Applications of Integration In Geometry

Calculating Geometric Area

In the previous chapter, we defined the definite integral \(\int_a^b f(x)\,dx\) as the signed area between the graph of \(y=f(x)\) and the \(x\)-axis. This means that areas above the x-axis are positive, while areas below are negative.

However, when a problem asks for the geometric area or simply the area of a region, it refers to the physical, positive space the region occupies. In this case, we must ensure that all parts of the region, whether they are above or below the x-axis, contribute a positive value to the total. This section outlines a method for calculating this total geometric area.

However, when a problem asks for the geometric area or simply the area of a region, it refers to the physical, positive space the region occupies. In this case, we must ensure that all parts of the region, whether they are above or below the x-axis, contribute a positive value to the total. This section outlines a method for calculating this total geometric area.

Method Calculating Geometric Area Bounded by a Curve and the x-axis

To find the total geometric area \(\mathcal{A}\) bounded by a curve \(y=f(x)\) and the x-axis from \(x=a\) to \(x=b\):

- Find the \(x\)-intercepts: Determine where the function crosses the \(x\)-axis by solving \(f(x)=0\). Identify any roots \(c_1, c_2, \dots\) that lie within the interval \([a,b]\).

- Split the integral: Divide the main integral into smaller integrals at each intercept found in the previous step.

- Calculate each definite integral: Compute the integral for each sub-interval. Some of these will correspond to positive values (where \(f(x) \ge 0\)) and some to negative values (where \(f(x) \le 0\)).

- Sum the absolute values: The total geometric area is the sum of the absolute values of these integrals. If the integral of a sub-region is negative, take its positive value before adding it to the total.

Example

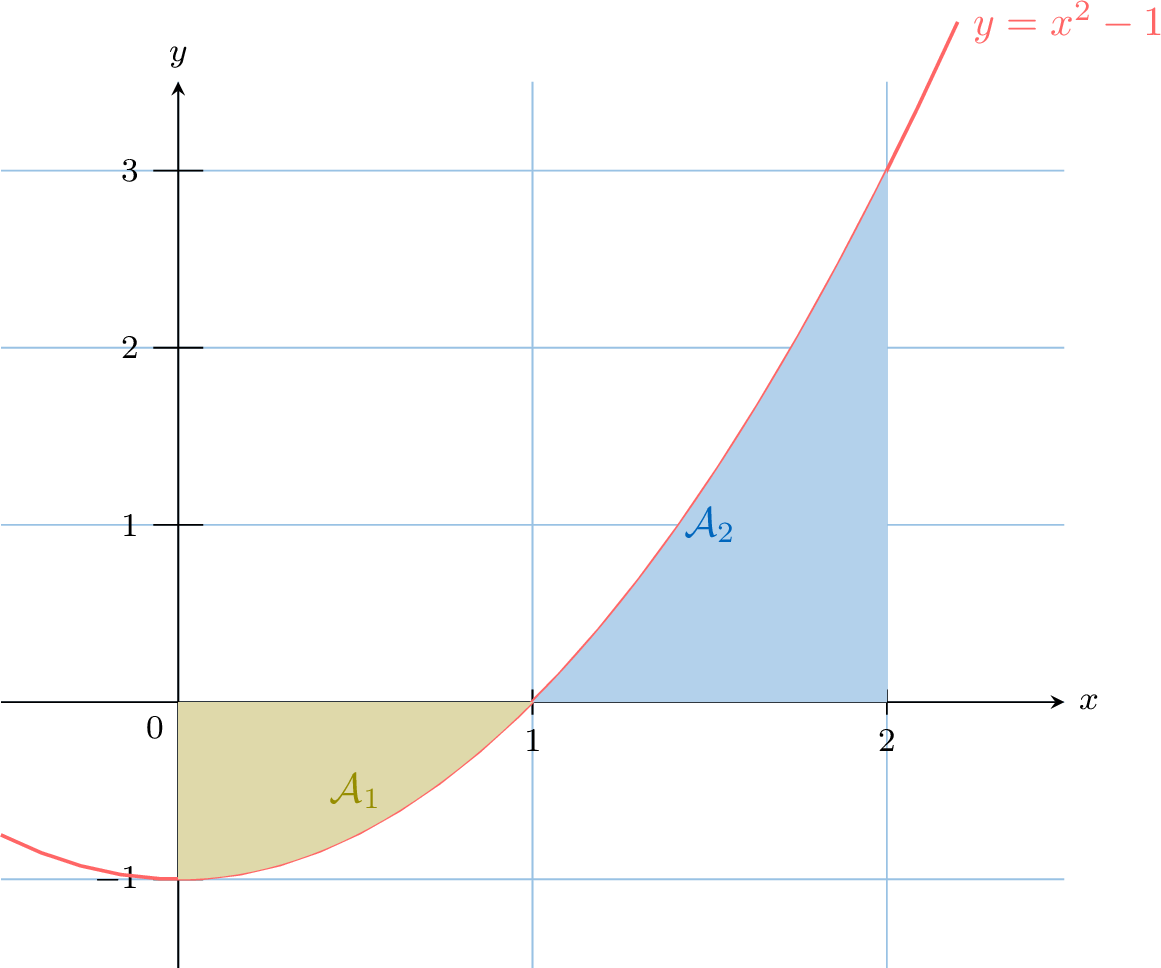

Find the total geometric area between the curve \(y=x^2-1\) and the \(x\)-axis from \(x=0\) to \(x=2\).

