Integrals

The measurement of area has been fundamental to science and society since antiquity. In ancient Egypt, surveyors used knotted ropes to construct right angles, allowing them to measure and restore the boundaries of rectangular fields washed away by the annual floods of the Nile. While finding the area of shapes with straight sides is straightforward, calculus provides a revolutionary tool for finding the area of regions bounded by curves.

The Definite Integral as an Area

Approximating Area with Riemann Sums

Method Approximating Area with Riemann Sums

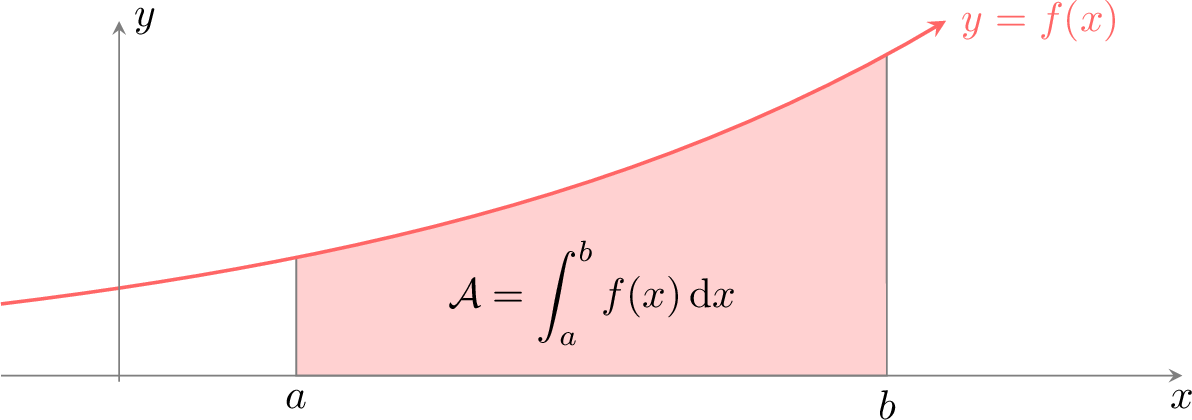

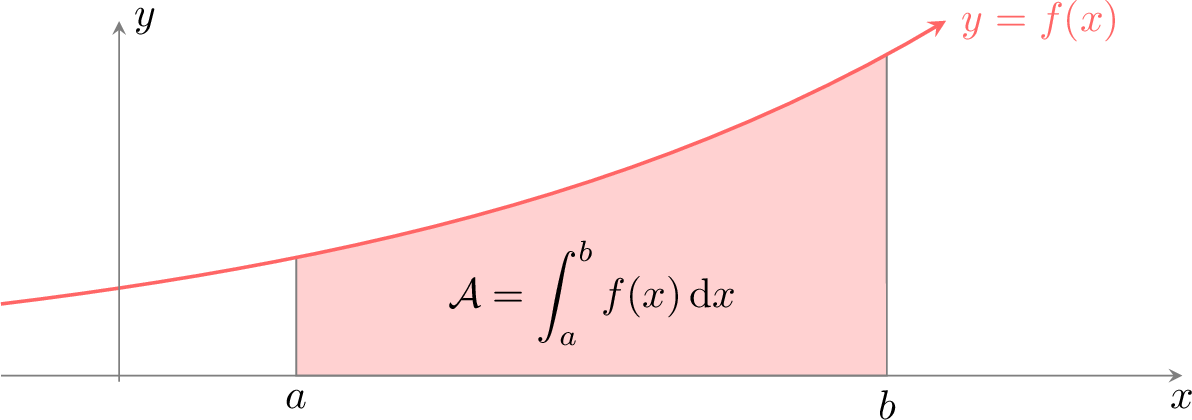

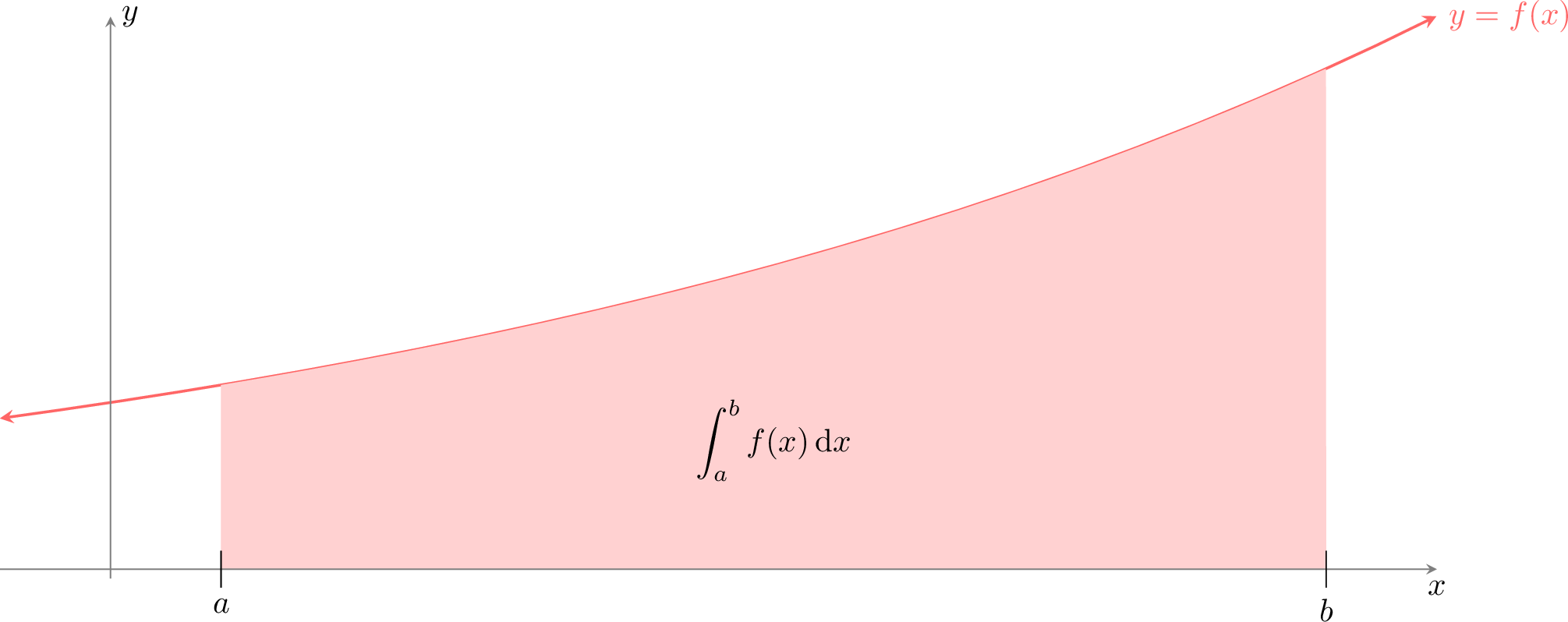

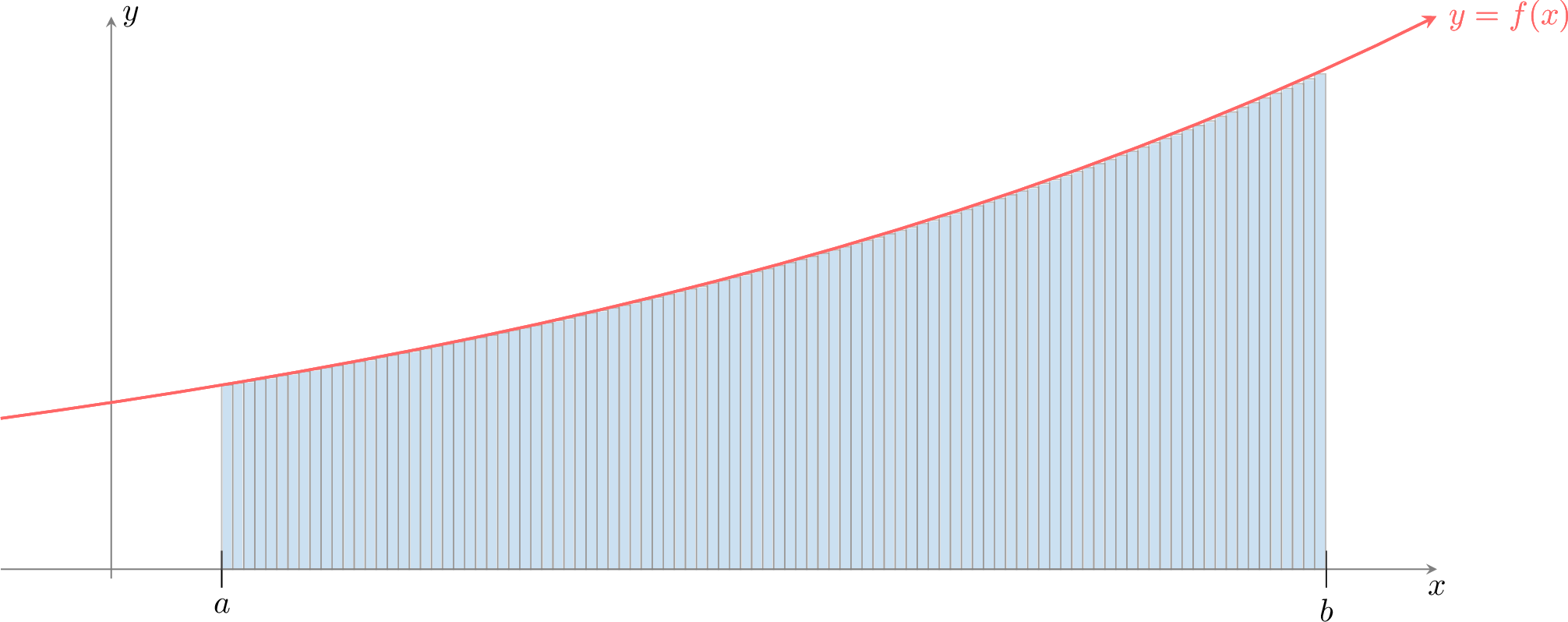

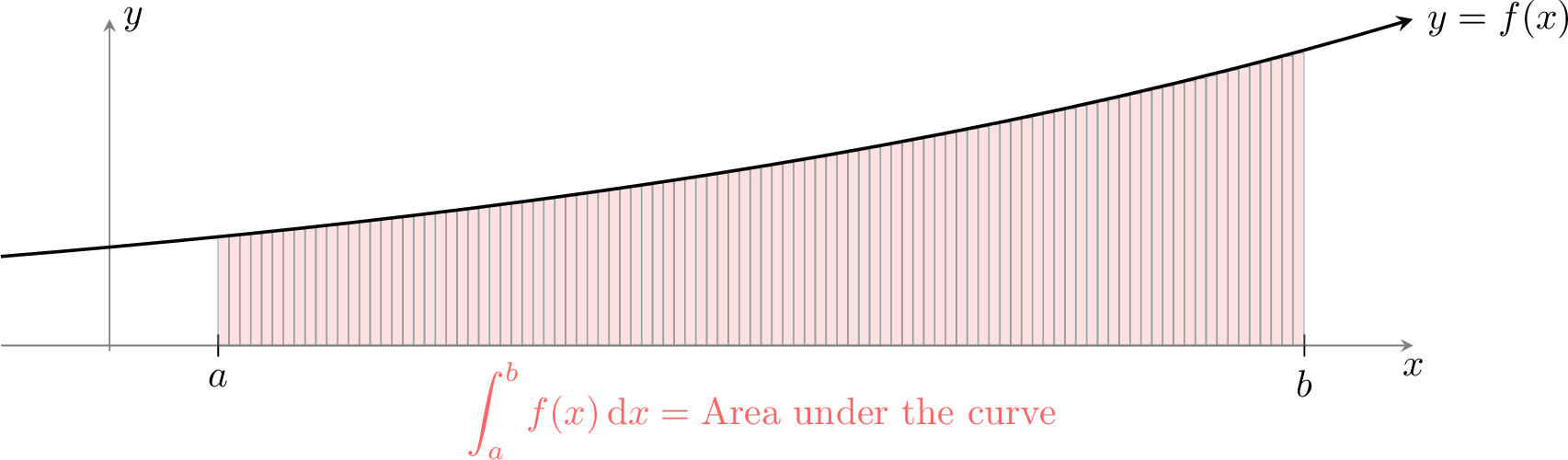

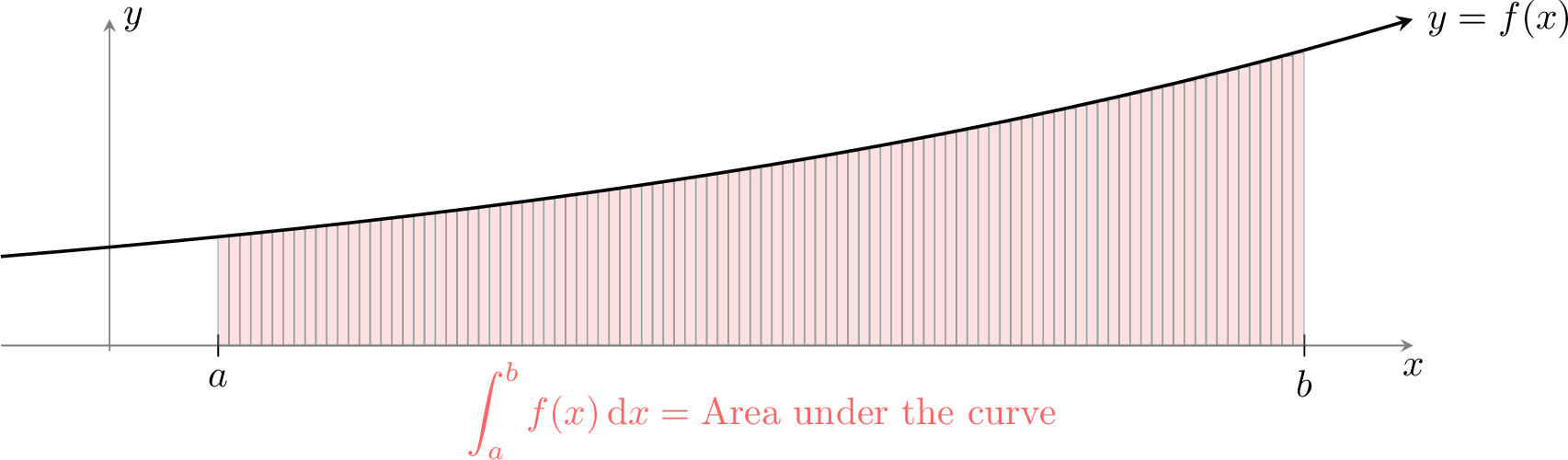

