Real Polynomials

Linear and quadratic functions are the first two members of a broader class of functions called polynomials. Polynomials are fundamental in mathematics and are used to model a vast range of phenomena, from the trajectory of a projectile to complex economic trends. In this chapter, we will explore the algebra of polynomials, including their operations, factors, roots, and key theorems that govern their behavior.

Definitions

Definition Polynomial

- A polynomial in the variable \(x\) is an algebraic expression of the form$$P(x)=a_nx^n+a_{n-1}x^{n-1}+\dots+a_1 x+a_0,$$where \(n\) is a non-negative integer and \(a_0, a_1, \dots, a_n\) are constants called the coefficients.

- A polynomial equation in \(x\) is an equation of the form$$a_nx^n+a_{n-1}x^{n-1}+\dots+a_1 x+a_0=0,$$with \(a_n\neq 0\) and \(n\ge 1\).

- A polynomial function is a function defined for all real numbers \(x\) by$$P(x)=a_nx^n+a_{n-1}x^{n-1}+\dots+a_1 x+a_0.$$

- The degree of the polynomial is the highest power of the variable \(x\) that has a non-zero coefficient; this exponent is \(n\).

- The leading coefficient is the coefficient of the term with the highest power, \(a_n\).

- The constant term is the coefficient without a variable, \(a_0\).

Example

For the polynomial function \(P(x)=2x^4+3x^2+5x+4\), find the degree, the leading coefficient, the coefficient of \(x\), and the constant term.

We can imagine the missing \(x^3\) term as \(0x^3\) and write$$P(x)=2x^4+0x^3+3x^2+5x+4.$$

- The degree is the highest power of the variable \(x\) with non-zero coefficient. Here, the highest power is 4.

- The leading coefficient is the coefficient of the term with the highest power, which is \(2x^4\). Therefore, the leading coefficient is 2.

- The coefficient of \(x\) is the constant multiplying the term \(x\) (or \(x^1\)). In this case, the term is \(5x\), so the coefficient is 5.

- The constant term is the term without a variable. Here, it is 4.

Definition Names of Low-Degree Polynomials

Polynomials of low degree have special names:

| Polynomial function | Degree | Name |

| \(ax+b, \quad a \neq 0\) | 1 | linear |

| \(ax^2+bx+c, \quad a \neq 0\) | 2 | quadratic |

| \(ax^3+bx^2+cx+d, \quad a \neq 0\) | 3 | cubic |

| \(ax^4+bx^3+cx^2+dx+e, \quad a \neq 0\) | 4 | quartic |

Definition Equality of Polynomials

Two polynomials are equal if the coefficients of each corresponding power of the variable are identical (that is, the coefficient of \(x^k\) is the same in both polynomials for every \(k\)).

This principle is fundamental as it allows us to find unknown constants by equating the coefficients of terms with the same power. This technique is known as identification of coefficients.

Example

Find the coefficients \(a\) and \(b\) given \(ax + b = 2x - 3\).

By equating the coefficients of corresponding powers of \(x\):

- The coefficients of the \(x\) term must be equal: \(a=2\).

- The constant terms must be equal: \(b=-3\).

Operations with Polynomials

Method Operations with Polynomials

Polynomials can be added, subtracted, and multiplied. The key principle for addition and subtraction is to combine like terms: terms that have the same power of the variable \(x\).

Example

For \(P(x) = 4x^3 + 2x^2 - 5x + 1\) and \(Q(x) = x^3 - 3x^2 + 7\), find:

- \(P(x) + Q(x)\)

- \(P(x) - Q(x)\)

- Addition: We group like terms. $$ \begin{aligned} P(x) + Q(x) &= (4x^3 + 2x^2 - 5x + 1) + (x^3 - 3x^2 + 7) \\ &= (4x^3 + x^3) + (2x^2 - 3x^2) - 5x + (1 + 7) \\ &= 5x^3 - x^2 - 5x + 8 \end{aligned} $$

- Subtraction: Be careful with the signs when distributing the negative. $$ \begin{aligned} P(x) - Q(x) &= (4x^3 + 2x^2 - 5x + 1) - (x^3 - 3x^2 + 7) \\ &= 4x^3 + 2x^2 - 5x + 1 - x^3 + 3x^2 - 7 \\ &= (4x^3 - x^3) + (2x^2 + 3x^2) - 5x + (1 - 7) \\ &= 3x^3 + 5x^2 - 5x - 6 \end{aligned} $$

Example

For \(P(x) = x^3 - 2x + 4\) and \(Q(x) = 2x^2 + 3x - 5\), find \(P(x)Q(x)\).

