m_1}.$$Additionally, a vertical line (undefined slope) is always perpendicular to a horizontal line (slope \(0\)).

Example

Determine if the lines \(y=3x+2\) and \(y=3x-1\) are parallel, perpendicular, or neither.

Both lines have slope \(m=3\), so they are parallel (and distinct, since \(2 \neq -1\)).

Example

Determine if the lines \(y=4x-3\) and \(y=-\frac{1}{4}x+5\) are parallel, perpendicular, or neither.

The slopes are \(m_1=4\) and \(m_2=-\dfrac{1}{4}\), and \(4 \times \left(-\dfrac{1}{4}\right) = -1\), so they are perpendicular.

Perpendicular Bisector

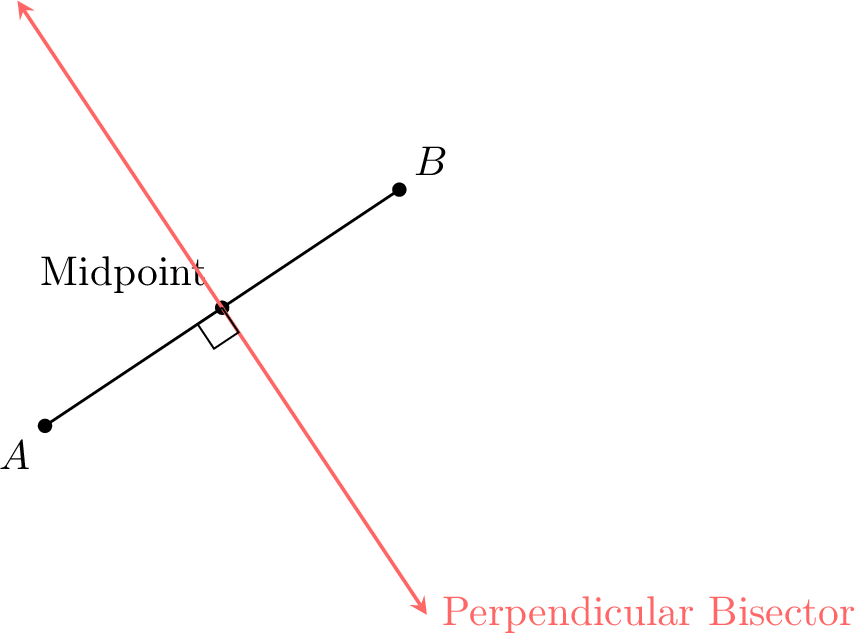

Definition Perpendicular Bisector

The perpendicular bisector of a line segment is a line that is perpendicular to the segment and passes through its midpoint.

Method Finding the Equation of a Perpendicular Bisector

To find the equation of the perpendicular bisector of the segment joining \(A(x_A, y_A)\) and \(B(x_B, y_B)\) (with \(A \neq B\)):

- Find the slope of the segment \(\overline{AB}\) (when \(x_A \neq x_B\)): $$ m_{AB} = \frac{y_B - y_A}{x_B - x_A}. $$

- Find the slope of the perpendicular line (\(m_\perp\)) when \(m_{AB} \neq 0\): $$ m_\perp = -\frac{1}{m_{AB}}. $$

- Find the midpoint of \(\overline{AB}\): $$ M = \left(\frac{x_A+x_B}{2}, \frac{y_A+y_B}{2}\right). $$

- Use the point-slope form with the midpoint \(M(x_M,y_M)\) and perpendicular slope \(m_\perp\): $$ y - y_M = m_\perp(x - x_M). $$

- If \(AB\) is horizontal (\(m_{AB}=0\)), then the perpendicular bisector is a vertical line \(x = x_M\).

- If \(AB\) is vertical (\(x_A = x_B\)), then the perpendicular bisector is a horizontal line \(y = y_M\).