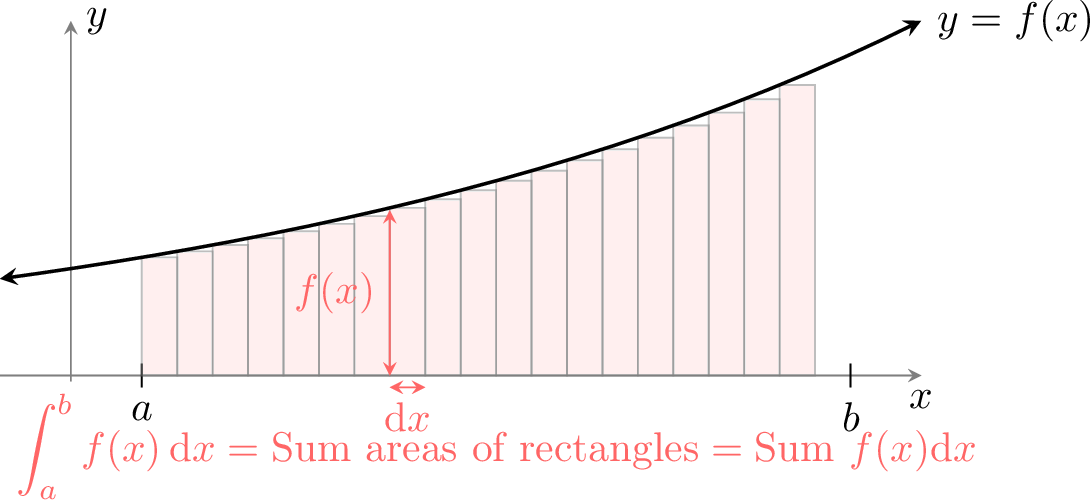

We aim to measure the shaded area, denoted \(\displaystyle\int_a^b f(x)\,\mathrm dx\), under the curve of a non-negative function \(y=f(x)\).

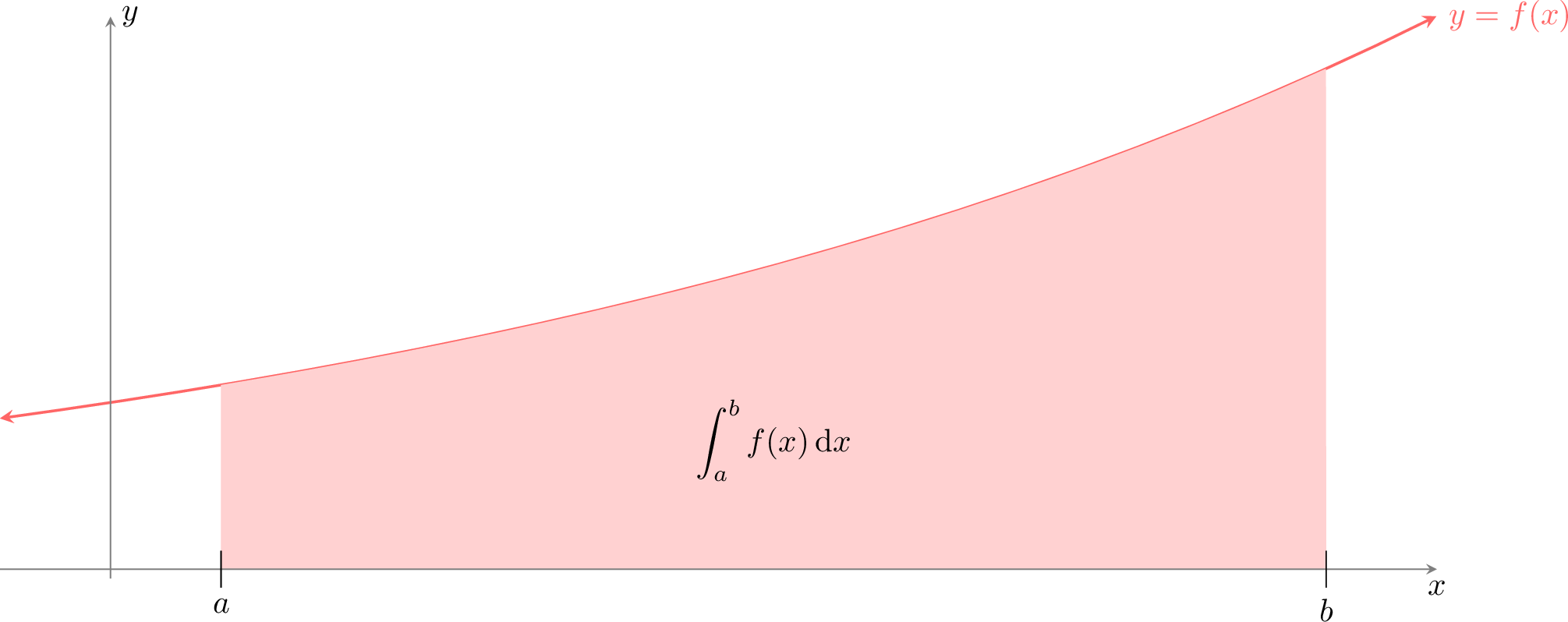

- Approximation with 1 rectangle: We can make a first, rough approximation by filling the area with a single rectangle of width \((b-a)\) and height \(f(a)\) (the value of the function at the left endpoint).

