Coupled Differential Equations

In the previous chapter, we studied single differential equations describing a single quantity changing over time. However, in the real world, systems often involve multiple variables that interact with one another. For example, the population of predators (like foxes) depends on the population of prey (like rabbits), and vice versa.

These situations are modeled by coupled differential equations. In this chapter, we will learn how to visualize these systems using phase portraits, solve systems of linear equations using matrices, eigenvalues, and eigenvectors, and approximate solutions using Euler's method.

These situations are modeled by coupled differential equations. In this chapter, we will learn how to visualize these systems using phase portraits, solve systems of linear equations using matrices, eigenvalues, and eigenvectors, and approximate solutions using Euler's method.

Definitions and Equilibrium

Definition System of coupled first-order differential equations

A system of coupled first-order differential equations usually takes the form:$$\begin{cases}\dfrac{dx}{dt} = f(x, y) \\

\dfrac{dy}{dt} = g(x, y)\end{cases}$$Here, \(t\) is the independent variable (often time), while \(x\) and \(y\) are the dependent variables (state variables).

We often denote the time derivatives using dot notation: \(\dot{x} = \dfrac{dx}{dt}\) and \(\dot{y} = \dfrac{dy}{dt}\).

We often denote the time derivatives using dot notation: \(\dot{x} = \dfrac{dx}{dt}\) and \(\dot{y} = \dfrac{dy}{dt}\).

Definition Equilibrium Points

An equilibrium point is a state where the system does not change. This occurs when both derivatives are zero simultaneously:$$ \frac{dx}{dt} = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad \frac{dy}{dt} = 0 $$

Example

Consider the system:$$ \frac{dx}{dt} = y \quad \text{and} \quad \frac{dy}{dt} = -x $$To find the equilibrium points, we set both derivatives to zero:$$ y = 0 \quad \text{and} \quad -x = 0 $$The only solution is \((x, y) = (0, 0)\). Thus, the origin is the only equilibrium point.

Phase Portrait

Definition Phase Portrait

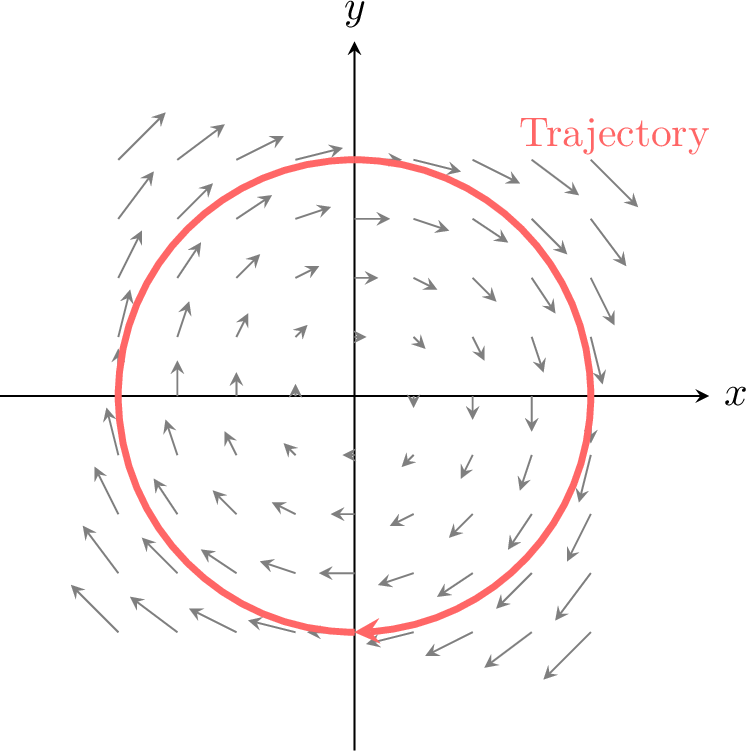

A phase portrait is a graphical representation where:

- The axes represent the state variables \(x\) and \(y\) (not \(t\)).

- At each point \((x, y)\), the vector \(\begin{pmatrix} \dot{x} \\ \dot{y} \end{pmatrix}\) indicates the direction and speed of change.

- Trajectories are curves that follow the flow of these vectors, showing how the state of the system evolves over time starting from a specific initial condition.

Example

Consider the system:$$ \frac{dx}{dt} = y \quad \text{and} \quad \frac{dy}{dt} = -x $$Let's calculate the velocity vector at a few points:

- At \((1, 0)\), vector is \(\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ -1 \end{pmatrix}\) (Straight down).

