Differential Equations

Many of the most important laws of nature, from the motion of planets to the growth of populations, are described not by simple formulas but by equations that relate a function to its rates of change. These are known as differential equations. They form the language of modern science and engineering.

In this chapter, we will learn what differential equations are and explore several fundamental techniques for finding their solutions. We will begin with analytical methods for exact solutions, such as separation of variables. We will then investigate numerical methods, like Euler's method, which allow us to approximate solutions when exact ones are out of reach.

In this chapter, we will learn what differential equations are and explore several fundamental techniques for finding their solutions. We will begin with analytical methods for exact solutions, such as separation of variables. We will then investigate numerical methods, like Euler's method, which allow us to approximate solutions when exact ones are out of reach.

Fundamentals of Differential Equations

Definition Differential Equation

A differential equation is an equation that contains an unknown function and one or more of its derivatives.

- The order of a differential equation is the order of the highest derivative it contains.

- A general solution is a family of functions that satisfies the equation, typically involving one or more arbitrary constants.

- An initial condition is a specified value of the function or its derivatives at a particular point.

- A particular solution is a specific solution. It can be obtained by using an initial condition to determine the values of the arbitrary constants in the general solution.

Example

An apple is dropped from rest at a height of 10 meters. Its vertical position, \(y(t)\), is governed by the second-order differential equation:$$\frac{d^2 y}{dt^2}=-g$$where \(g\) is the constant of gravitational acceleration.

- State the initial conditions for position \(y(0)\) and velocity \(y'(0)\).

- Verify that the general solution to this equation is \(y(t) = -\frac{1}{2}gt^2 + At + B\).

- Use the initial conditions to find the particular solution for the apple's motion.

- Initial Conditions:

- The initial height is 10 meters, so \(y(0)=10\).

- The apple is dropped ``from rest,'' so its initial velocity is zero. Thus, \(y'(0)=0\).

- Verifying the General Solution: We need to show that the second derivative of \(y(t) = -\frac{1}{2}gt^2 + At + B\) is equal to \(-g\).

- First derivative (velocity): \(y'(t) = \dfrac{d}{dt}\left(-\frac{1}{2}gt^2 + At + B\right) = -gt + A\).

- Second derivative (acceleration): \(y''(t) = \dfrac{d}{dt}(-gt + A) = -g\).

- Finding the Particular Solution: We apply the initial conditions to the general solution and its first derivative.

