Maclaurin Series

Many complex functions, especially transcendental functions like \(\sin(x)\) and \(e^x\), can be difficult to evaluate without a calculator. However, we can approximate these functions using something simpler: polynomials. This is the central idea behind Maclaurin series.

By matching a function's value and all its derivatives at a single point, \(x=0\), with those of a power series, we obtain the Maclaurin series of the function. The partial sums of this series are polynomials that approximate the function near \(x=0\), and on an interval of convergence the infinite series can even give exact equality. This chapter introduces the method for constructing these polynomial approximations, presents the standard series you must know, and explores their applications.

By matching a function's value and all its derivatives at a single point, \(x=0\), with those of a power series, we obtain the Maclaurin series of the function. The partial sums of this series are polynomials that approximate the function near \(x=0\), and on an interval of convergence the infinite series can even give exact equality. This chapter introduces the method for constructing these polynomial approximations, presents the standard series you must know, and explores their applications.

Maclaurin Series

From Approximation to Equality: Building a Polynomial

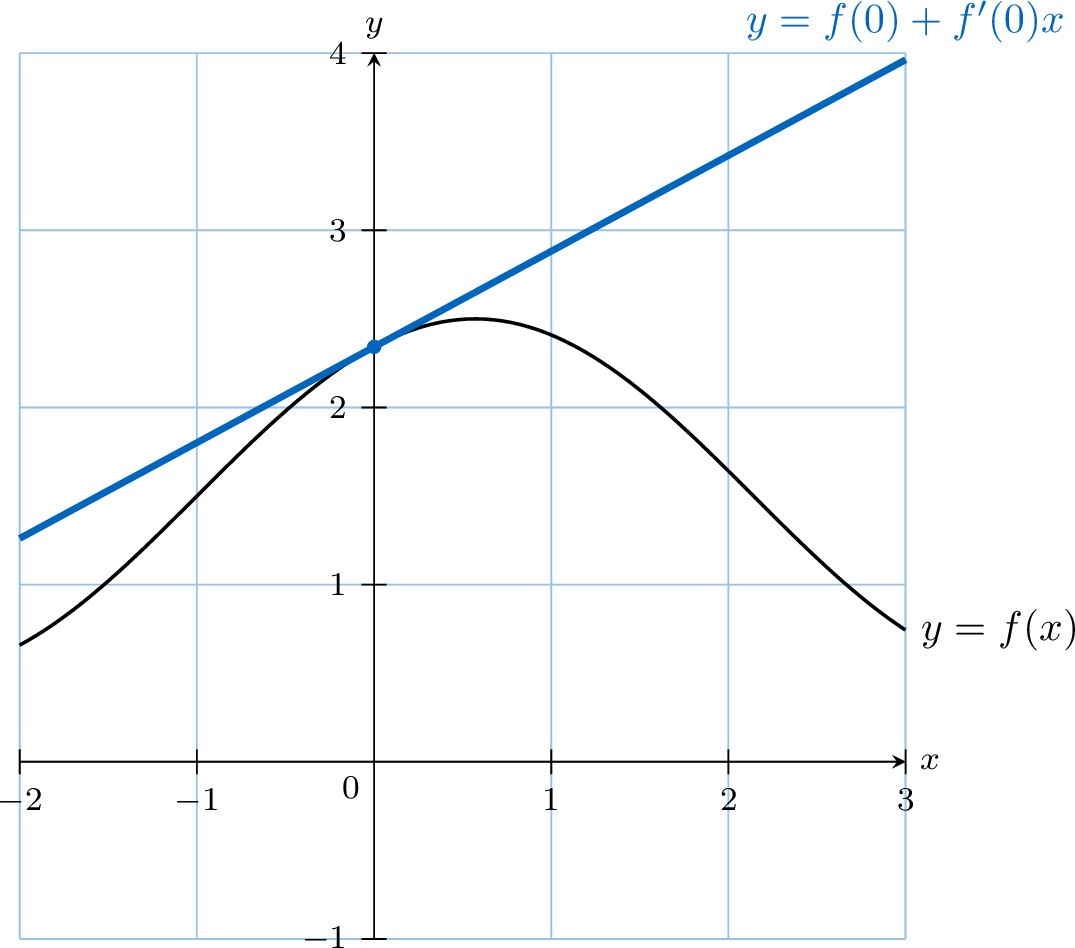

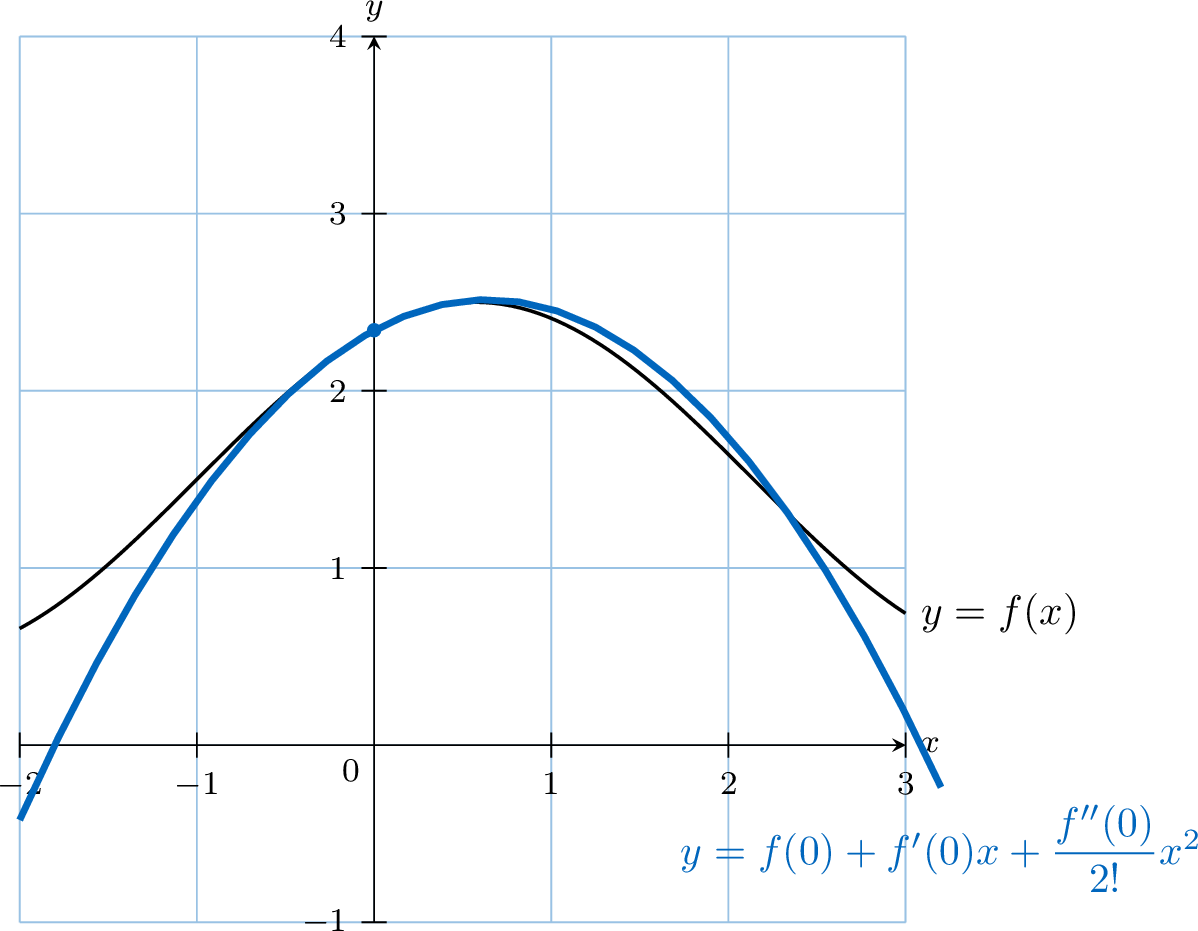

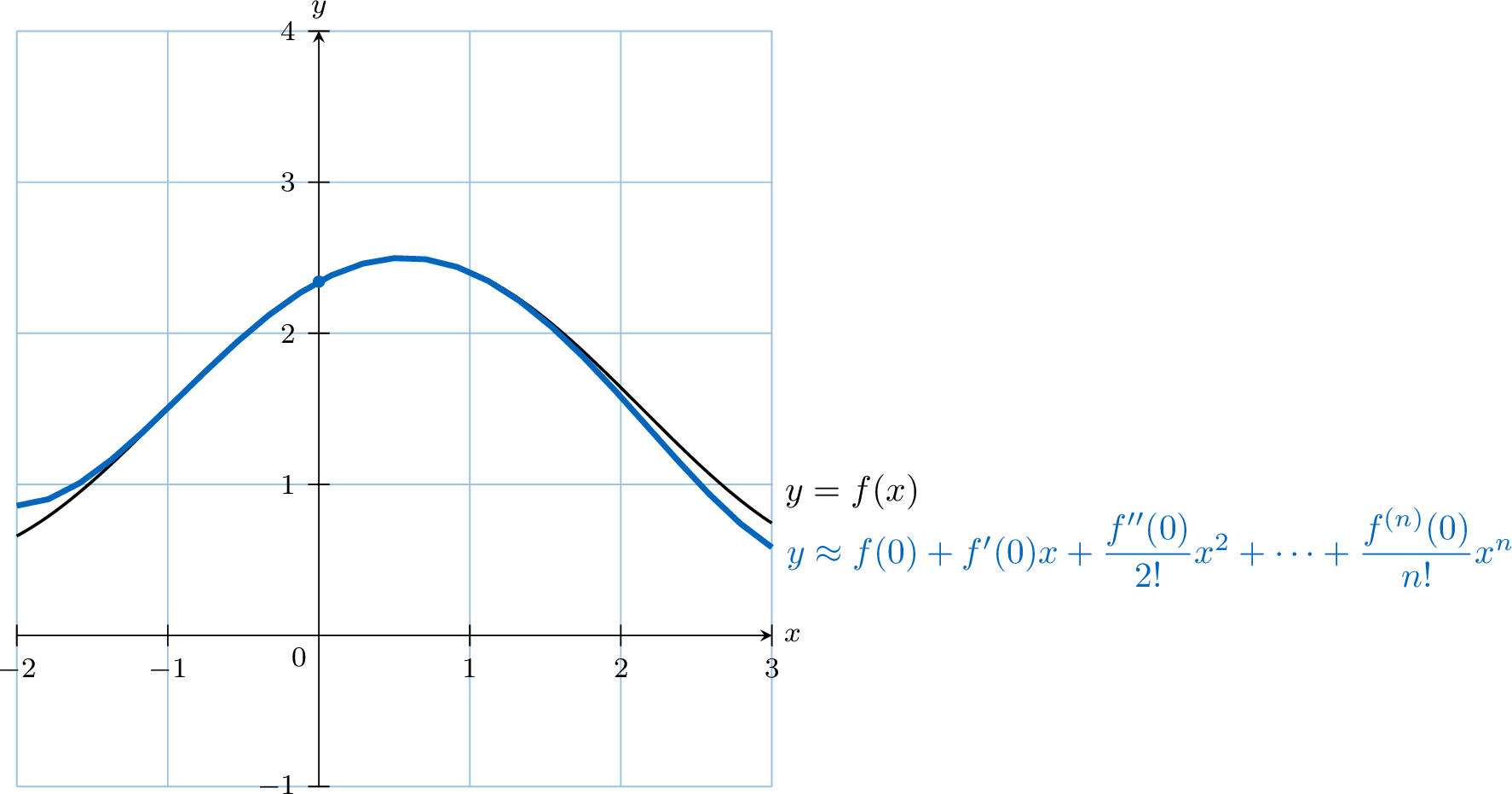

The idea of a Maclaurin series is built upon the familiar concept of linear approximation, which we can improve by adding more terms so that higher-order derivatives match at \(x=0\).

- Linear Approximation (Degree 1): Near \(x=0\), the best linear approximation to \(f(x)\) is the tangent line at that point:$$ f(x) \approx f(0) + f'(0)x. $$This is the first Maclaurin approximation.