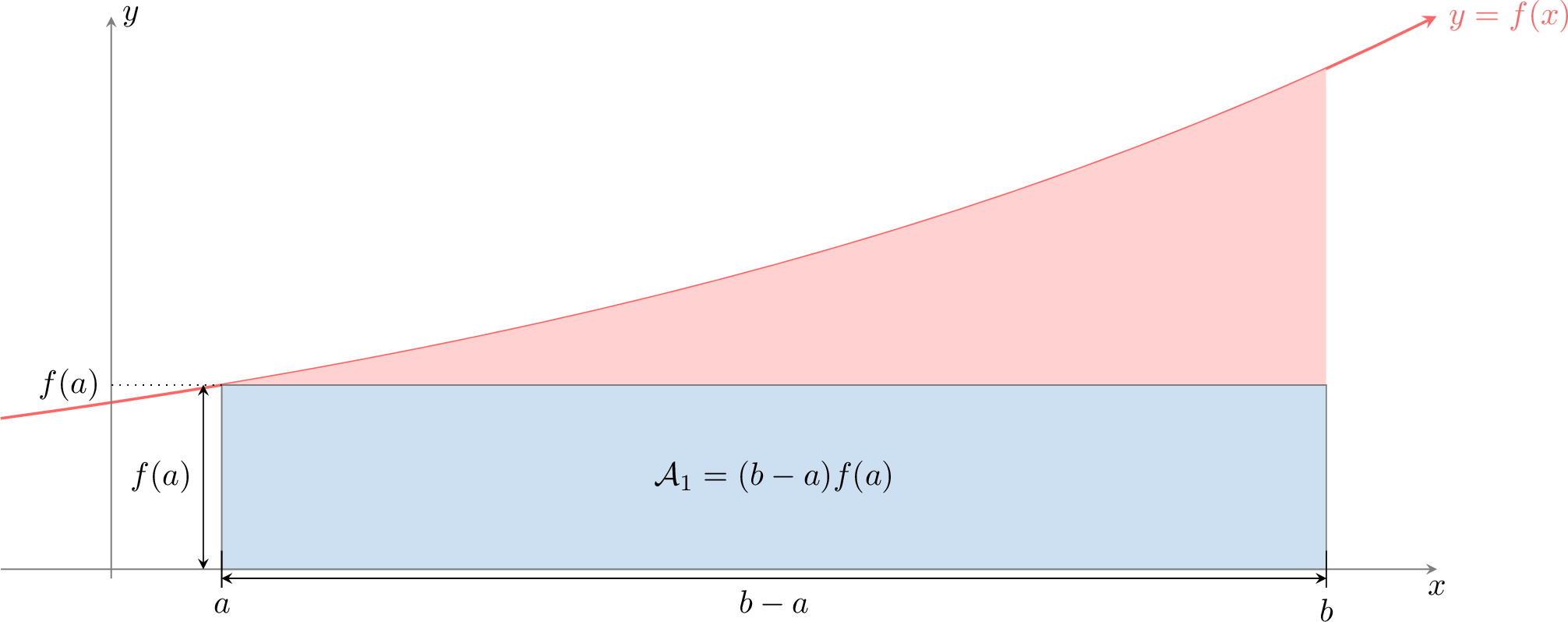

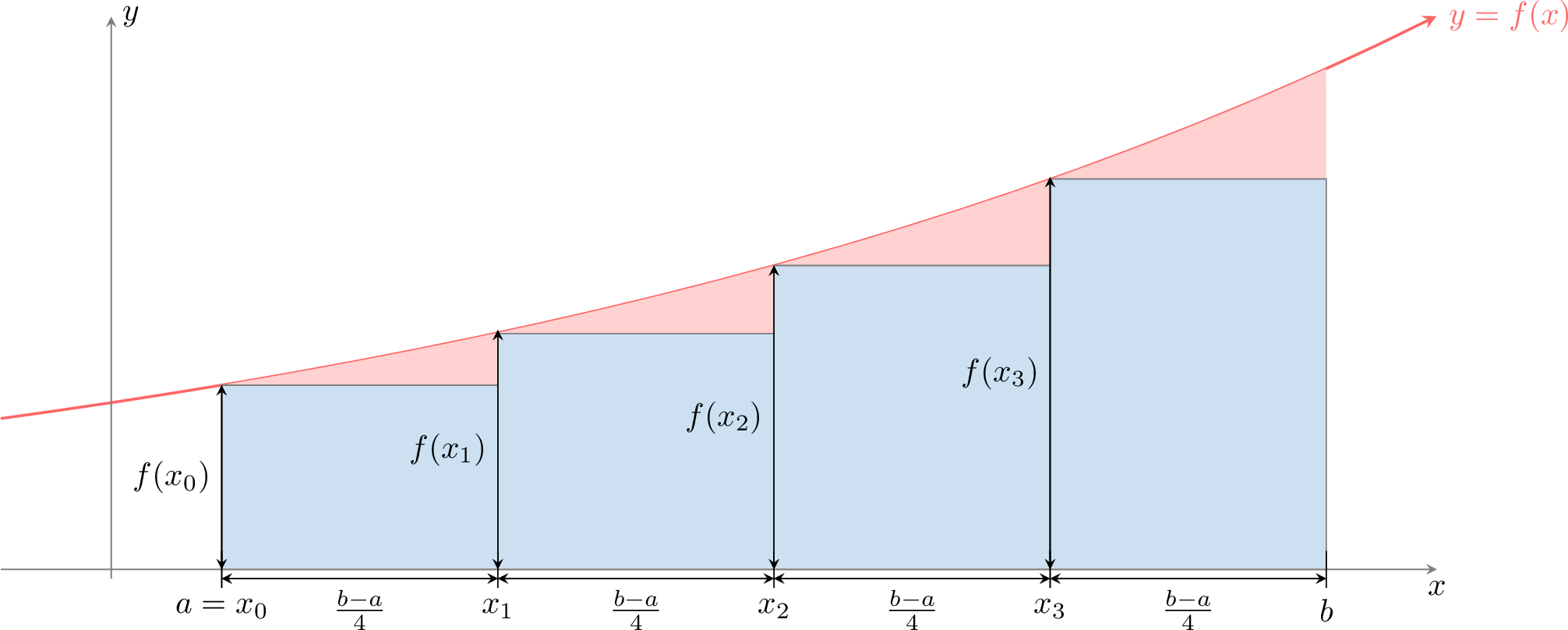

- Approximation with 4 rectangles: To improve the approximation, we divide the interval \([a,b]\) into 4 equal subintervals, each of width \(\frac{b-a}{4}\). We construct a rectangle on each subinterval, using the function's value at the left endpoint for the height.