- Find intercepts: We solve \(f(x)=x^2-1=0\), which gives roots at \(x=1\) and \(x=-1\). The only root within our interval of integration \([0,2]\) is \(x=1\).

- Split the integral: We must split the total area calculation at \(x=1\).

- From \(x=0\) to \(x=1\), the function is below the \(x\)-axis (Area \(\mathcal{A}_1\)).

- From \(x=1\) to \(x=2\), the function is above the \(x\)-axis (Area \(\mathcal{A}_2\)).

- Calculate each integral: $$ \int_0^1 (x^2-1)\, dx = \left[\frac{x^3}{3}-x\right]_0^1 = \left(\frac{1}{3}-1\right) - 0 = -\frac{2}{3} $$ $$ \int_1^2 (x^2-1)\, dx = \left[\frac{x^3}{3}-x\right]_1^2 = \left(\frac{8}{3}-2\right) - \left(\frac{1}{3}-1\right) = \frac{2}{3} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right) = \frac{4}{3} $$

- Sum the absolute values: $$ \text{Total Area} = \left|-\frac{2}{3}\right| + \left|\frac{4}{3}\right| = \frac{2}{3} + \frac{4}{3} = \frac{6}{3} = 2 $$

Definition Geometric Area Formula

The total geometric area \(\mathcal{A}\) between the graph of a function \(f(x)\) and the \(x\)-axis from \(x=a\) to \(x=b\) is given by the integral of the absolute value of the function:$$ \mathcal{A} = \int_a^b |f(x)|\, \mathrm dx $$

Note

The method of splitting the integral and summing the absolute values is equivalent to this formal definition of the total geometric area.

Area Between Two Curves

We can extend the concept of finding the area under a single curve to find the area of a region enclosed between two different curves. The area under a curve \(y=f(x)\) is a special case where the second curve is simply the \(x\)-axis, \(y=0\).