To multiply two polynomials, we multiply each term of the first polynomial by each term of the second polynomial.$$ \begin{aligned} P(x)Q(x) &= (x^3 - 2x + 4)(2x^2 + 3x - 5) \\

&= x^3(2x^2 + 3x - 5) - 2x(2x^2 + 3x - 5) + 4(2x^2 + 3x - 5) \\

&= (2x^5 + 3x^4 - 5x^3) - (4x^3 + 6x^2 - 10x) + (8x^2 + 12x - 20) \\

&= 2x^5 + 3x^4 - 5x^3 - 4x^3 - 6x^2 + 10x + 8x^2 + 12x - 20 \\

&= 2x^5 + 3x^4 - 9x^3 + 2x^2 + 22x - 20 \end{aligned} $$The degree of the product of two non-zero polynomials \(P(x)\) and \(Q(x)\) is the sum of their individual degrees. This is because the leading term of the product \(P(x)Q(x)\) is obtained by multiplying the leading term of \(P(x)\) by the leading term of \(Q(x)\), and when we multiply these terms, their exponents add.

In this specific case, since the degree of \(P(x)\) is 3 and the degree of \(Q(x)\) is 2, the degree of their product is \(3 + 2 = 5\).

In this specific case, since the degree of \(P(x)\) is 3 and the degree of \(Q(x)\) is 2, the degree of their product is \(3 + 2 = 5\).

The Division Algorithm

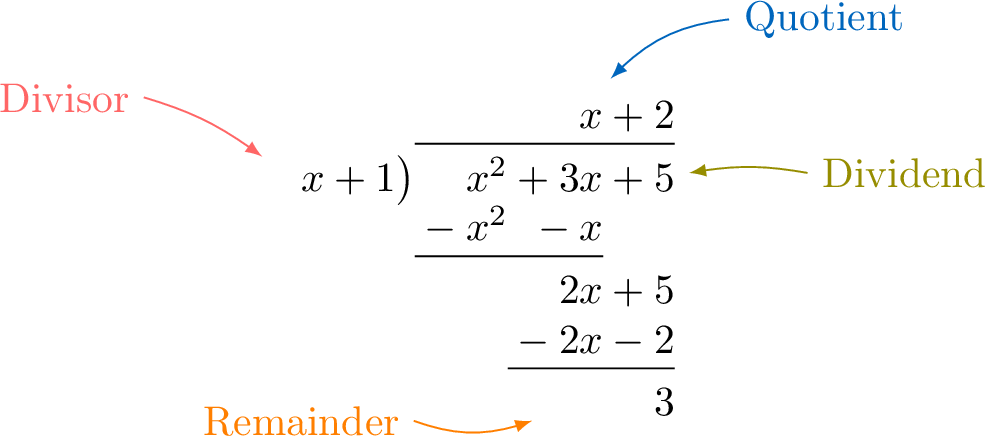

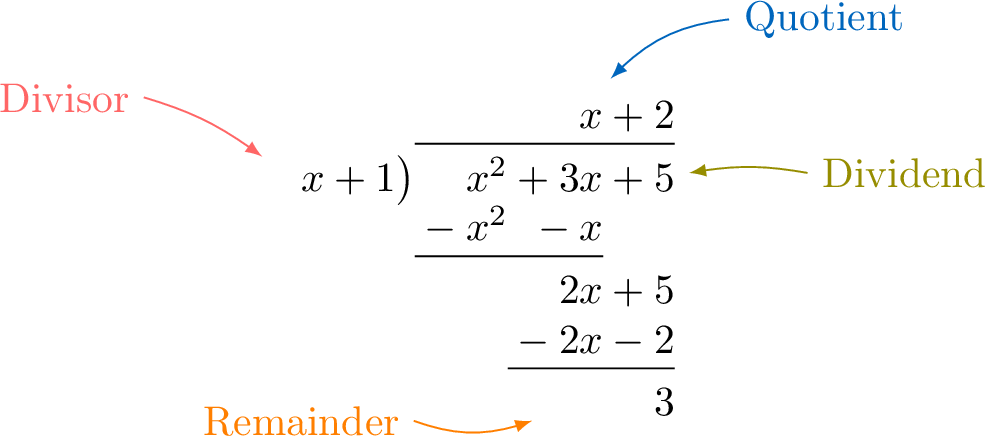

Proposition Division With Remainder

If a polynomial \(P\) is divided by a non-zero polynomial \(D\), then there exist unique polynomials \(Q\) and \(R\) such that$$ P = DQ + R \quad \text{with } \deg(R)<\deg(D). $$Here \(P\) is the dividend, \(D\) is the divisor, \(Q\) is the quotient, and \(R\) is the remainder. The remainder \(R\) may be the zero polynomial.