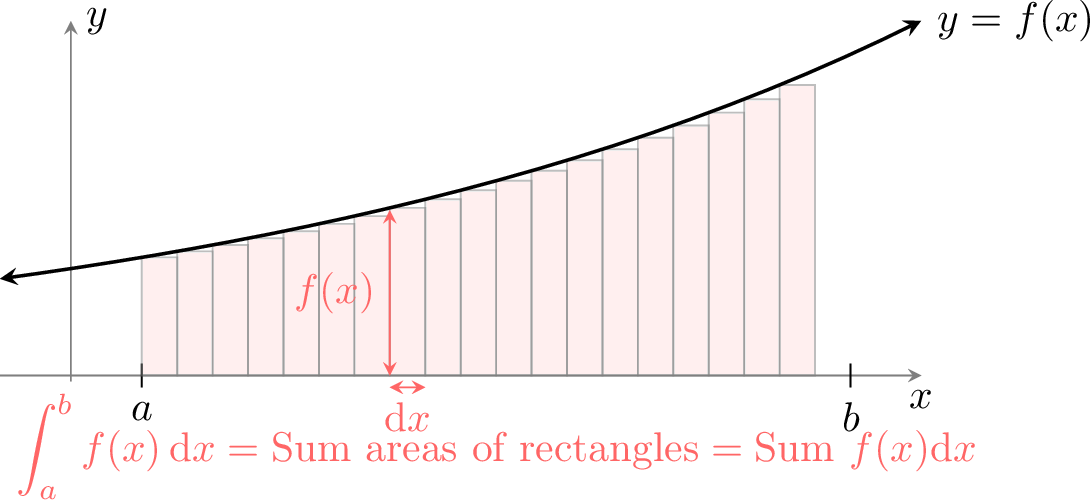

- Approximation with \(n\) rectangles: We can generalize this by dividing the interval into \(n\) equal subintervals, each of width \(\Delta x = \frac{b-a}{n}\). Let \(x_i=a+i\Delta x\) for \(i=0,1,\dots,n-1\). The sum of the areas of the \(n\) rectangles is:$$ S_n = \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} f(x_i) \Delta x. $$As we increase the number of rectangles (\(n \to \infty\)), the width of each rectangle becomes infinitesimally small, and the sum of their areas becomes a perfect match for the area under the curve:$$\displaystyle\int_a^b f(x)\,\mathrm dx = \lim_{n\to\infty} S_n.$$

Definition of the Definite Integral

Definition Definite Integral

The definite integral of a continuous function \(f\) from \(a\) to \(b\) is the limit of the Riemann sum as the number of subintervals approaches infinity. It is denoted by:$$ \int_a^b f(x)\,\mathrm dx = \lim_{n \to \infty} \sum_{i=0}^{n-1} f(x_i) \Delta x $$where the interval \([a,b]\) is divided into \(n\) subintervals of equal width \(\Delta x = \dfrac{b-a}{n}\) and \(x_i\) is a sample point in the \(i\)th subinterval.

- \(a\) and \(b\) are the limits of integration.

- \(f(x)\) is the integrand.

This notation, introduced by Leibniz, captures the idea of summing (\( \int \) is an elongated 'S' for summa) the areas of infinitely many rectangles of height \(f(x)\) and infinitesimal width \(dx\).

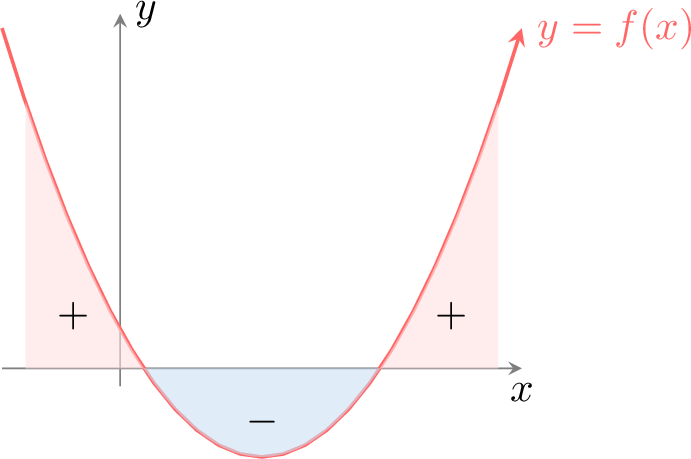

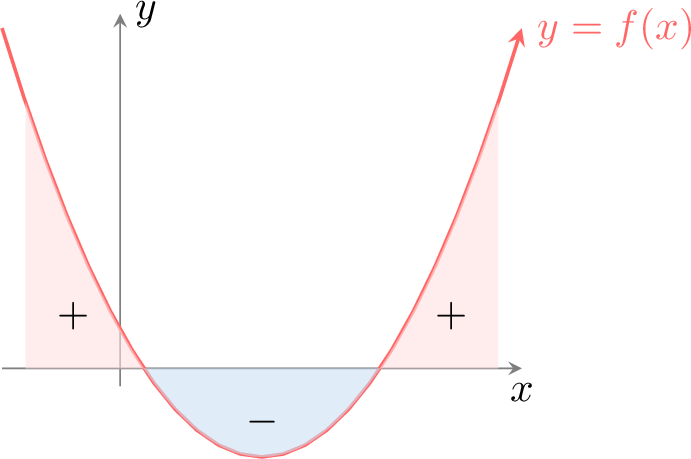

Definition Signed Area

The definite integral calculates the signed area.

- Area above the x-axis is counted as positive.

- Area below the x-axis is counted as negative.

Example

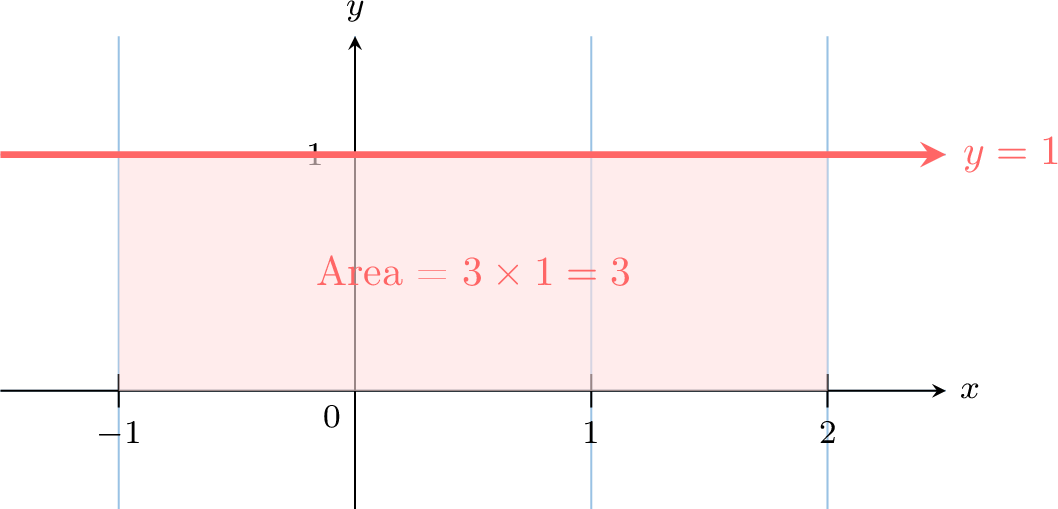

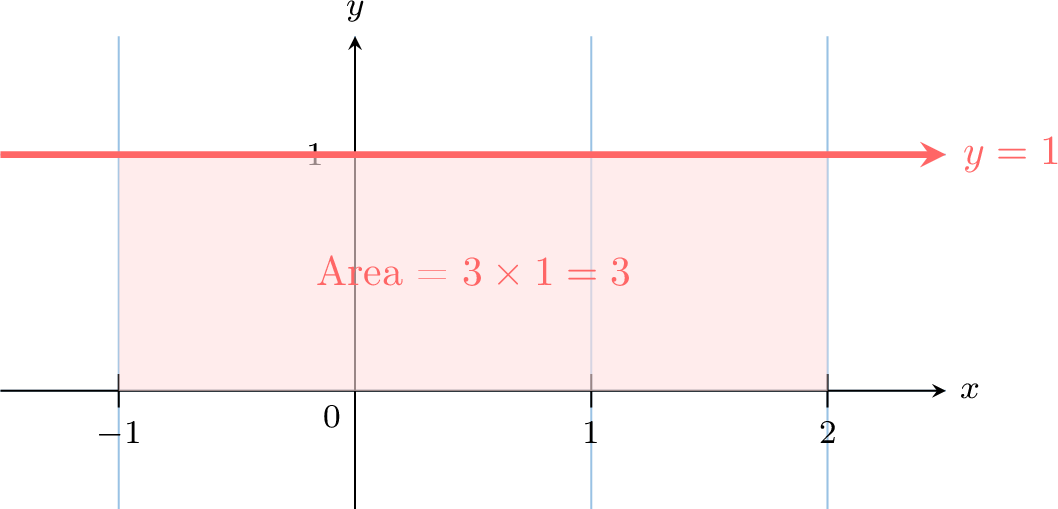

Determine the integral \(\displaystyle\int_{-1}^{2} 1\,\mathrm dx\) by interpreting it as an area.