Example

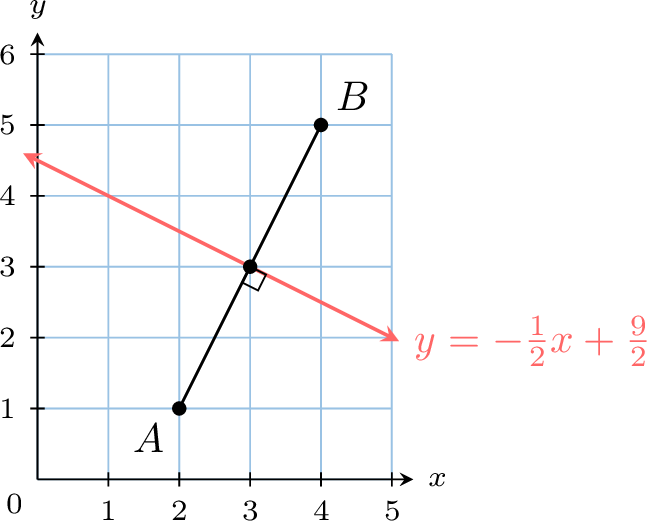

Find the equation of the perpendicular bisector of the line segment with endpoints \(A(2, 1)\) and \(B(4, 5)\).

- The slope of the segment \(\Segment{AB}\) is$$m_{\Segment{AB}} = \frac{5-1}{4-2} = \frac{4}{2} = 2.$$

- The slope of the perpendicular bisector is \(m_\perp = -\dfrac{1}{2}\).

- The midpoint of \(\Segment{AB}\) is$$M = \left(\frac{2+4}{2}, \frac{1+5}{2}\right) = (3, 3).$$

- Using the point-slope form \(y-y_1 = m(x-x_1)\) with point \((3,3)\) and slope \(-\dfrac{1}{2}\): $$ \begin{aligned} y-3 &= -\frac{1}{2}(x-3) \\ y-3 &= -\frac{1}{2}x + \frac{3}{2} \\ y &= -\frac{1}{2}x + \frac{3}{2} + 3 \\ y &= -\frac{1}{2}x + \frac{9}{2}. \end{aligned} $$

Intersection of Two Lines

Definition Intersection of Lines

The intersection of two non-parallel lines is the single point where they cross or meet. The coordinates of this point must satisfy the equations of both lines. If two lines are parallel and distinct, they have no point of intersection; if they have the same equation, they intersect at infinitely many points (they are the same line).

Method Finding the Intersection of Two Lines

To find the point of intersection of two lines given by \(y = m_1x + c_1\) and \(y = m_2x + c_2\):

- Check the gradients.

- If \(m_1 = m_2\) and \(c_1 \neq c_2\), the lines are parallel and there is no point of intersection.

- If \(m_1 = m_2\) and \(c_1 = c_2\), the lines coincide and have infinitely many common points.

- If \(m_1 \neq m_2\), continue to the next steps.

- Set the expressions for \(y\) equal to each other, since at the intersection point, the \(y\)-coordinates are the same: $$ m_1x + c_1 = m_2x + c_2. $$

- Solve for \(x\). This will give the \(x\)-coordinate of the intersection.

- Substitute the value of \(x\) back into either of the original line equations to find the corresponding \(y\)-coordinate.

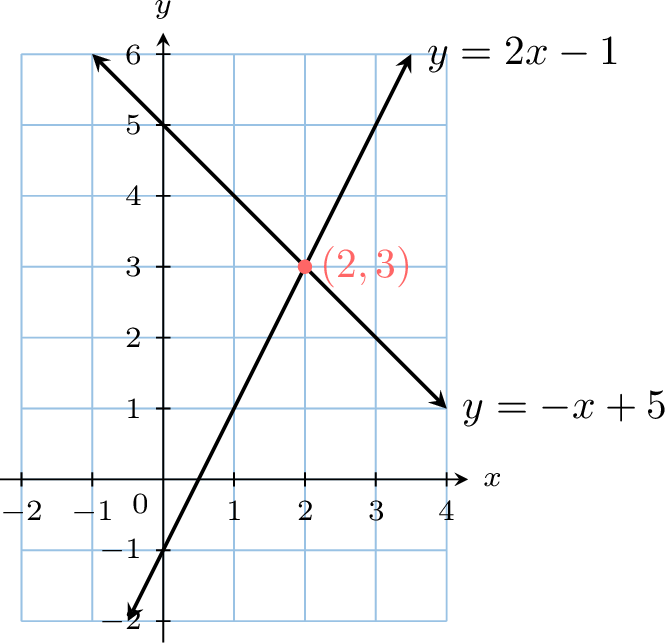

Example

Find the point of intersection of the lines \(y=2x-1\) and \(y=-x+5\).