- At \((0, -1)\), vector is \(\begin{pmatrix} -1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\) (Straight left).

- At \((-1, 0)\), vector is \(\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\) (Straight up).

- At \((0, 1)\), vector is \(\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\) (Straight right).

Coupled Linear Differential Equations

A fundamental type of coupled system is the linear system with constant coefficients.

These systems can be elegantly solved using matrix algebra. By defining a vector \(\mathbf{x} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}\) and a matrix \(\mathbf{A}\), we can condense the system into the compact form \(\dot{\mathbf{x}} = \mathbf{A}\mathbf{x}\).

These systems can be elegantly solved using matrix algebra. By defining a vector \(\mathbf{x} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}\) and a matrix \(\mathbf{A}\), we can condense the system into the compact form \(\dot{\mathbf{x}} = \mathbf{A}\mathbf{x}\).

Definition Coupled Linear Differential Equations

A system of coupled linear differential equations is a set of equations of the form:$$\begin{cases}\dfrac{dx}{dt} = ax + by \\

\dfrac{dy}{dt} = cx + dy\end{cases}$$This can be written in matrix form as:$$ \begin{pmatrix} \dot{x} \\

\dot{y} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\

c & d \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\

y \end{pmatrix} \iff \dot{\mathbf{x}} = \mathbf{A}\mathbf{x} $$where \(\mathbf{A} = \begin{pmatrix} a & b \\ c & d \end{pmatrix}\) is the matrix of coefficients.

To find the solution, we look for an analogue to the scalar solution \(x = x_0 e^{kt}\).

If we propose a trial solution of the form \(\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{v}e^{\lambda t}\), differentiating gives \(\dot{\mathbf{x}} = \lambda \mathbf{v}e^{\lambda t}\). Substituting this into the system yields:$$ \lambda \mathbf{v}e^{\lambda t} = \mathbf{A}(\mathbf{v}e^{\lambda t}) \implies \mathbf{A}\mathbf{v} = \lambda \mathbf{v} $$This equation holds true precisely when \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) is the corresponding eigenvector.

If we propose a trial solution of the form \(\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{v}e^{\lambda t}\), differentiating gives \(\dot{\mathbf{x}} = \lambda \mathbf{v}e^{\lambda t}\). Substituting this into the system yields:$$ \lambda \mathbf{v}e^{\lambda t} = \mathbf{A}(\mathbf{v}e^{\lambda t}) \implies \mathbf{A}\mathbf{v} = \lambda \mathbf{v} $$This equation holds true precisely when \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of \(\mathbf{A}\) and \(\mathbf{v}\) is the corresponding eigenvector.

Proposition General Solution using Eigenvalues

Let \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\) be the distinct real eigenvalues of matrix \(\mathbf{A}\), with corresponding eigenvectors \(\mathbf{v}_1\) and \(\mathbf{v}_2\). The general solution is:$$ \mathbf{x}(t) = A e^{\lambda_1 t} \mathbf{v}_1 + B e^{\lambda_2 t} \mathbf{v}_2 $$where \(A\) and \(B\) are arbitrary constants determined by initial conditions.

Example

Solve the system \(\begin{cases} \dfrac{dx}{dt} = 4x - 2y \\ \dfrac{dy}{dt} = x + y \end{cases}\).

The matrix is \(\mathbf{A} = \begin{pmatrix} 4 & -2 \\ 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix}\).

- Find eigenvalues: $$\begin{aligned} \det(\mathbf{A} - \lambda \mathbf{I}) &= 0\\ (4-\lambda)(1-\lambda) - (-2)(1) &= 0\\ 4 - 5\lambda + \lambda^2 + 2 &= 0\\ \lambda^2 - 5\lambda + 6 &= 0\\ (\lambda - 3)(\lambda - 2) &= 0 \end{aligned}$$ The eigenvalues are \(\lambda_1 = 3\) and \(\lambda_2 = 2\).

- Find eigenvector for \(\lambda_1 = 3\): $$\begin{pmatrix} 4 & -2 \\ 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} = 3\begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} \implies \begin{pmatrix} 1 & -2 \\ 1 & -2 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}$$ \(x - 2y = 0 \implies x = 2y\). Let \(y=1\), then \(x=2\). So \(\mathbf{v}_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\).