The integral represents the area under the constant function \(f(x)=1\) from \(x=-1\) to \(x=2\). This forms a rectangle with width \(2 - (-1) = 3\) and height \(1\).

Properties of the Definite Integral

Proposition Properties of Integration

Let \(f\) and \(g\) be continuous functions and \(k\) be a constant.

- Zero-Width Interval:$$\displaystyle\int_a^a f(x) \;dx= 0.$$

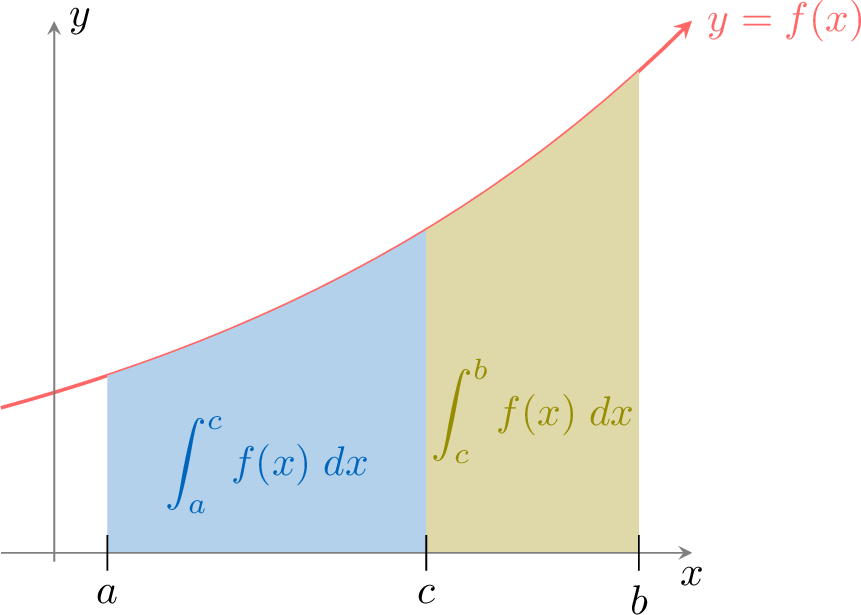

- Additivity of Intervals (Chasles's Relation): For any \(c\) between \(a\) and \(b\):$$\displaystyle\int_a^b f(x)\;dx = \int_a^c f(x) \; dx + \int_c^b f(x)\;dx$$

- Linearity:$$\displaystyle\int_a^b (f(x)+g(x)) \; dx= \int_a^b f(x) \; dx+ \int_a^b g(x) \; dx$$$$\displaystyle\int_a^b k f(x) \; dx= k \int_a^b f(x) \; dx.$$

The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

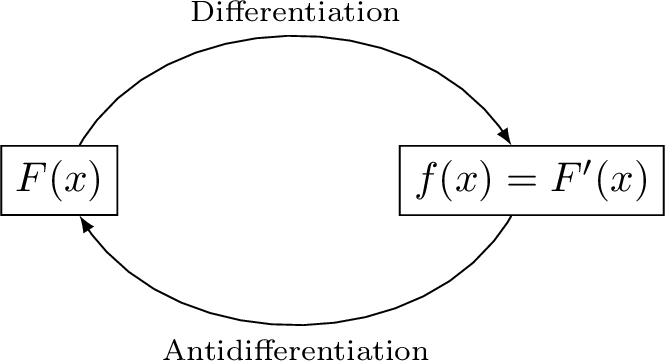

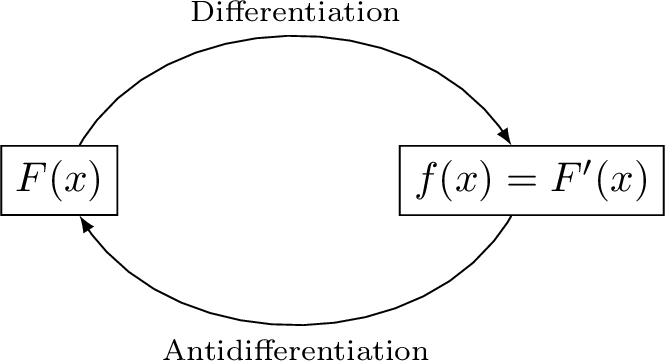

So far, we have defined the definite integral as the limit of a sum—a geometric concept of area. Separately, differentiation is a process of finding rates of change. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus provides a profound and powerful link between these two seemingly unrelated ideas: integration and differentiation are inverse processes of each other.

Antiderivatives

Definition Antiderivative

A function \(F\) is an antiderivative of a function \(f\) if \(F'(x) = f(x)\). The process of finding an antiderivative is called antidifferentiation or indefinite integration.

Since the derivative of a constant is zero, any function \(f\) does not have a unique antiderivative. For example, if \(F(x) = x^2\) is an antiderivative of \(f(x)=2x\), then \(G(x)=x^2+5\) is also an antiderivative, since \(G'(x) = 2x+0 = 2x\). All antiderivatives of a function differ only by a constant.

Definition Indefinite Integral

The family of all antiderivatives of a function \(f\) is called the indefinite integral of \(f\). It is denoted by:$$ \int f(x)\,\mathrm dx = F(x)+C $$where \(F\) is any particular antiderivative of \(f\) and \(C\) is an arbitrary constant called the constant of integration.

Finding Antiderivatives

The process of finding antiderivatives relies on reversing the rules of differentiation. Just as we have a table of derivatives for common functions, we can create a corresponding table of antiderivatives.

Proposition Antiderivatives of Common Functions

$$\begin{array}{|c|c|}\hline Function f(x) & An Antiderivative F(x) \\

\hline k \text{ (a constant)} & k x\\

\hline x^{n}, n \neq-1 & \dfrac{x^{n+1}}{n+1} \\

\hline e^{x} & e^{x} \\

\hline \frac{1}{x} & \ln|x| \\

\hline \cos(x) & \sin(x) \\

\hline \sin(x) & -\cos(x) \\

\hline\end{array}$$

This table is obtained by reading the table of standard derivatives in reverse.

Example

Find an antiderivative of \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x^2}\).