- Set the expressions for \(y\) equal to each other: $$ 2x-1 = -x+5. $$

- Solve for \(x\): $$ \begin{aligned} 2x + x &= 5 + 1 \\ 3x &= 6 \\ x &= 2. \end{aligned} $$

- Substitute \(x=2\) into either equation to find \(y\): $$ y = 2(2) - 1 = 4-1 = 3. $$

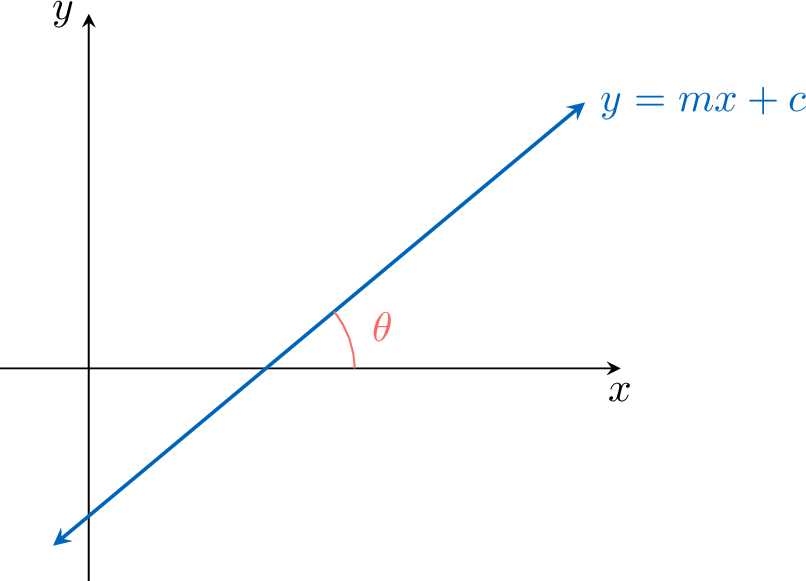

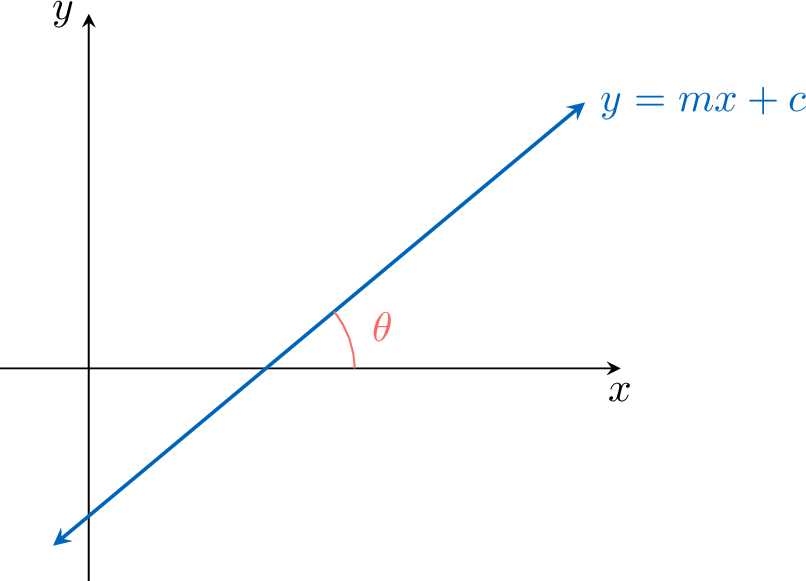

Gradient and the Angle of Inclination

Proposition Gradient in Terms of Angle

If a (non-vertical) straight line makes an angle of \(\theta\) with the positive \(x\)-axis (measured anticlockwise), then its gradient is given by the formula$$m = \tan \theta.$$For a line in the first or second quadrant, the (principal) angle of inclination is usually taken with \(0^\circ < \theta < 180^\circ\) and \(\theta \neq 90^\circ\).