- Quadratic Approximation (Degree 2): To get a better approximation near \(x=0\), we add a quadratic term and choose its coefficient so that the second derivative of the approximation also matches that of the function at \(x=0\):$$ f(x) \approx f(0) + f'(0)x + \dfrac{f''(0)}{2!}x^2. $$

- Polynomial Approximation (Degree \(n\)): Continuing this process, a Maclaurin polynomial of degree \(n\) matches the first \(n\) derivatives of the function at \(x=0\):$$f(x) \approx f(0) + f'(0)x + \dfrac{f''(0)}{2!}x^2 + \dots + \dfrac{f^{(n)}(0)}{n!}x^n.$$As \(n\) increases, the polynomial “hugs’’ the function more closely near \(x=0\).

- The Limit: The Maclaurin Series. When we let the degree of the polynomial go to infinity and the resulting infinite series converges to \(f(x)\) (for \(x\) in some interval around \(0\)), the approximation becomes an exact equality there. This infinite series is the Maclaurin series:$$ f(x) = f(0)+f'(0)x+\dfrac{f''(0)}{2!}x^2+\dfrac{f^{(3)}(0)}{3!}x^3+\dots $$or, in compact form,$$ f(x) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \dfrac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!}x^k. $$

Definition Maclaurin Series

The Maclaurin series of a function \(f(x)\) that is infinitely differentiable at \(x=0\) is the power series$$\begin{aligned}f(x) &= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \dfrac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!}x^k \\

&= f(0) + f'(0)x + \dfrac{f''(0)}{2!}x^2 + \dots\end{aligned}$$Whenever this infinite series converges to \(f(x)\) for \(x\) in some interval around \(0\), we say that \(f\) is represented there by its Maclaurin series. The set of values of \(x\) for which the series converges to the function value is called the interval of convergence.

Method Finding a Maclaurin Series

To find the Maclaurin series for a function \(f(x)\):

- Differentiate repeatedly: Find the first few derivatives of the function: \(f'(x), f''(x), f'''(x), \dots\) until a clear pattern emerges.

- Evaluate at \(x=0\): Calculate the value of the function and each derivative at \(x=0\): \(f(0), f'(0), f''(0), \dots\)

- Construct the series: Substitute these values into the Maclaurin series formula$$ f(x) = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \dfrac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!}x^k. $$

Example

Find the Maclaurin series for the function \(f(x)=e^x\).

We follow the three-step method.

- Differentiate: \(f(x)=e^x \implies f^{(k)}(x)=e^x\) for all \(k \ge 0\).

- Evaluate at \(x=0\): \(f^{(k)}(0) = e^0 = 1\) for all \(k\).

- Construct the series: $$ \begin{aligned} e^x &= \dfrac{f(0)}{0!}x^0 + \dfrac{f'(0)}{1!}x^1 + \dfrac{f''(0)}{2!}x^2 + \dots \\ &= \dfrac{1}{0!} + \dfrac{1}{1!}x + \dfrac{1}{2!}x^2 + \dfrac{1}{3!}x^3 + \dots \\ &= 1 + x + \dfrac{x^2}{2} + \dfrac{x^3}{6} + \dots \\ &= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \dfrac{x^k}{k!}. \end{aligned} $$

Proposition Standard Maclaurin Series

- \(e^x\) \(= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \dfrac{x^k}{k!} = 1 + x + \dfrac{x^2}{2!} + \dots\) for \(x \in \mathbb{R}\)

- \(\ln(1+x)\) \(= \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} (-1)^{k-1}\dfrac{x^k}{k} = x - \dfrac{x^2}{2} + \dfrac{x^3}{3} - \dots\) for \(|x| < 1\)

- \(\sin(x)\) \(= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} (-1)^k\dfrac{x^{2k+1}}{(2k+1)!} = x - \dfrac{x^3}{3!} + \dfrac{x^5}{5!} - \dots\) for \(x \in \mathbb{R}\)

- \(\cos(x)\) \(= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} (-1)^k\dfrac{x^{2k}}{(2k)!} = 1 - \dfrac{x^2}{2!} + \dfrac{x^4}{4!} - \dots\) for \(x \in \mathbb{R}\)

- \(\arctan(x)\) \(= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\dfrac{ (-1)^kx^{2k+1}}{2k+1} = x - \dfrac{x^3}{3} + \dfrac{x^5}{5} - \dots\) for \(|x| \le 1\)

- \((1+x)^p\) \(= 1 + px + \dfrac{p(p-1)}{2!}x^2 + \dfrac{p(p-1)(p-2)}{3!}x^3 + \dots\) for \(|x| < 1\) (for any real constant \(p\))

The following series are fundamental and are provided in the formula booklet.