First, we rewrite the function using a negative exponent: \(f(x)=x^{-2}\).

An antiderivative of the power function \(f(x)=x^n\) (for \(n\neq -1\)) is \(F(x)=\dfrac{x^{n+1}}{n+1}\). With \(n=-2\), we have$$\begin{aligned} F(x) &= \frac{x^{-2+1}}{-2+1} \\ &= \frac{x^{-1}}{-1} \\ &= -\frac{1}{x}\end{aligned}$$

An antiderivative of the power function \(f(x)=x^n\) (for \(n\neq -1\)) is \(F(x)=\dfrac{x^{n+1}}{n+1}\). With \(n=-2\), we have$$\begin{aligned} F(x) &= \frac{x^{-2+1}}{-2+1} \\ &= \frac{x^{-1}}{-1} \\ &= -\frac{1}{x}\end{aligned}$$

Proposition Linearity of Integration

Let \(u\) and \(v\) be two functions with antiderivatives \(U\) and \(V\), and let \(k\) be a constant.

- An antiderivative of \(u+v\) is \(U+V\).

- An antiderivative of \(ku\) is \(kU\).

Example

Find an antiderivative of \(f(x)=2x+3\).

We use the linearity property to find the antiderivative of each term separately.

- An antiderivative of \(2x\) is \(2 \cdot \dfrac{x^2}{2} = x^2\).

- An antiderivative of \(3\) is \(3x\).

Proposition Antiderivatives of Composite Functions (Reverse Chain Rule)

Let \(u\) be a differentiable function of \(x\).$$\begin{array}{|c|c|}\hline Function f(x) & An Antiderivative F(x) \\

\hline u'(x) [u(x)]^n, \quad n \neq -1 & \dfrac{[u(x)]^{n+1}}{n+1} \\

\hline \dfrac{u'(x)}{u(x)} & \ln|u(x)| \\

\hline u'(x)e^{u(x)} & e^{u(x)} \\

\hline\end{array}$$

Example

Find an antiderivative of \(f(x)=\frac{2x}{x^2+1}\).

The function \(f(x)\) is of the form \(\dfrac{u'(x)}{u(x)}\).

Let \(u(x) = x^2+1\). Then its derivative is \(u'(x) = 2x\).

So, we can write \(f(x) = \dfrac{u'(x)}{u(x)}\).

From the table, an antiderivative is \(F(x) = \ln|u(x)|\).

Substituting back, we get \(F(x) = \ln|x^2+1|\). Since \(x^2+1\) is always positive, we can remove the absolute value bars:$$ F(x) = \ln(x^2+1) $$

Let \(u(x) = x^2+1\). Then its derivative is \(u'(x) = 2x\).

So, we can write \(f(x) = \dfrac{u'(x)}{u(x)}\).

From the table, an antiderivative is \(F(x) = \ln|u(x)|\).

Substituting back, we get \(F(x) = \ln|x^2+1|\). Since \(x^2+1\) is always positive, we can remove the absolute value bars:$$ F(x) = \ln(x^2+1) $$

Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

Theorem Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

If \(f\) is a continuous function on the interval \([a,b]\) and \(F\) is any antiderivative of \(f\), then:$$ \int_a^b f(x)\,\mathrm dx = F(b) - F(a) $$This result is often written using the notation \(\left[ F(x) \right]_a^b = F(b)-F(a)\).

The theorem states that integration and differentiation are inverse processes. We can understand this by examining the "area function".

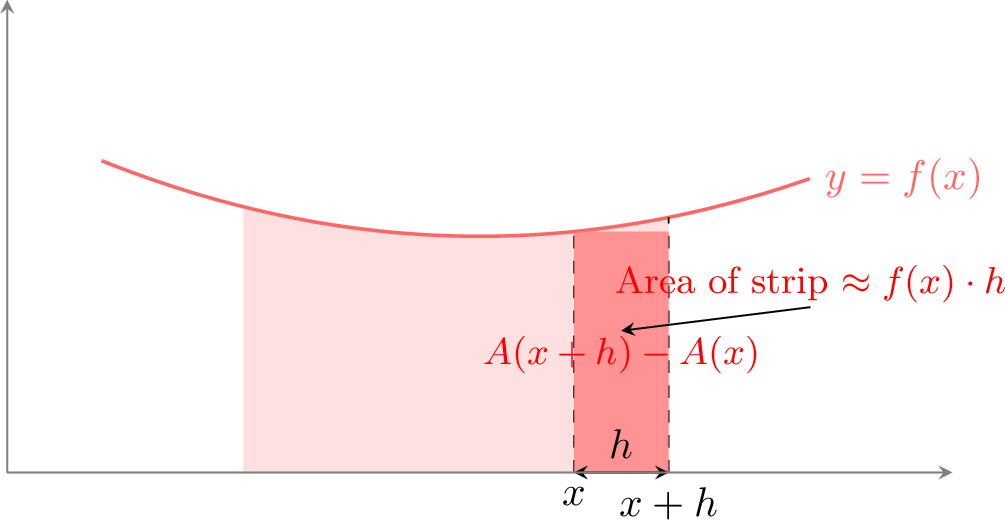

- Defining the Area Function: Let's define a function, \(A(x)\), as the area under the curve \(y=f(t)\) from a fixed starting point \(a\) to a variable endpoint \(x\): $$ A(x) = \int_a^x f(t) \, dt. $$ Our goal is to show that the derivative of this area function, \(A'(x)\), is simply the original function \(f(x)\).

- The Area of a Thin Strip: By its definition, the area of a thin vertical strip between \(x\) and \(x+h\) is the difference between the total area up to \(x+h\) and the total area up to \(x\): $$ \text{Area of strip} = A(x+h) - A(x). $$

- Approximating the Area of the Strip: As shown in the diagram, if the width \(h\) is very small, this thin strip is almost a perfect rectangle.

- The width of the rectangle is \(h\).

- The height of the rectangle is approximately \(f(x)\).

- Connecting to the Derivative: We now have two expressions for the area of the strip: $$ A(x+h) - A(x) \approx f(x) \cdot h. $$ Dividing both sides by \(h\), we get the difference quotient for the function \(A(x)\): $$ \frac{A(x+h) - A(x)}{h} \approx f(x). $$

- Taking the Limit: This approximation becomes a perfect equality as the width of the strip, \(h\), approaches zero. Taking the limit of both sides: $$ \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{A(x+h)-A(x)}{h} = f(x). $$ The expression on the left is, by definition, the derivative of the area function, \(A'(x)\): $$ A'(x) = f(x). $$

- Finding the Formula: Let \(F(x)\) be any antiderivative of \(f(x)\). Since all antiderivatives of a function differ only by a constant, we know that: $$ A(x) = F(x) + C $$ for some constant \(C\). To find \(C\), we can evaluate this at \(x=a\): $$ A(a) = \int_a^a f(t)\,dt = 0 $$ so $$ F(a) + C = 0 \implies C = -F(a). $$ Thus the area function is \(A(x) = F(x) - F(a)\).