- Using \(y(0)=10\): $$ y(0) = -\frac{1}{2}g(0)^2 + A(0) + B \implies 10 = B $$

- Using \(y'(0)=0\): $$ y'(0) = -g(0) + A \implies 0 = A $$

Slope Fields

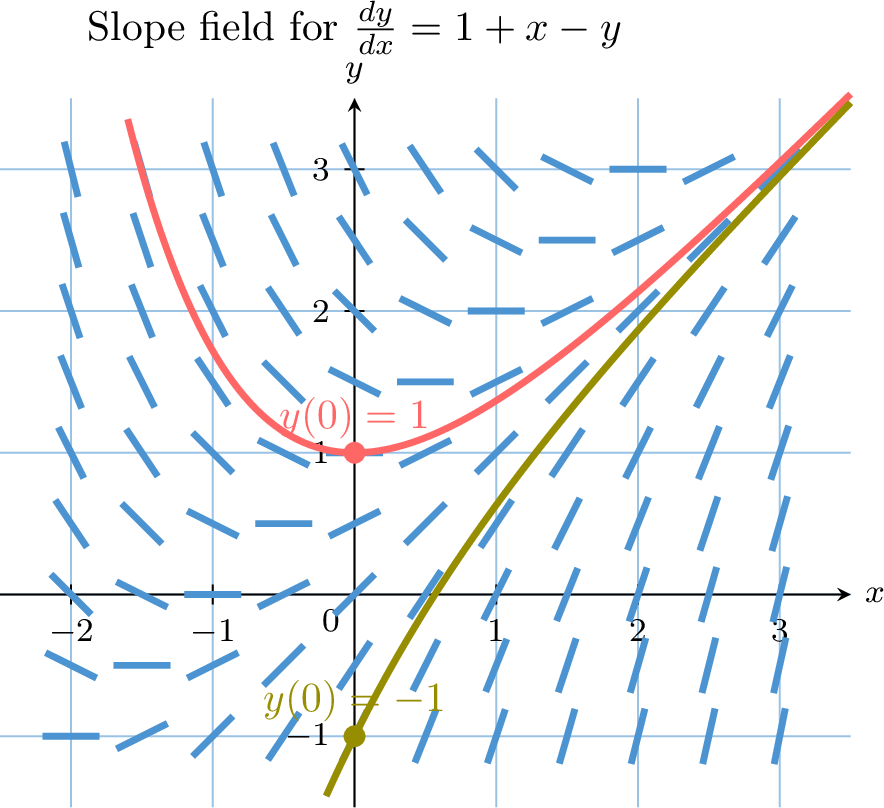

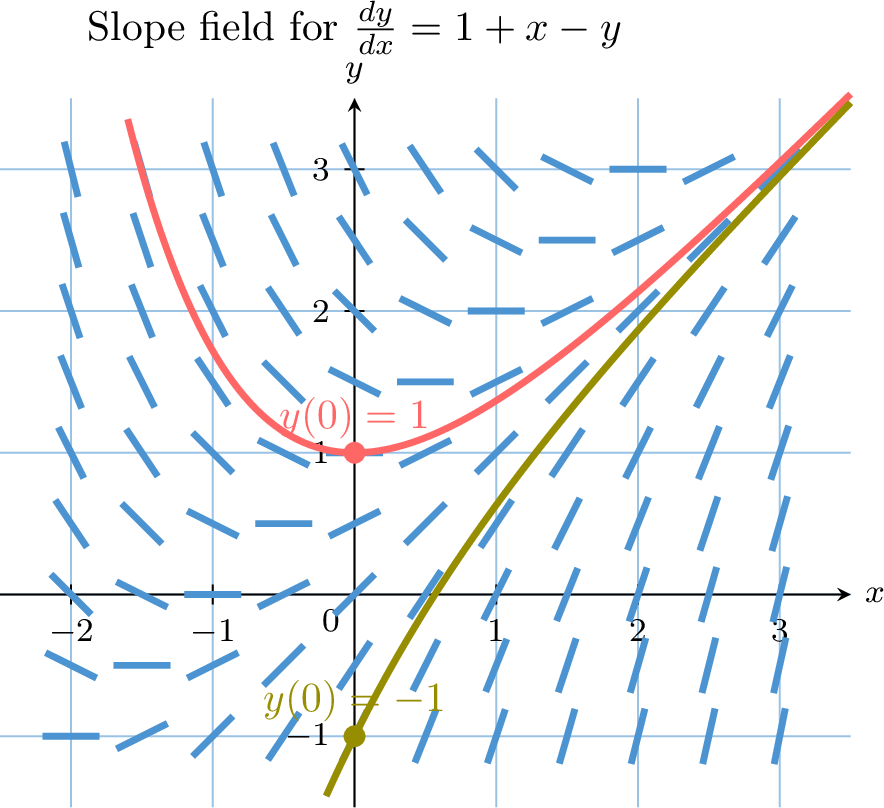

While algebraic techniques give us formulas for solutions, a geometric approach can give us a powerful intuition for how solutions behave. A differential equation of the form \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = f(x, y)\) is a machine that gives us the slope of a solution curve at any point \((x,y)\) in the plane.