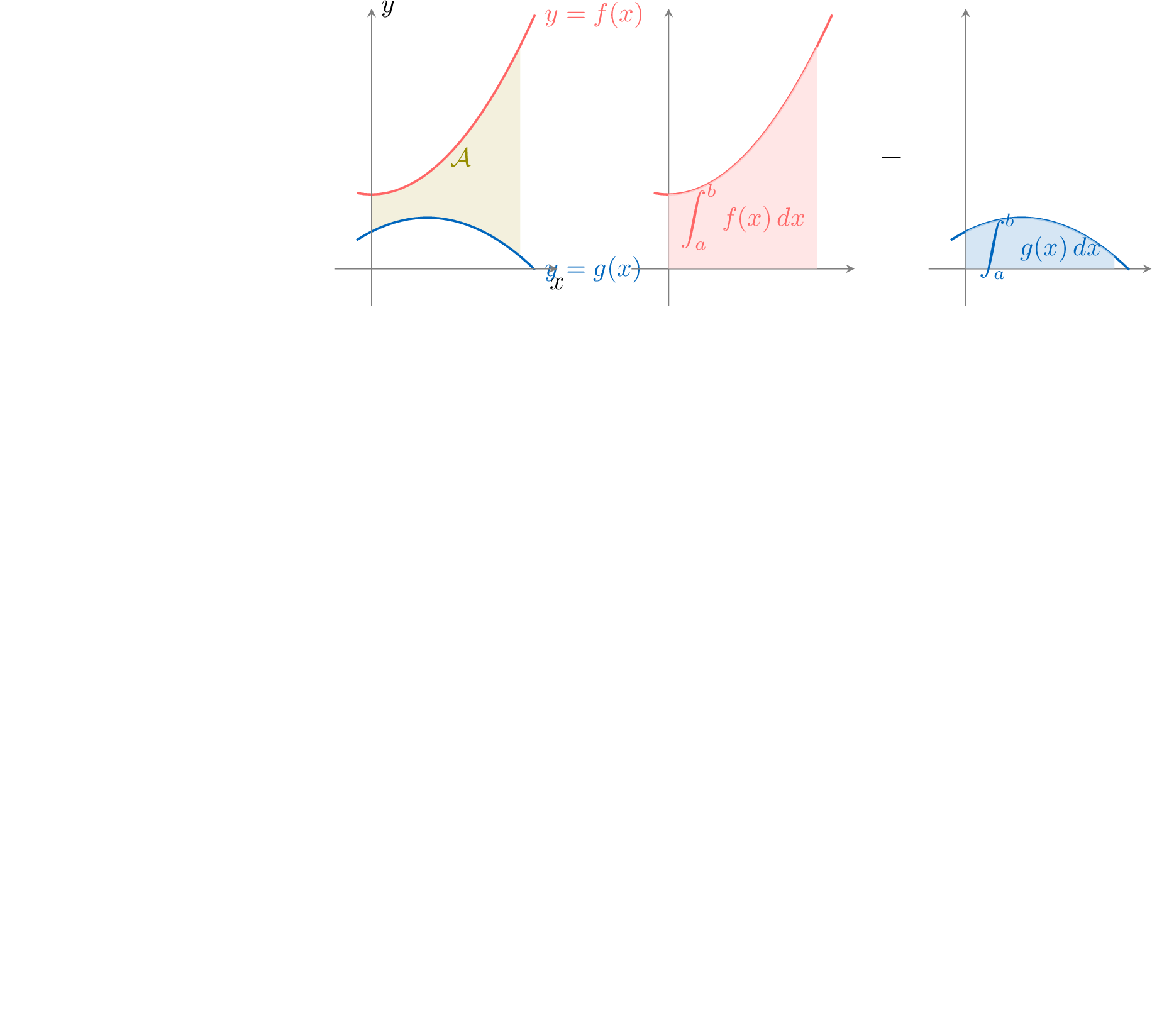

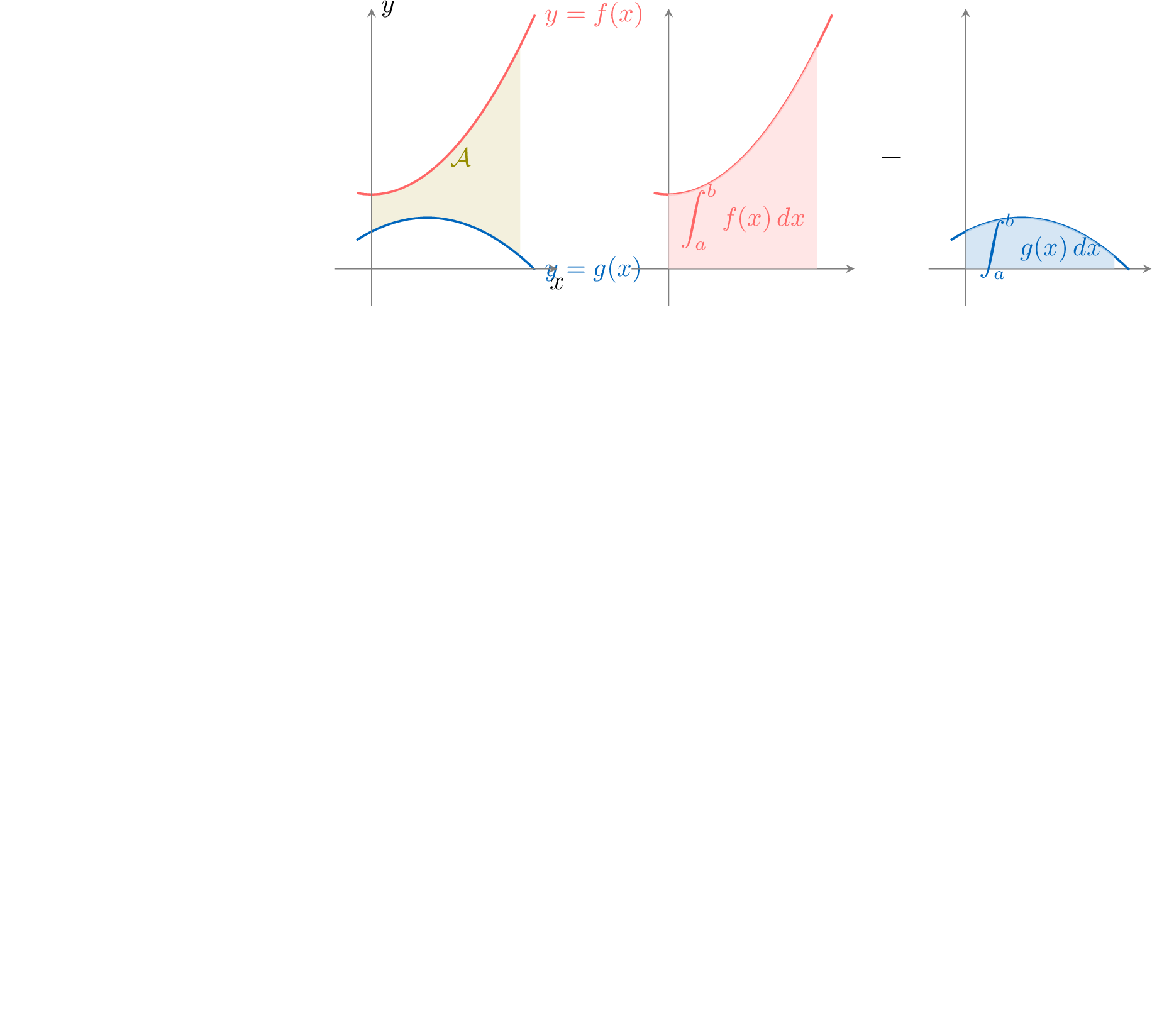

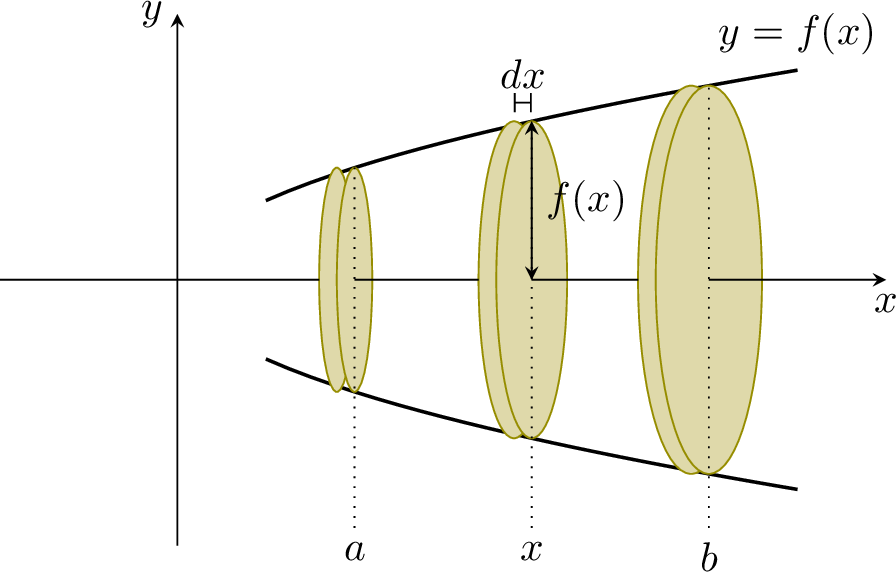

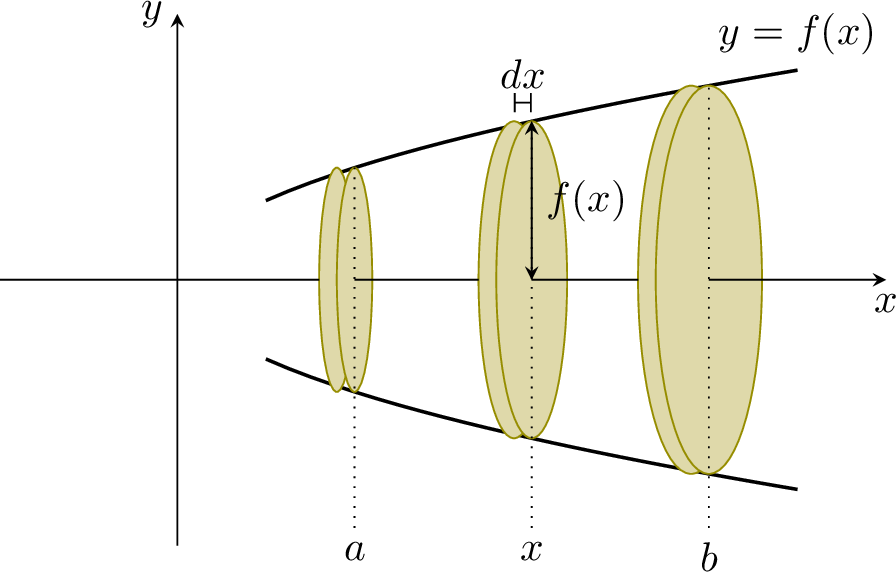

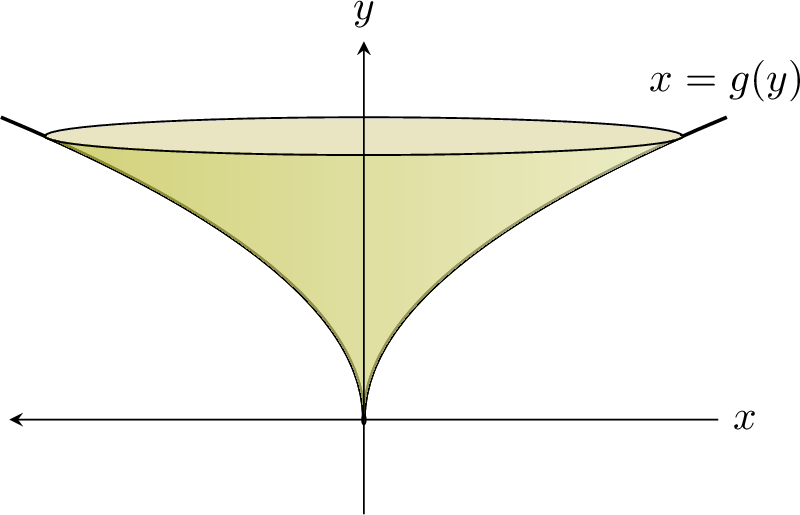

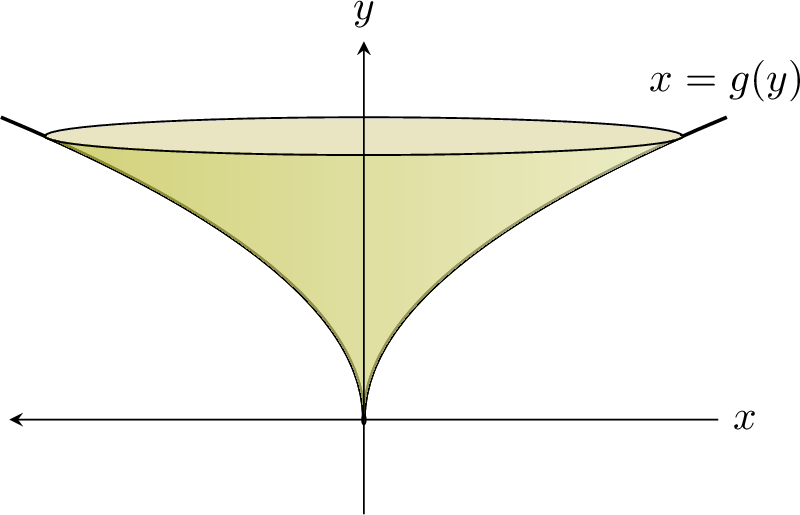

The general idea is intuitive: the area of the region bounded by an upper function \(f(x)\) and a lower function \(g(x)\) is found by calculating the area under \(f(x)\) and subtracting the area under \(g(x)\). Using the linearity of the definite integral, this subtraction can be combined into a single integral:$$\begin{aligned} \textcolor{olive}{\mathcal{A}} &= \textcolor{colordef}{ \int_a^b f(x)\; \mathrm dx} - \textcolor{colorprop}{ \int_a^b g(x)\; \mathrm dx} \\ &= \int_a^b (f(x)-g(x))\; \mathrm dx \end{aligned} $$