- Find eigenvector for \(\lambda_2 = 2\): $$\begin{pmatrix} 4 & -2 \\ 1 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} = 2\begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} \implies \begin{pmatrix} 2 & -2 \\ 1 & -1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}$$ \(x - y = 0 \implies x = y\). Let \(y=1\), then \(x=1\). So \(\mathbf{v}_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\).

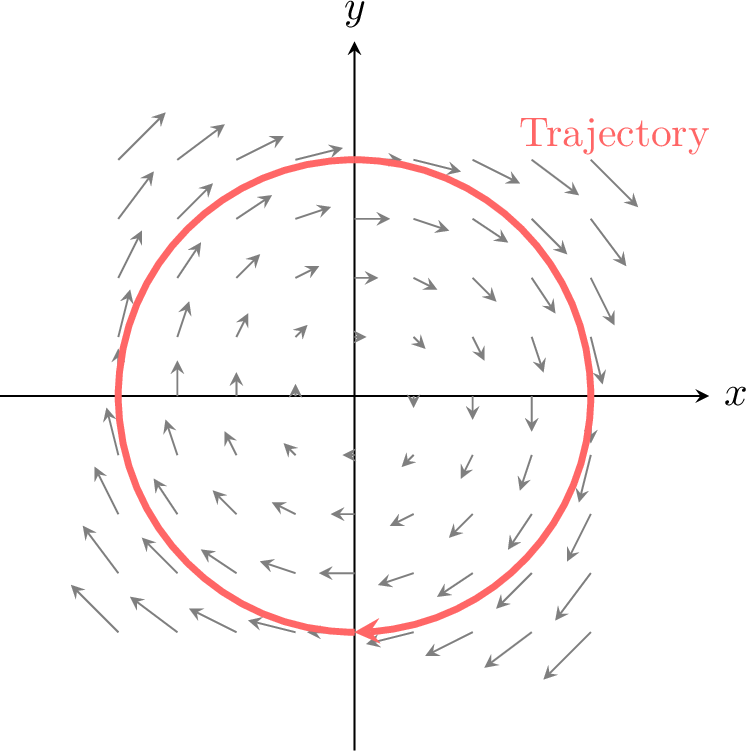

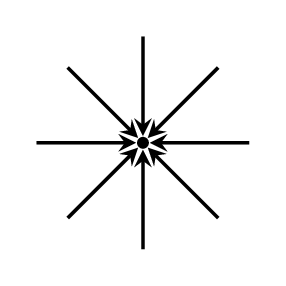

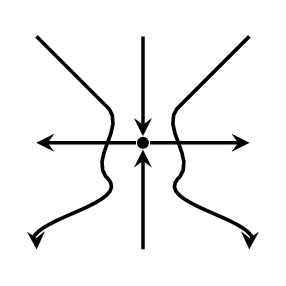

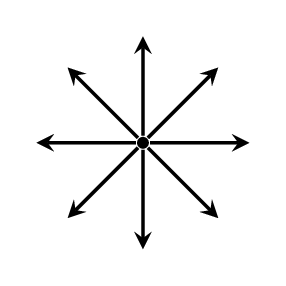

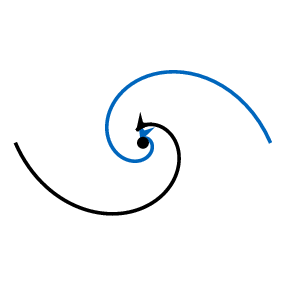

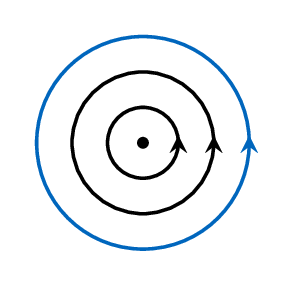

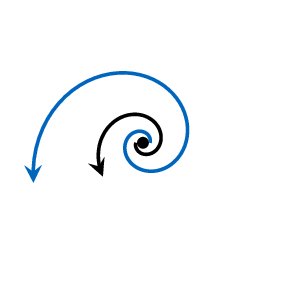

Proposition Classification of Equilibrium Points

We can describe the behaviour of the phase portrait around an equilibrium point (after translating it to the origin) based on the eigenvalues \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2\) of the system's matrix.

| Stable Node (Sink) | Saddle Point | Unstable Node (Source) |

| {\small \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2 < 0\)} | {\small \(\lambda_1 > 0 > \lambda_2\)} | {\small \(\lambda_1, \lambda_2 > 0\)} |

|  |  |

| Stable Spiral | Center | Unstable Spiral |

| {\small Complex, Re\((\lambda) < 0\)} | {\small Pure Imaginary} | {\small Complex, Re\((\lambda) > 0\)} |

|  |  |

Second Order Differential Equations

Second-order differential equations play a crucial role in physics and engineering. Since Newton's Second Law relates force to acceleration (the second derivative of position), these equations naturally describe mechanical vibrations, such as springs, dampers, and pendulums. Similarly, in electronics, they are essential for modeling the behavior of RLC electrical circuits.