Method Division Algorithm

The division of one polynomial by another can be performed using a long division algorithm, which is analogous to the method used for dividing integers.

Example

$$\begin{array}{ccccccccl} \textcolor{olive}{x^2+3x+5} &=& \textcolor{colordef}{(x+1)}& \times& \textcolor{colorprop}{(x+2)}&+&\textcolor{orange}{3} & \text{ with }& \deg(\textcolor{orange}{3})\lt \deg(\textcolor{colordef}{x+1})\\

\textcolor{olive}{\text{Dividend}}&=& \textcolor{colordef}{\text{Divisor}}&\times&\textcolor{colorprop}{\text{Quotient}}&+&\textcolor{orange}{\text{Remainder}}& \text{ with }& \deg(\textcolor{orange}{\text{Remainder}})\lt \deg(\textcolor{colordef}{\text{Divisor}}) \end{array} $$

The Division Algorithm describes the result of any polynomial division. A special and important case is when the division is exact, meaning there is no remainder (\(R=0\)). This leads to the concept of a divisor, or factor.

Definition Divisor of a Polynomial

Let \(P\) and \(D\) be polynomials. We say that \(D\) divides \(P\) if there exists a polynomial \(Q\) such that$$ P(x) = D(x)Q(x). $$In this case, \(D\) is called a divisor or a factor of \(P\).

Proposition Condition for Divisibility

A polynomial \(D\) is a divisor of a polynomial \(P\) if and only if the remainder of the division of \(P\) by \(D\) is the zero polynomial (\(R=0\)).

We must prove both directions of the statement.

- (\(\Rightarrow\)): If \(D\) is a divisor of \(P\), then the remainder is zero.

Assume that \(D\) is a divisor of \(P\).

By the definition of a divisor, this means there exists a polynomial \(Q\) such that$$ P(x) = D(x)Q(x). $$This can be rewritten as \(P(x) = D(x)Q(x) + 0\).

By the Division Algorithm, there is a unique quotient and remainder. Comparing this with the standard form \(P(x) = D(x)Q(x) + R(x)\), we can see by uniqueness that the remainder \(R(x)\) must be \(0\). - (\(\Leftarrow\)): If the remainder is zero, then \(D\) is a divisor of \(P\).

Assume that the remainder of the division of \(P\) by \(D\) is zero.

By the Division Algorithm, we can write$$ P(x) = D(x)Q(x) + R(x). $$Substituting \(R(x)=0\) into this equation, we get$$ \begin{aligned} P(x) &= D(x)Q(x) + 0 \\ &= D(x)Q(x). \end{aligned} $$This is precisely the definition of \(D\) being a divisor of \(P\).

The Remainder and Factor Theorems

While the Division Algorithm applies to any polynomial divisor, two powerful theorems emerge when we consider the specific case of dividing by a linear polynomial of the form \((x-k)\).

Proposition The Remainder Theorem

When a polynomial \(P\) is divided by a linear polynomial of the form \((x-k)\), the remainder is the constant value \(P(k)\).

From the Division Algorithm, when a polynomial \(P(x)\) is divided by the divisor \(D(x) = x-k\), there exists a unique quotient \(Q(x)\) and a remainder \(R(x)\) such that$$ P(x) = (x-k)Q(x) + R(x). $$We know that the degree of the remainder must be less than the degree of the divisor. Since the degree of the divisor \((x-k)\) is \(1\), the degree of the remainder \(R\) must be \(0\). This means that the remainder is a constant; let's call this constant \(r\).

The division equation can therefore be written as$$ P(x) = (x-k)Q(x) + r. $$This identity is true for all values of \(x\). If we substitute \(x=k\) into the equation, we get$$ \begin{aligned} P(k) &= (k-k)Q(k) + r \\ &= 0 \cdot Q(k) + r \\ &= r. \end{aligned} $$Thus, the remainder \(r\) is precisely the value of the polynomial when evaluated at \(k\): \(r=P(k)\).

The division equation can therefore be written as$$ P(x) = (x-k)Q(x) + r. $$This identity is true for all values of \(x\). If we substitute \(x=k\) into the equation, we get$$ \begin{aligned} P(k) &= (k-k)Q(k) + r \\ &= 0 \cdot Q(k) + r \\ &= r. \end{aligned} $$Thus, the remainder \(r\) is precisely the value of the polynomial when evaluated at \(k\): \(r=P(k)\).