The general idea is intuitive: the area of the region bounded by an upper function \(f(x)\) and a lower function \(g(x)\) is found by calculating the area under \(f(x)\) and subtracting the area under \(g(x)\). Using the linearity of the definite integral, this subtraction can be combined into a single integral:$$\begin{aligned} \textcolor{olive}{\mathcal{A}} &= \textcolor{colordef}{ \int_a^b f(x)\; \mathrm dx} - \textcolor{colorprop}{ \int_a^b g(x)\; \mathrm dx} \\ &= \int_a^b (f(x)-g(x))\; \mathrm dx \end{aligned} $$

Proposition Area Between Curves

If \(f(x) \geq g(x)\) for all \(x\) in the interval \([a,b]\), the area \(\mathcal{A}\) of the region enclosed between the curves \(y=f(x)\) and \(y=g(x)\) is given by:$$ \mathcal{A} = \int_a^b (f(x)-g(x))\; \mathrm dx $$

This can be remembered as the integral of the upper function minus the lower function.

Method Calculating the Area Between Two Curves

To find the total geometric area enclosed by two curves \(y=f(x)\) and \(y=g(x)\):

- Find points of intersection. If the limits of integration \(a\) and \(b\) are not given, find them by solving the equation \(f(x)=g(x)\) to determine where the curves cross.

- Identify the upper and lower function. On each interval between intersection points, determine which function is on top. A quick sketch or testing a point is often sufficient.

- Set up and evaluate the integral(s). For each interval, calculate \(\int_a^b (\text{upper function} - \text{lower function}) \, dx\). If the upper and lower functions switch, you will need to set up multiple integrals and (for geometric area) sum their absolute values.

Example

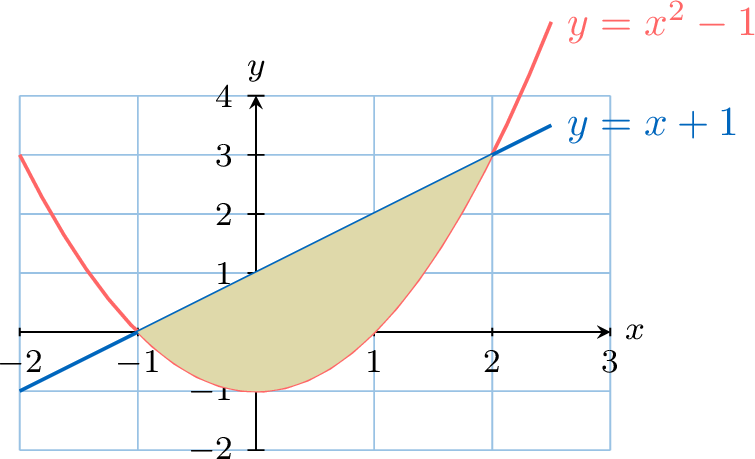

Find the area of the region enclosed by the curves \(y=x+1\) and \(y=x^2-1\).

- Find intersection points: We set the two functions equal to each other: $$ x+1 = x^2-1 \implies x^2-x-2=0 $$ $$ (x-2)(x+1)=0 $$ The curves intersect at \(x=-1\) and \(x=2\). These are our limits of integration.

- Identify the upper function: In the interval \([-1,2]\), let's test the point \(x=0\). For \(y=x+1\), \(y(0)=1\). For \(y=x^2-1\), \(y(0)=-1\). Since \(1 > -1\), the line \(y=x+1\) is the upper function on \([-1,2]\).

- Set up and evaluate: $$\begin{aligned} \mathcal{A} &= \int_{-1}^2 \left( (x+1) - (x^2-1) \right)\, dx \\ &= \int_{-1}^2 (-x^2+x+2)\, dx \\ &= \left[ -\frac{x^3}{3} + \frac{x^2}{2} + 2x \right]_{-1}^2 \\ &= \left(-\frac{8}{3} + \frac{4}{2} + 4\right) - \left(\frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{2} - 2\right) \\ &= \left(-\frac{16}{6} + \frac{12}{6} + \frac{24}{6}\right) - \left(\frac{2}{6} + \frac{3}{6} - \frac{12}{6}\right) \\ &= \frac{20}{6} - \left(\frac{7}{6}\right) \\ &= \frac{27}{6} \\ &= \frac{9}{2} \end{aligned}$$