Maclaurin Polynomials for Approximation

Definition Maclaurin Polynomial

A Maclaurin polynomial of degree \(n\), denoted \(P_n(x)\), is the finite sum of the first \(n+1\) terms of the Maclaurin series, used to approximate the function near \(x=0\):$$P_n(x) = \sum_{k=0}^{n} \dfrac{f^{(k)}(0)}{k!}x^k = f(0) + f'(0)x + \dfrac{f''(0)}{2!}x^2 + \dots +\dfrac{f^{(n)}(0)}{n!}x^n.$$

Example

Find the Maclaurin polynomial of degree 4 for the function \(f(x)=e^x\) and use it to approximate \(e^{0.1}\).

From the previous example, the Maclaurin series for \(e^x\) is$$1+x+\dfrac{x^2}{2!}+\dfrac{x^3}{3!}+\dfrac{x^4}{4!}+\dots$$The Maclaurin polynomial of degree \(4\) is:$$P_4(x) = 1+x+\dfrac{x^2}{2}+\dfrac{x^3}{6}+\dfrac{x^4}{24}.$$To approximate \(e^{0.1}\), we calculate \(P_4(0.1)\):$$e^{0.1} \approx 1 + 0.1 + \dfrac{(0.1)^2}{2} + \dfrac{(0.1)^3}{6} + \dfrac{(0.1)^4}{24} \approx 1 + 0.1 + 0.005 + 0.000166\ldots + 0.000004\ldots \approx 1.10517.$$

Substitution and Differentiation/Integration Term-by-Term

A powerful technique is to obtain new series from ones we already know (such as the geometric series), without having to use the derivative formula from scratch every time.

Method Substitution

We can find the series for a composite function \(f(g(x))\) by taking the series for \(f(u)\) and substituting \(u=g(x)\), then adjusting the interval of convergence accordingly.

Example

Starting with the geometric series \(\dfrac{1}{1-u} = \sum_{k=0}^\infty u^k\) for \(|u|<1\), find the Maclaurin series for \(\dfrac{1}{1+x}\).

We use the geometric series formula and substitute \(u = -x\). The condition \(|u|<1\) becomes \(|-x|<1\), which is equivalent to \(|x|<1\).$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{1}{1-u} &= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} u^k \\

\dfrac{1}{1-(-x)} &= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} (-x)^k \quad(\text{letting } u=-x) \\

\dfrac{1}{1+x} &= \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} (-1)^k x^k \\

\dfrac{1}{1+x} &= 1 - x + x^2 - x^3 + \dots \quad\text{for }|x|<1.\end{aligned}$$

Method Differentiation and Integration

We can differentiate or integrate a known Maclaurin series term-by-term within its interval of convergence to find the series for its derivative or integral.

Example

Starting with the series \(\dfrac{1}{1+x} = \sum_{k=0}^\infty (-1)^k x^k\) for \(|x|<1\), find the Maclaurin series for \(\ln(1+x)\).

We know that \(\displaystyle\int_0^u \dfrac{1}{1+x}\, dx = [\ln(1+x)]_0^u = \ln(1+u)\). We integrate the series term-by-term (valid for \(|u|<1\)):$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{1}{1+x} & = 1-x+x^2-x^3+\dots \\

\int_0^u \dfrac{1}{1+x}\, dx & = \int_0^u \left( 1-x+x^2-x^3+\dots\right) \, dx\\

\ln(1+u) & = \int_0^u 1 \, dx-\int_0^u x \, dx+\int_0^u x^2 \, dx-\int_0^u x^3 \, dx+\dots \\