Definition Root

Let \(P\) be a polynomial.

A number \(\alpha\) is a root (or zero) of \(P\) if \(P(\alpha)=0\).

A number \(\alpha\) is a root (or zero) of \(P\) if \(P(\alpha)=0\).

Proposition The Factor Theorem

For any polynomial \(P\), \((x-\alpha)\) is a factor of \(P\) if and only if \(P(\alpha)=0\).

Let \(P(x)\) be a polynomial and \(\alpha\) be a number.$$\begin{array}{rll} & (x-\alpha) \text{ is a factor of } P(x) & \\

\iff & \text{the remainder of the division of } P(x) \text{ by } (x-\alpha) \text{ is } 0 & \text{(by the Condition for Divisibility)} \\

\iff & P(\alpha) = 0 & \text{(by the Remainder Theorem, since the remainder is } P(\alpha))\end{array}$$

Quadratic Equations with Complex Roots

The Factor Theorem connects roots to factors, but it does not guarantee that a real polynomial has any real roots (for example, \(P(x)=x^2+1\)). To fully understand the roots of all polynomials, we must consider solutions in the set of complex numbers, \(\mathbb{C}\).

Proposition Solving equations of the form \(x^2 \equal k\)

Consider the equation \(x^2=k\) where \(k\) is a real number.

- If \(k \ge 0\), the equation has two real roots: \(x = \sqrt{k}\) and \(x = -\sqrt{k}\) (these are equal if \(k=0\)).

- If \(k < 0\), the equation has two purely imaginary roots: \(x = i\sqrt{|k|}\) and \(x = -i\sqrt{|k|}\).

Proposition The Quadratic Formula for Complex Roots

Consider the equation \(ax^2+bx+c=0\), with real coefficients \(a, b, c\) and \(a \neq 0\).

Let \(\Delta=b^2-4ac\) be the discriminant.

Let \(\Delta=b^2-4ac\) be the discriminant.

- If \(\Delta \ge 0\), the equation has real roots given by the standard quadratic formula.

- If \(\Delta < 0\), the equation has two complex conjugate roots: $$x = \frac{-b \pm i\sqrt{-\Delta}}{2a}.$$

The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra

Proposition The Fundamental Theorem of Algebra

Every non-constant polynomial of degree \(n \ge 1\) with complex (in particular, real) coefficients has exactly \(n\) roots in the set of complex numbers \(\mathbb{C}\), provided that roots are counted with their multiplicity.

Note

The proof of this theorem is beyond the scope of this course, but its result is fundamental. It guarantees that we do not need to invent new number systems to solve polynomial equations; the complex numbers are algebraically closed in this respect.

Proposition Conjugate Root Theorem

If a polynomial \(P(x)\) has real coefficients, and if \(z_0\) is a complex root of the equation \(P(x)=0\), then its conjugate, \(\conjugate{z_0}\), must also be a root.

Let \(P(x) = a_n x^n + \dots + a_1 x + a_0\) where all coefficients \(a_k\) are real numbers.

We assume that \(z_0\) is a root, so \(P(z_0) = 0\). We want to show that \(P(\conjugate{z_0})=0\).$$\begin{aligned} P(\conjugate{z_0}) &= a_n(\conjugate{z_0})^n + \dots + a_1\conjugate{z_0} + a_0 \\ &= a_n\conjugate{z_0^n} + \dots + a_1\conjugate{z_0} + a_0 && \text{(conjugate of a power)} \\ &= \conjugate{a_n}\conjugate{z_0^n} + \dots + \conjugate{a_1}\conjugate{z_0} + \conjugate{a_0} && \text{(coefficients \(a_k\) are real)} \\ &= \conjugate{a_n z_0^n} + \dots + \conjugate{a_1 z_0} + \conjugate{a_0} && \text{(conjugate of a product)} \\ &= \conjugate{a_n z_0^n + \dots + a_1 z_0 + a_0} && \text{(conjugate of a sum)} \\ &= \conjugate{P(z_0)} \\ &= \conjugate{0} = 0.\end{aligned}$$Thus, if \(z_0\) is a root, then \(\conjugate{z_0}\) must also be a root.