Volumes of Revolution

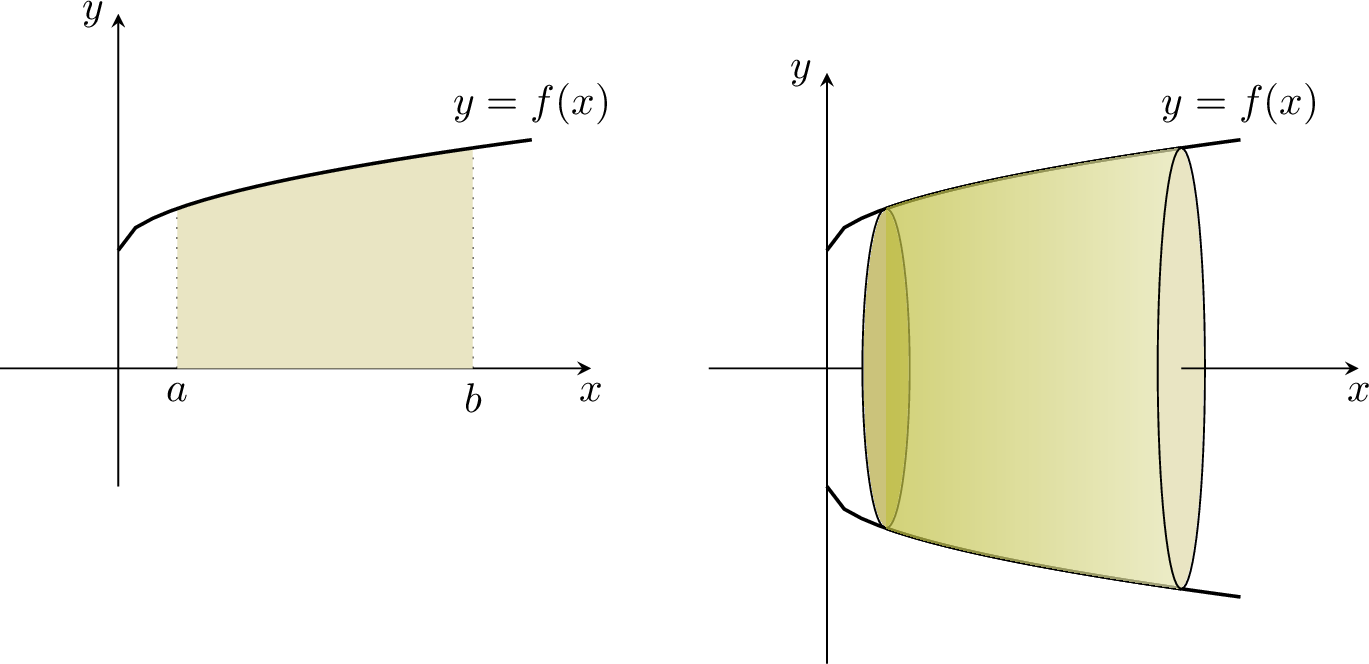

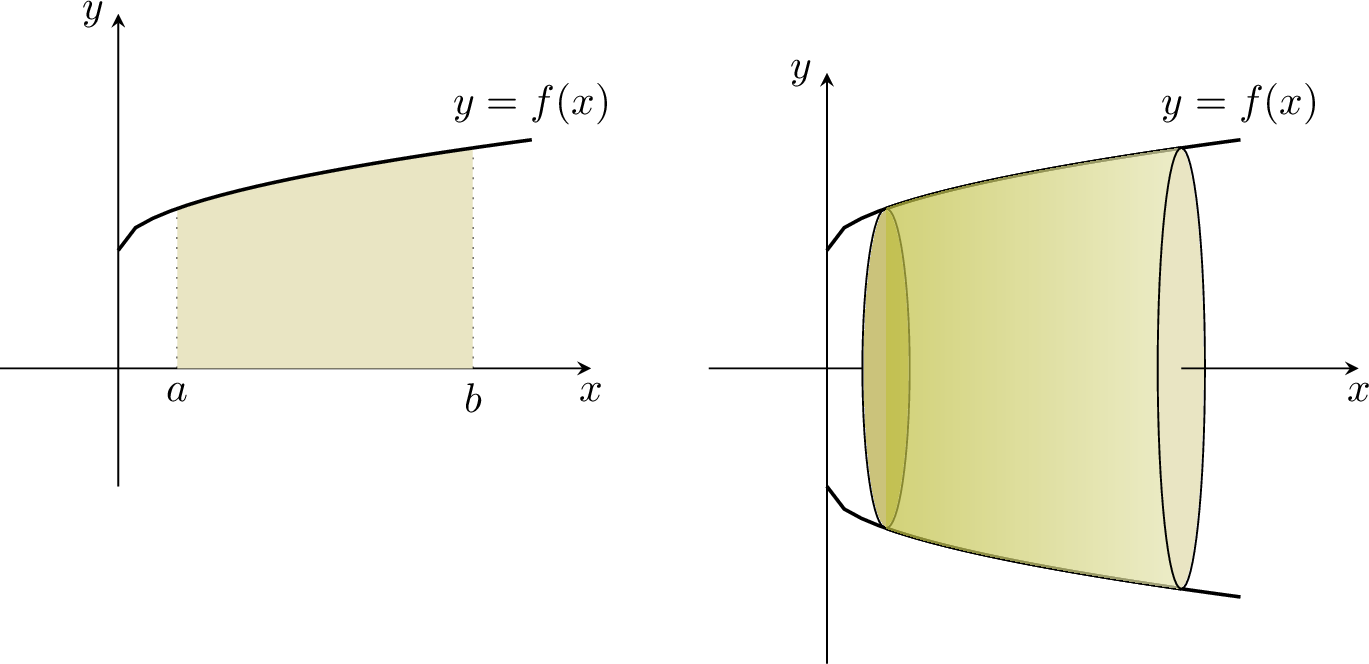

A solid of revolution is a three-dimensional object formed by rotating a two-dimensional shape around an axis. In this section, we will develop a method to find the exact volume of such solids.

Consider the area under the curve \(y=f(x)\) from \(x=a\) to \(x=b\). If we revolve this area \(360^\circ\) (\(2\pi\) radians) around the \(x\)-axis, it sweeps out a solid of revolution.

Consider the area under the curve \(y=f(x)\) from \(x=a\) to \(x=b\). If we revolve this area \(360^\circ\) (\(2\pi\) radians) around the \(x\)-axis, it sweeps out a solid of revolution.