\ln(1+u) & = \left[ x\right]_0^u - \left[\dfrac{x^2}{2}\right]_0^u + \left[\dfrac{x^3}{3}\right]_0^u - \left[\dfrac{x^4}{4}\right]_0^u + \dots \\

\ln(1+u) & = u - \dfrac{u^2}{2} + \dfrac{u^3}{3} - \dfrac{u^4}{4}+\dots\\

\ln(1+x) & = x - \dfrac{x^2}{2} + \dfrac{x^3}{3} - \dfrac{x^4}{4}+\dots\quad(\text{replacing \(u\) with \(x\)})\\

\ln(1+x) & = \sum_{k=1}^\infty (-1)^{k-1}\dfrac{x^k}{k},\quad |x|<1.\end{aligned}$$

Example

Starting with the geometric series \(\dfrac{1}{1-x} = \sum_{k=0}^\infty x^k\) for \(|x|<1\), find the Maclaurin series for \(\dfrac{1}{(1-x)^2}\).

We know that \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\dfrac{1}{1-x}\right) = \dfrac{1}{(1-x)^2}\). We differentiate the series term-by-term (valid for \(|x|<1\)):$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{1}{1-x} & = 1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4+\dots \\

\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\dfrac{1}{1-x}\right) & = \dfrac{d}{dx}\left( 1+x+x^2+x^3+x^4+\dots\right) \\

\dfrac{1}{(1-x)^2} & = \dfrac{d}{dx}\left( 1\right)+\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(x\right)+\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(x^2\right)+\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(x^3\right)+\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(x^4\right)+\dots \\

\dfrac{1}{(1-x)^2} & = 0 + 1 + 2x + 3x^2 + 4x^3 + \dots \\

\dfrac{1}{(1-x)^2} & = \sum_{k=0}^\infty (k+1)x^k,\quad |x|<1.\end{aligned}$$

Linearity of Maclaurin Series

Maclaurin series behave like polynomials: they can be added, subtracted, and multiplied by constants term-by-term. The resulting series will converge on the intersection of the intervals of convergence of the individual series.

Proposition Linearity Property

If the Maclaurin series for \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\) are known, and \(c\) is a constant, then:

- Sum/Difference: The series for \(f(x) \pm g(x)\) is the term-by-term sum/difference of their respective series.

- Scalar Multiple: The series for \(c \cdot f(x)\) is the series for \(f(x)\) with each term multiplied by \(c\).

Example

Find the Maclaurin series for \(f(x) = \cosh(x)\) up to the term in \(x^4\), using the series for \(e^x\) and \(e^{-x}\). (Recall that \(\cosh(x) = \dfrac{e^x + e^{-x}}{2}\).)

First, we write out the series for \(e^x\) and find the series for \(e^{-x}\) by substitution:$$ e^x = 1 + x + \dfrac{x^2}{2!} + \dfrac{x^3}{3!} + \dfrac{x^4}{4!} + \dots $$$$ e^{-x} = 1 - x + \dfrac{x^2}{2!} - \dfrac{x^3}{3!} + \dfrac{x^4}{4!} - \dots $$Now, we add the two series together. Notice that the odd-powered terms cancel out:$$\begin{aligned}e^x + e^{-x}&= (1+1) + (x-x) + \left(\dfrac{x^2}{2!}+\dfrac{x^2}{2!}\right) + \left(\dfrac{x^3}{3!}-\dfrac{x^3}{3!}\right) + \left(\dfrac{x^4}{4!}+\dfrac{x^4}{4!}\right) + \dots \\

&= 2 + 2\dfrac{x^2}{2!} + 2\dfrac{x^4}{4!} + \dots\end{aligned}$$Finally, we multiply the entire series by the scalar \(\dfrac{1}{2}\):$$\cosh(x) = \dfrac{e^x + e^{-x}}{2} = \dfrac{1}{2}\left(2 + 2\dfrac{x^2}{2!} + 2\dfrac{x^4}{4!} + \dots\right) = 1 + \dfrac{x^2}{2!} + \dfrac{x^4}{4!} + \dots$$So, up to the term in \(x^4\),$$\cosh(x) \approx 1 + \dfrac{x^2}{2} + \dfrac{x^4}{24}.$$