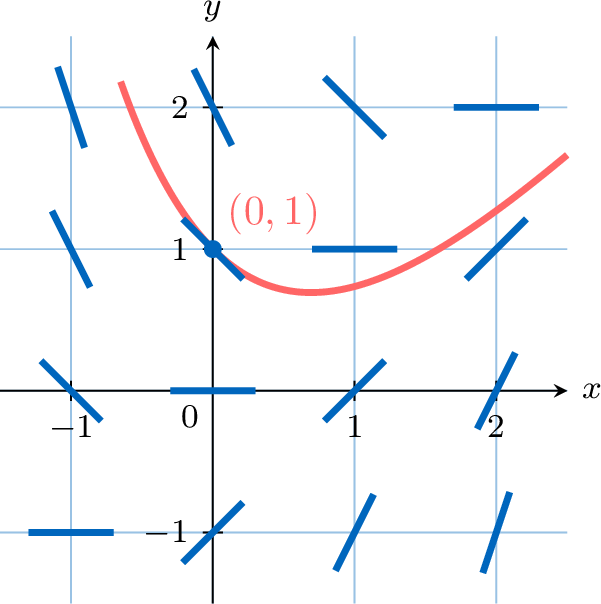

A slope field (or direction field) is a graphical representation of this information. At each point on a grid, we draw a small line segment with the slope given by the differential equation. The resulting field of slopes acts like a set of ``currents'' in a river. Any particular solution to the differential equation is a curve that ``flows'' along these currents, always tangent to the slope markers it passes through.

A slope field (or direction field) is a graphical representation of this information. At each point on a grid, we draw a small line segment with the slope given by the differential equation. The resulting field of slopes acts like a set of ``currents'' in a river. Any particular solution to the differential equation is a curve that ``flows'' along these currents, always tangent to the slope markers it passes through.

Method Sketching a Slope Field

To sketch a slope field for \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = f(x, y)\):

- Choose grid points: Select a representative set of integer points \((x, y)\) in the desired viewing window.

- Calculate slopes: For each point, calculate the value of the slope \(m = f(x, y)\). Organize these values in a table.

- Sketch segments: At each grid point, draw a short line segment with the calculated slope.

Example

For the differential equation \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = x-y\):

- Sketch the slope field for integer coordinates where \(-1 \le x \le 2\) and \(-1 \le y \le 2\).

- On your sketch, draw the particular solution curve that passes through the point \((0,1)\).

- Sketching the field: We first calculate the slopes \(m=x-y\) at each integer point in the grid.

\(\begin{aligned} & x\\ y \end{aligned} \) -1 0 1 2 2 -3 -2 -1 0 1 -2 -1 0 1 0 -1 0 1 2 -1 0 1 2 3 - Drawing the solution curve: Starting at the initial point \((0,1)\), we follow the direction of the slope field. The curve will be tangent to the line segments as it passes through the field.

Solving by Direct Integration

Method Solving for \(\frac{dy}{dx} \equal f(x)\)

When the derivative of a function depends only on \(x\), we can find the general solution by rearranging the equation and integrating directly.$$\begin{aligned}\frac{dy}{dx} &= f(x)\\

dy &= f(x)\, dx \\

\int dy &= \int f(x) \, dx \\

y &= \int f(x) \, dx + C\end{aligned}$$

Example

Find the general solution to \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = 3x^2 \) and the particular solution with initial condition \(y(0)=4\).

We rearrange and integrate both sides:$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{dy}{dx} &= 3x^2 \\

dy &= 3x^2 \, dx \\

\int dy &= \int 3x^2\, dx \\

y & = x^3 + C\end{aligned}$$This is the general solution. Now we use the initial condition \(y(0)=4\):$$ 4 = (0)^3 + C \implies C=4 $$The particular solution is \(y = x^3 + 4\).

Solving by Separation of Variables

A separable differential equation is one that can be expressed in the form \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = g(x)h(y)\). These equations can be solved by algebraically separating the variables before integrating.

Method Solving Separable Equations \(\frac{dy}{dx} \equal g(x)h(y)\)

This method applies when the equation can be rearranged so that all terms involving \(y\) are on one side and all terms involving \(x\) are on the other.

- Separate: Rearrange the equation into the form \(\dfrac{1}{h(y)}\, dy = g(x)\, dx\).

- Integrate: Integrate both sides of the equation with respect to their respective variables:$$ \int \dfrac{1}{h(y)} \, dy = \int g(x) \, dx $$

- Solve for \(y\): If possible, solve the resulting equation for \(y\) to get an explicit solution.

Example

Solve \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = -2xy^2\) with the initial condition \(y(1)=1\).