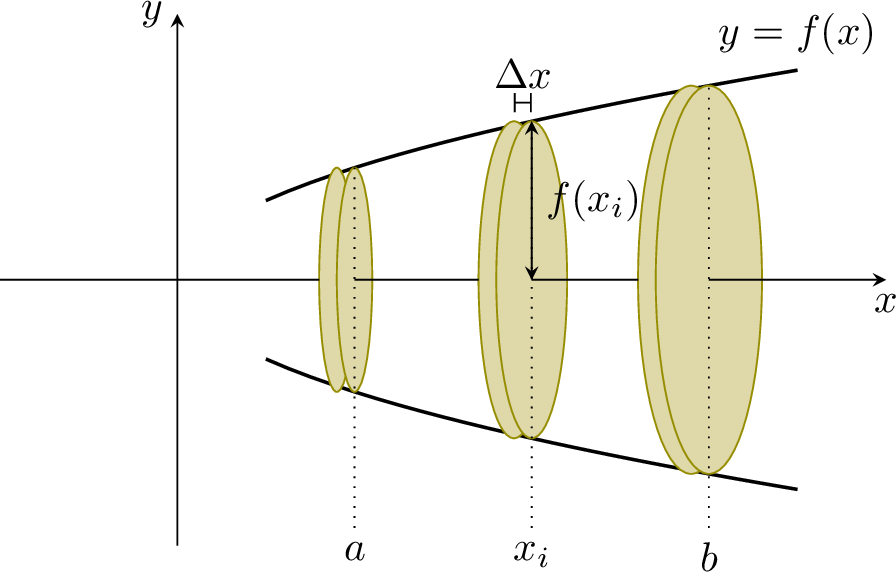

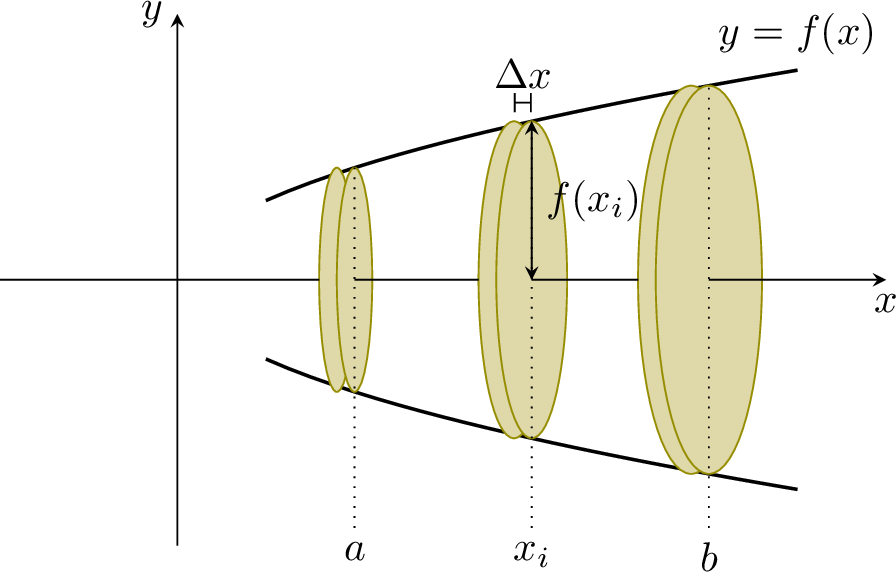

Method The Disk Method

To find the volume of this solid, we use the same strategy as for area: slice the solid into many thin pieces and sum their volumes. In this case, each slice is a thin cylindrical disk. The key insight is that each disk is formed by rotating one of the thin rectangles from a Riemann sum around the \(x\)-axis.

- The radius is the height of the function, \(r = f(x_i)\).

- The height (thickness) of the disk is \(h = \Delta x\).

Proposition Volume of Revolution about the \(x\)-axis

Assuming \(f(x)\geq 0\) on \([a,b]\), the volume \(V\) generated by rotating the region bounded by the curve \(y=f(x)\), the \(x\)-axis, and the lines \(x=a\) and \(x=b\) around the \(x\)-axis is given by:$$ V = \pi \int_a^b [f(x)]^2\, dx $$