Definition Second-Order Linear Homogeneous Differential Equation

A second-order linear homogeneous differential equation with constant coefficients is an equation of the form:$$ a\frac{d^2x}{dt^2} + b\frac{dx}{dt} + cx = 0 $$where \(a, b,\) and \(c\) are constants and \(a \neq 0\).

- Second-order: The highest derivative is the second derivative.

- Linear: The variable \(x\) and its derivatives appear to the first power and are not multiplied together.

- Homogeneous: The equation equals zero (there is no external forcing term).

Method Reduction to a System

Any second-order linear homogeneous differential equation of the form$$ a\frac{d^2x}{dt^2} + b\frac{dx}{dt} + cx = 0 $$can be converted into a system of two first-order equations.

- Introduce a new variable \(y = \dfrac{dx}{dt}\) (velocity).

- Differentiate \(y\): \(\dfrac{dy}{dt} = \dfrac{d^2x}{dt^2}\).

- Rearrange the original equation: \(\dfrac{dy}{dt} = -\frac{b}{a}y - \frac{c}{a}x\).

- Write as a matrix system: $$ \begin{pmatrix} \dfrac{dx}{dt} \\ \dfrac{dy}{dt} \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ -\frac{c}{a} & -\frac{b}{a} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix} $$

Example

Convert the second-order differential equation \(\dfrac{d^2x}{dt^2} + 3\dfrac{dx}{dt} + 2x = 0\) into a system of coupled first-order equations.

Let \(y = \dfrac{dx}{dt}\). Then:$$ \begin{aligned}\dfrac{dy}{dt} &= \frac{d}{dt}\left(\frac{dx}{dt}\right) = \frac{d^2x}{dt^2} \\

\end{aligned} $$From the original equation, we rearrange to isolate the second derivative:$$ \frac{d^2x}{dt^2} = -2x - 3\frac{dx}{dt} $$Substituting \(y\) into this expression:$$ \dfrac{dy}{dt} = -2x - 3y $$The system of coupled equations is:$$\begin{cases}\dfrac{dx}{dt} = y \\

\dfrac{dy}{dt} = -2x - 3y\end{cases}$$

Euler's Method for Coupled Systems

When exact solutions are difficult to find (e.g., non-linear systems), we use Euler's method to approximate the trajectory. For a system \(\dfrac{dx}{dt} = f(x, y)\) and \(\dfrac{dy}{dt} = g(x, y)\) with step size \(h\):

Method Iterative Formulas

Given initial values \((x_n, y_n)\) at time \(t_n\):

- Calculate the slopes: \(m_x = f(x_n, y_n)\) and \(m_y = g(x_n, y_n)\).

- Update the variables: $$ x_{n+1} = x_n + h \cdot m_x $$ $$ y_{n+1} = y_n + h \cdot m_y $$ $$ t_{n+1} = t_n + h $$

Example

Approximate the solution for \(\begin{cases} \dfrac{dx}{dt} = x + y \\ \dfrac{dy}{dt} = x - y \end{cases}\) with initial condition \(x(0)=1, y(0)=0\) and step size \(h=0.1\).

- Step 0: \(t_0=0, x_0=1, y_0=0\).

- Step 1: $$ \dfrac{dx}{dt}\bigg|_{(1,0)} = 1+0 = 1 \implies x_1 = 1 + 0.1(1) = 1.1 $$$$ \dfrac{dy}{dt}\bigg|_{(1,0)} = 1-0 = 1 \implies y_1 = 0 + 0.1(1) = 0.1 $$

- Step 2: $$ \dfrac{dx}{dt}\bigg|_{(1.1,0.1)} = 1.1 + 0.1 = 1.2 \implies x_2 = 1.1 + 0.1(1.2) = 1.22 $$$$ \dfrac{dy}{dt}\bigg|_{(1.1,0.1)} = 1.1 - 0.1 = 1.0 \implies y_2 = 0.1 + 0.1(1.0) = 0.2 $$