We rearrange and integrate both sides:$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{dy}{dx} &= -2xy^2 \\

\frac{1}{y^2} \, dy &= -2x \, dx \\

\int \frac{1}{y^2} \, dy &= \int -2x \, dx \\

\int y^{-2} \, dy &= \int -2x \, dx \\

-y^{-1} &= -x^2 + C \\

-\frac{1}{y} &= -x^2 + C\end{aligned}$$This is the general solution in implicit form. Using the initial condition \(y(1)=1\):$$ -\dfrac{1}{1} = -(1)^2 + C \implies -1 = -1 + C \implies C = 0 $$Substituting \(C=0\) gives the particular solution:$$ -\dfrac{1}{y} = -x^2 \implies y = \dfrac{1}{x^2} $$

Approximating Solutions with Euler's Method

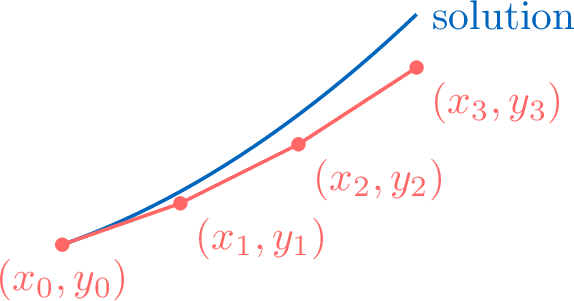

When a differential equation cannot be solved analytically, we can approximate its solution using numerical methods. Euler's method is the simplest of these, using linear approximation to step along the solution curve.

The method begins with an initial condition \((x_0, y_0)\) and proceeds in steps. Let's define a small, constant step size, \(h\). The \(x\)-coordinate of each subsequent point is found by adding this step size: \(x_{n+1} = x_n + h\).

The core of the method is to approximate the derivative \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\) using the gradient of the line segment connecting two consecutive points, \((x_n, y_n)\) and \((x_{n+1}, y_{n+1})\):$$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} \text{ at } (x_n, y_n) \approx \dfrac{y_{n+1} - y_n}{x_{n+1} - x_n} = \dfrac{y_{n+1} - y_n}{h}. $$Since the differential equation gives us the exact value of the derivative, \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = f(x_n, y_n)\), we can set these equal:$$ \dfrac{y_{n+1} - y_n}{h}\approx f(x_n, y_n). $$Rearranging this formula to find the next \(y\)-value, \(y_{n+1}\), gives the iterative step:$$ y_{n+1} \approx y_n + h \cdot f(x_n, y_n). $$The collection of line segments created by this iterative procedure forms a polygonal approximation to the true solution curve.

The method begins with an initial condition \((x_0, y_0)\) and proceeds in steps. Let's define a small, constant step size, \(h\). The \(x\)-coordinate of each subsequent point is found by adding this step size: \(x_{n+1} = x_n + h\).

The core of the method is to approximate the derivative \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\) using the gradient of the line segment connecting two consecutive points, \((x_n, y_n)\) and \((x_{n+1}, y_{n+1})\):$$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} \text{ at } (x_n, y_n) \approx \dfrac{y_{n+1} - y_n}{x_{n+1} - x_n} = \dfrac{y_{n+1} - y_n}{h}. $$Since the differential equation gives us the exact value of the derivative, \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = f(x_n, y_n)\), we can set these equal:$$ \dfrac{y_{n+1} - y_n}{h}\approx f(x_n, y_n). $$Rearranging this formula to find the next \(y\)-value, \(y_{n+1}\), gives the iterative step:$$ y_{n+1} \approx y_n + h \cdot f(x_n, y_n). $$The collection of line segments created by this iterative procedure forms a polygonal approximation to the true solution curve.

Method Euler's Method

To approximate the solution to \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = f(x,y)\) with initial condition \((x_0, y_0)\) and a step size \(h\), the coordinates of the next point \((x_{n+1}, y_{n+1})\) are found from the previous point \((x_n, y_n)\) using the iterative formulas:$$\begin{cases}x_{n+1} = x_n + h, \\

y_{n+1} = y_n + h \cdot f(x_n, y_n).\end{cases}$$