Example

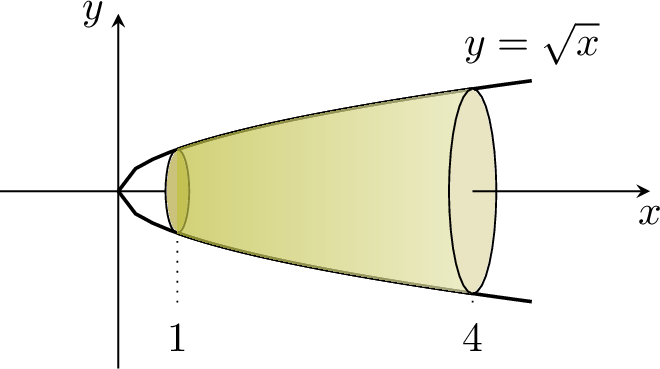

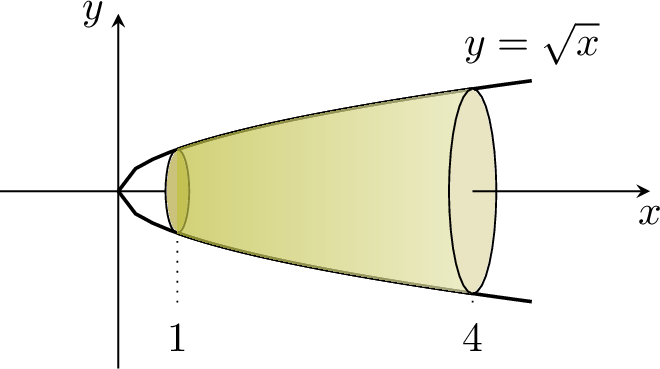

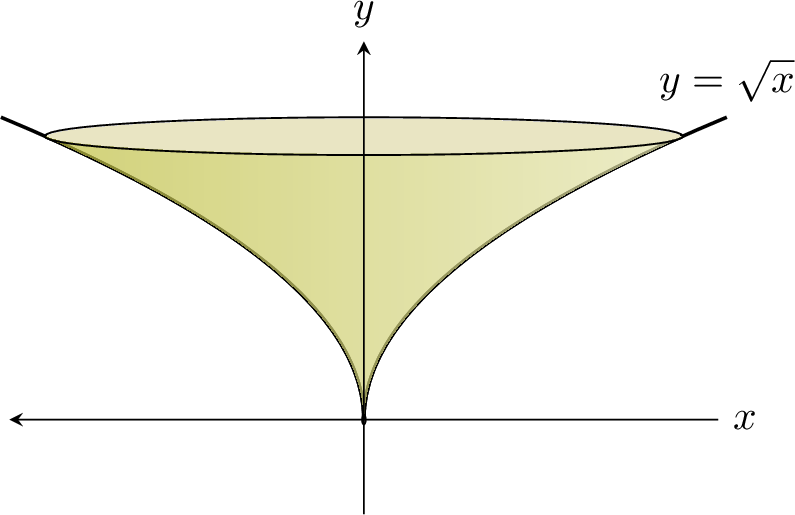

Find the volume of the solid generated by revolving the region under the curve \(y=\sqrt{x}\) from \(x=1\) to \(x=4\) around the \(x\)-axis.

- Identify: The function is \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\), and the limits are \(a=1\) and \(b=4\).

- Square the function: \([f(x)]^2 = (\sqrt{x})^2 = x\).

- Integrate: We set up and evaluate the integral for the volume: $$\begin{aligned} V &= \pi \int_1^4 x \, dx \\ &= \pi \left[ \frac{x^2}{2} \right]_1^4 \\ &= \pi \left( \frac{4^2}{2} - \frac{1^2}{2} \right) \\ &= \pi \left( \frac{16}{2} - \frac{1}{2} \right) \\ &= \pi \left( 8 - \frac{1}{2} \right)\\ &= \frac{15\pi}{2} \end{aligned}$$

Proposition Volume of Revolution about the y-axis

Assuming \(g(y)\ge 0\) on \([c,d]\), the volume \(V\) generated by rotating the region bounded by the curve \(x=g(y)\), the y-axis, and the lines \(y=c\) and \(y=d\) around the y-axis is given by:$$ V = \pi \int_c^d [g(y)]^2\, dy $$

Note

To use this formula, the function must be expressed in the form \(x=g(y)\), where \(y\) is the independent variable. This may require rearranging the function's equation.

Example

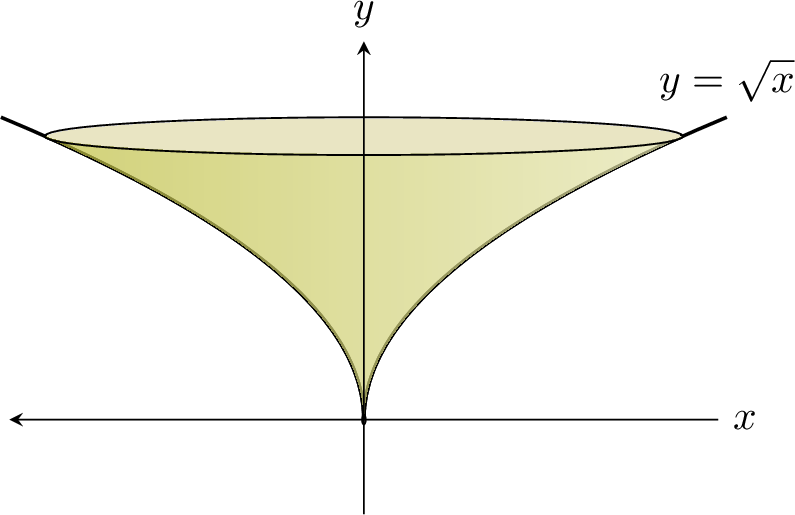

Find the volume of the solid generated by revolving the region bounded by the curve \(y=\sqrt{x}\), the y-axis, and the line \(y=2\) about the y-axis.

- Rearrange the function: The rotation is around the y-axis, so we need to express \(x\) in terms of \(y\): $$ y = \sqrt{x} \implies x = y^2. $$ So, our function is \(g(y)=y^2\).

- Identify limits: The region is bounded by the y-axis (which corresponds to \(x=0\) and starts at \(y=0\), where the curve meets the axis) and the line \(y=2\). So, our limits are \(c=0\) and \(d=2\).

- Integrate: We set up and evaluate the integral for the volume: $$\begin{aligned} V &= \pi \int_0^2 [g(y)]^2\, dy \\ &= \pi \int_0^2 (y^2)^2\, dy \\ &= \pi \int_0^2 y^4\, dy \\ &= \pi \left[ \frac{y^5}{5} \right]_0^2 \\ &= \pi \left( \frac{2^5}{5} - \frac{0^5}{5} \right)\\ &= \frac{32\pi}{5} \end{aligned}$$