To find the total area up to \(x=b\), we simply evaluate \(A(b)\): $$ \int_a^b f(x)\,dx = A(b) = F(b) - F(a). $$

Remark

This theorem is fundamental because it connects the geometric concept of area (the definite integral) with the algebraic process of antidifferentiation. It gives us a powerful method to calculate exact areas without using the limit of a Riemann sum.

Example

Find \(\displaystyle \int_0^2 x^2 \mathrm dx\).

- Find an antiderivative: An antiderivative of \(f(x)=x^2\) is \(F(x) = \dfrac{x^3}{3}\).

- Apply the Fundamental Theorem: $$\begin{aligned}\displaystyle \int_0^2 x^2 \mathrm dx &= \left[ \frac{x^3}{3} \right]_0^2\\ &= F(2) - F(0) \\ &=\frac{2^3}{3} -\frac{0^3}{3}\\ &=\frac{8}{3} - 0 = \frac{8}{3} \end{aligned}$$

Techniques for Integration

While we can integrate basic functions by reversing the rules of differentiation, many functions require more advanced techniques. This section covers two key methods that are the reverse of the chain rule and the product rule: integration by substitution and integration by parts.

Integration by Reverse Chain Rule

Method Integration by Inspection

A common strategy is to make an educated guess for the antiderivative, differentiate it, and adjust any constant factors. This is often called "integration by inspection" or "guess and check".

- Guess: Look at the function and guess a possible antiderivative.

- Differentiate: Differentiate your guess.

- Adjust: Compare your result with the original integrand and multiply by a constant factor to correct any discrepancies.

Example

Find the integral of \(\sin(3x)\).

- Guess: The integral of \(\sin\) is \(-\cos\). A good guess for the antiderivative is \(F(x) = -\cos(3x)\).

- Differentiate: Using the chain rule, the derivative of our guess is \(F'(x) = -(-\sin(3x)) \cdot 3 = 3\sin(3x)\).

- Adjust: Our result, \(3\sin(3x)\), is 3 times larger than the original integrand, \(\sin(3x)\). We must therefore divide our initial guess by 3.

Integration by Substitution

Integration by substitution is a powerful technique that reverses the chain rule for differentiation. It is used when an integrand contains both a function and its derivative.

Consider the integral \(\int (2x^3+1)^7 (6x^2) \, dx\). We can see that the expression contains an "inner function", \(u = 2x^3+1\), and its derivative, \(u'(x) = 6x^2\). This structure is a clear indicator for substitution.

Let's define a new variable, \(u = 2x^3+1\). Differentiating this with respect to \(x\) gives \(u'(x)=6x^2\). In differential form, we can write \(du = 6x^2\,dx\). Now we can substitute both \(u\) and \(du\) into the original integral:$$\begin{aligned} \int \underbrace{(2x^3+1)^{7}}_{u^{7}} \underbrace{(6x^2)\,dx}_{du} &= \int u^{7}\,du \\ &= \frac{1}{8}u^{8}+C\end{aligned}$$Finally, we substitute back to express the result in terms of \(x\):$$ \int (2x^3+1)^7 (6x^2) \, dx =\frac{1}{8}(2x^3+1)^{8}+C $$

Consider the integral \(\int (2x^3+1)^7 (6x^2) \, dx\). We can see that the expression contains an "inner function", \(u = 2x^3+1\), and its derivative, \(u'(x) = 6x^2\). This structure is a clear indicator for substitution.

Let's define a new variable, \(u = 2x^3+1\). Differentiating this with respect to \(x\) gives \(u'(x)=6x^2\). In differential form, we can write \(du = 6x^2\,dx\). Now we can substitute both \(u\) and \(du\) into the original integral:$$\begin{aligned} \int \underbrace{(2x^3+1)^{7}}_{u^{7}} \underbrace{(6x^2)\,dx}_{du} &= \int u^{7}\,du \\ &= \frac{1}{8}u^{8}+C\end{aligned}$$Finally, we substitute back to express the result in terms of \(x\):$$ \int (2x^3+1)^7 (6x^2) \, dx =\frac{1}{8}(2x^3+1)^{8}+C $$

Proposition Integration by Substitution

- Indefinite Integral:$$\int f(u(x))u'(x) \, dx = \int f(u) \, du $$

- Definite Integral:$$\int_a^b f(u(x))u'(x) \, dx = \int_{u(a)}^{u(b)} f(u) \, du $$

Example

Find \(\displaystyle\int_0^1 2x(x^2 + 1)^3\;dx\).

- Substitution: Let \(u = x^2+1\). Then \(du = 2x\,dx\).

- Change limits:

- When \(x=0\), \(u = 0^2+1=1\).

- When \(x=1\), \(u = 1^2+1=2\).

- Integrate: We substitute to get a simpler integral in terms of \(u\): $$\begin{aligned} \int_0^1 \underbrace{(x^2 + 1)^3}_{u^3} \underbrace{2x\;dx}_{du} &= \int_1^2 u^3 \, du \\ &= \left[\frac{u^4}{4}\right]_1^2 \\ &= \frac{2^4}{4} - \frac{1^4}{4} \\ &= 4 - \frac{1}{4}\\ &= \frac{15}{4} \end{aligned}$$

Integration by Parts

Integration by parts is a powerful technique for integrating the product of two functions. It is derived from the product rule for differentiation and effectively reverses it.

Proposition Integration by Parts

For two differentiable functions \(u(x)\) and \(v(x)\):

- Indefinite Integral: $$ \int u(x)v'(x) \, dx = u(x)v(x) - \int u'(x)v(x) \, dx $$

- Definite Integral: $$ \int_a^b u(x)v'(x) \, dx = \left[u(x)v(x)\right]_a^b - \int_a^b u'(x)v(x) \, dx $$

The product rule for differentiation states that for two functions \(u(x)\) and \(v(x)\):$$ \left(u(x)v(x)\right)' = u'(x)v(x) + u(x)v'(x) $$Integrating both sides with respect to \(x\):$$ \int \left(u(x)v(x)\right)' \, dx = \int u'(x)v(x) \, dx + \int u(x)v'(x) \, dx $$Since integration is the antiderivative, the left side simplifies to \(u(x)v(x)\):$$ u(x)v(x) = \int u'(x)v(x) \, dx + \int u(x)v'(x) \, dx $$Rearranging this equation gives the formula for integration by parts:$$ \int u(x)v'(x) \, dx = u(x)v(x) - \int u'(x)v(x) \, dx $$

Note

The key to using this method is to choose \(u\) and \(v'\) strategically. The goal is to select a \(u\) that becomes simpler when differentiated (e.g., a polynomial) and a \(v'\) that is easy to integrate. The new integral, \(\int u'v \, dx\), should be easier to solve than the original one.

Example

Find \(\displaystyle\int_0^1 x e^x \; dx\).

We have a product of two functions, \(x\) and \(e^x\). We choose \(u\) and \(v'\):

- Let \(u=x\) (since its derivative \(u'=1\) is simpler).

- Let \(v'=e^x\) (since its antiderivative \(v=e^x\) is easy to find).