We assume that \(z_0\) is a root, so \(P(z_0) = 0\). We want to show that \(P(\conjugate{z_0})=0\).$$\begin{aligned} P(\conjugate{z_0}) &= a_n(\conjugate{z_0})^n + \dots + a_1\conjugate{z_0} + a_0 \\ &= a_n\conjugate{z_0^n} + \dots + a_1\conjugate{z_0} + a_0 && \text{(conjugate of a power)} \\ &= \conjugate{a_n}\conjugate{z_0^n} + \dots + \conjugate{a_1}\conjugate{z_0} + \conjugate{a_0} && \text{(coefficients \(a_k\) are real)} \\ &= \conjugate{a_n z_0^n} + \dots + \conjugate{a_1 z_0} + \conjugate{a_0} && \text{(conjugate of a product)} \\ &= \conjugate{a_n z_0^n + \dots + a_1 z_0 + a_0} && \text{(conjugate of a sum)} \\ &= \conjugate{P(z_0)} \\ &= \conjugate{0} = 0.\end{aligned}$$Thus, if \(z_0\) is a root, then \(\conjugate{z_0}\) must also be a root.

Example

Given that \(x = 2+i\) is a root of the polynomial equation \(P(x) = x^3 - 7x^2 + 17x - 15 = 0\), find all roots.

Let the roots be \(r_1, r_2, r_3\). We are given \(r_1 = 2+i\).

- Step 1: Apply the Conjugate Root Theorem. The coefficients of \(P(x)\) are real. Since \(r_1 = 2+i\) is a root, its conjugate \(r_2 = 2-i\) must also be a root.

- Step 2: Form a real quadratic factor. The quadratic factor corresponding to these two roots is \((x - r_1)(x - r_2)\). $$ \begin{aligned} (x - (2+i))(x - (2-i)) &= ((x-2) - i)((x-2) + i)\\ &= (x-2)^2 - i^2 \\ &= x^2 - 4x + 4 - (-1) \\ &= x^2 - 4x + 5. \end{aligned} $$

- Step 3: Find the remaining factor. Since \(P(x)\) is cubic, the remaining factor must be linear. We can write \(P(x) = (x^2 - 4x + 5)(x-k)\). Comparing the constant terms gives $$5 \times (-k) = -15,$$which implies \(k=3\). The third root is therefore \(r_3=3\).

Sum and Product of Roots Theorem

There is a direct and powerful relationship between the roots of a polynomial equation and its coefficients. We can discover this relationship by comparing the standard form of a polynomial with its factored form.

- Case 1: Quadratic Equation (\(n=2\))

Consider a monic quadratic equation (\(a_2=1\)) with roots \(r_1\) and \(r_2\).$$ \begin{aligned} x^2 + a_1x + a_0 &= (x-r_1)(x-r_2) \\ &= x^2 - (r_1+r_2)x + (r_1r_2).\end{aligned} $$By equating coefficients, we see:- The sum of the roots is \(r_1+r_2 = -a_1\).

- The product of the roots is \(r_1r_2 = a_0\).

- Case 2: Cubic Equation (\(n=3\))

Consider a monic cubic equation (\(a_3=1\)) with roots \(r_1, r_2, r_3\).$$ \begin{aligned} x^3 + a_2x^2 + a_1x + a_0 &= (x-r_1)(x-r_2)(x-r_3) \\ &= [x^2 - (r_1+r_2)x + r_1r_2](x-r_3) \\ &= x^3 - (r_1+r_2+r_3)x^2 + (r_1r_2+r_1r_3+r_2r_3)x - (r_1r_2r_3).\end{aligned} $$By equating coefficients, we see:- The sum of the roots is \(r_1+r_2+r_3 = -a_2\).

- The product of the roots is \(r_1r_2r_3 = -a_0\).

Proposition Vieta's Formulas

For a polynomial equation$$P(x) = a_nx^n + a_{n-1}x^{n-1} + \dots + a_1x + a_0 = 0,$$with roots \(\alpha_1, \alpha_2, \dots, \alpha_n\) (in \(\mathbb{C}\)):

- The sum of the roots is $$\sum_{i=1}^n \alpha_i = -\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_n}.$$

- The product of the roots is $$\prod_{i=1}^n \alpha_i = (-1)^n \frac{a_0}{a_n}.$$

Example

Find the sum and product of the roots of \(2x^3 - 7x^2 + 8x - 1 = 0\).

The polynomial is of degree \(n=3\). The coefficients are \(a_3=2, a_2=-7, a_1=8, a_0=-1\).

- Sum of roots: $$ -\frac{a_{n-1}}{a_n} = -\frac{a_2}{a_3} = -\frac{-7}{2} = \frac{7}{2}. $$

- Product of roots: $$ (-1)^n \frac{a_0}{a_n} = (-1)^3 \frac{a_0}{a_3} = (-1)\frac{-1}{2} = \frac{1}{2}. $$