Applications of Integration In Geometry

Calculating Geometric Area

In the previous chapter, we defined the definite integral \(\int_a^b f(x)\,dx\) as the signed area between the graph of \(y=f(x)\) and the \(x\)-axis. This means that areas above the x-axis are positive, while areas below are negative.

However, when a problem asks for the geometric area or simply the area of a region, it refers to the physical, positive space the region occupies. In this case, we must ensure that all parts of the region, whether they are above or below the x-axis, contribute a positive value to the total. This section outlines a method for calculating this total geometric area.

However, when a problem asks for the geometric area or simply the area of a region, it refers to the physical, positive space the region occupies. In this case, we must ensure that all parts of the region, whether they are above or below the x-axis, contribute a positive value to the total. This section outlines a method for calculating this total geometric area.

Method Calculating Geometric Area Bounded by a Curve and the x-axis

To find the total geometric area \(\mathcal{A}\) bounded by a curve \(y=f(x)\) and the x-axis from \(x=a\) to \(x=b\):

- Find the \(x\)-intercepts: Determine where the function crosses the \(x\)-axis by solving \(f(x)=0\). Identify any roots \(c_1, c_2, \dots\) that lie within the interval \([a,b]\).

- Split the integral: Divide the main integral into smaller integrals at each intercept found in the previous step.

- Calculate each definite integral: Compute the integral for each sub-interval. Some of these will correspond to positive values (where \(f(x) \ge 0\)) and some to negative values (where \(f(x) \le 0\)).

- Sum the absolute values: The total geometric area is the sum of the absolute values of these integrals. If the integral of a sub-region is negative, take its positive value before adding it to the total.

Example

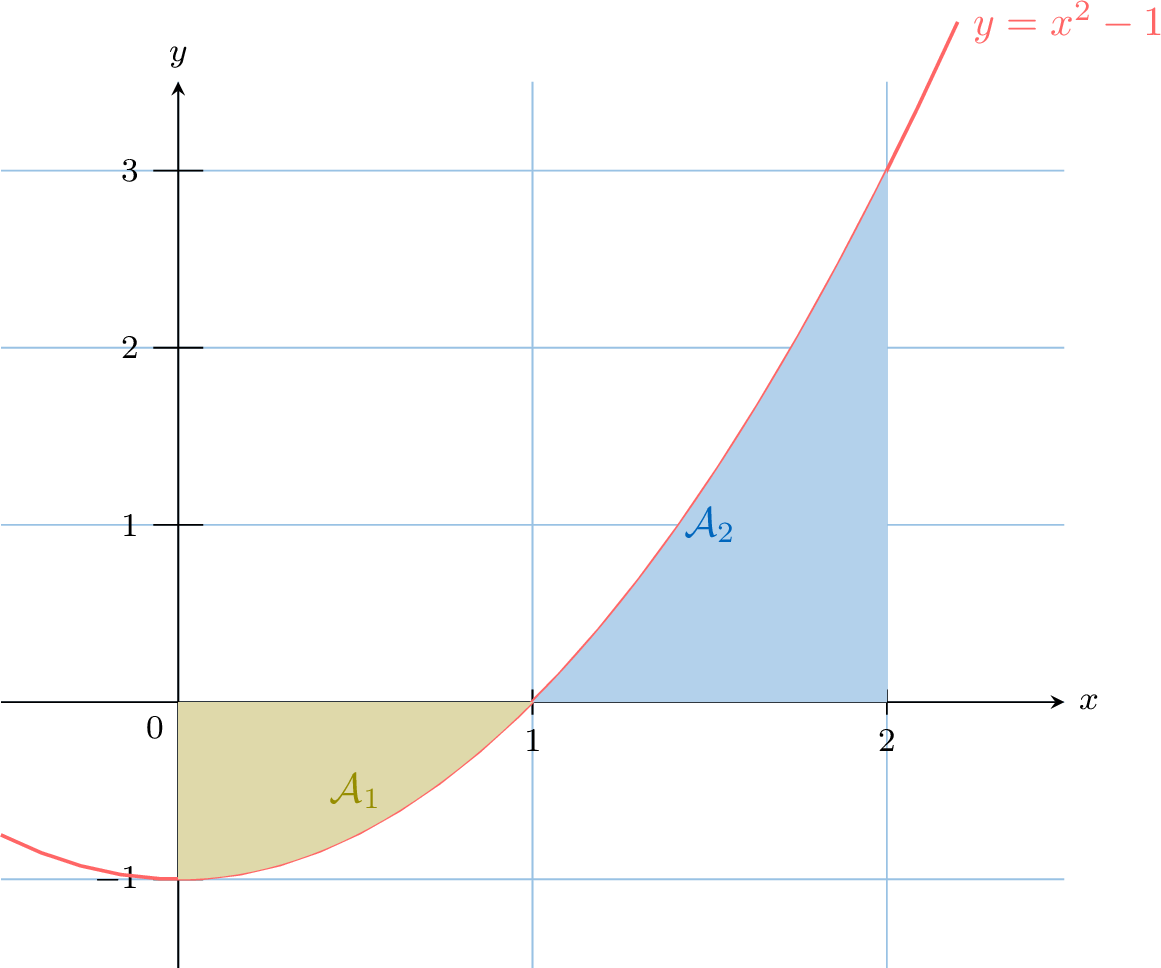

Find the total geometric area between the curve \(y=x^2-1\) and the \(x\)-axis from \(x=0\) to \(x=2\).

- Find intercepts: We solve \(f(x)=x^2-1=0\), which gives roots at \(x=1\) and \(x=-1\). The only root within our interval of integration \([0,2]\) is \(x=1\).

- Split the integral: We must split the total area calculation at \(x=1\).

- From \(x=0\) to \(x=1\), the function is below the \(x\)-axis (Area \(\mathcal{A}_1\)).

- From \(x=1\) to \(x=2\), the function is above the \(x\)-axis (Area \(\mathcal{A}_2\)).

- Calculate each integral: $$ \int_0^1 (x^2-1)\, dx = \left[\frac{x^3}{3}-x\right]_0^1 = \left(\frac{1}{3}-1\right) - 0 = -\frac{2}{3} $$ $$ \int_1^2 (x^2-1)\, dx = \left[\frac{x^3}{3}-x\right]_1^2 = \left(\frac{8}{3}-2\right) - \left(\frac{1}{3}-1\right) = \frac{2}{3} - \left(-\frac{2}{3}\right) = \frac{4}{3} $$

- Sum the absolute values: $$ \text{Total Area} = \left|-\frac{2}{3}\right| + \left|\frac{4}{3}\right| = \frac{2}{3} + \frac{4}{3} = \frac{6}{3} = 2 $$

Definition Geometric Area Formula

The total geometric area \(\mathcal{A}\) between the graph of a function \(f(x)\) and the \(x\)-axis from \(x=a\) to \(x=b\) is given by the integral of the absolute value of the function:$$ \mathcal{A} = \int_a^b |f(x)|\, \mathrm dx $$

Note

The method of splitting the integral and summing the absolute values is equivalent to this formal definition of the total geometric area.

Volumes of Revolution

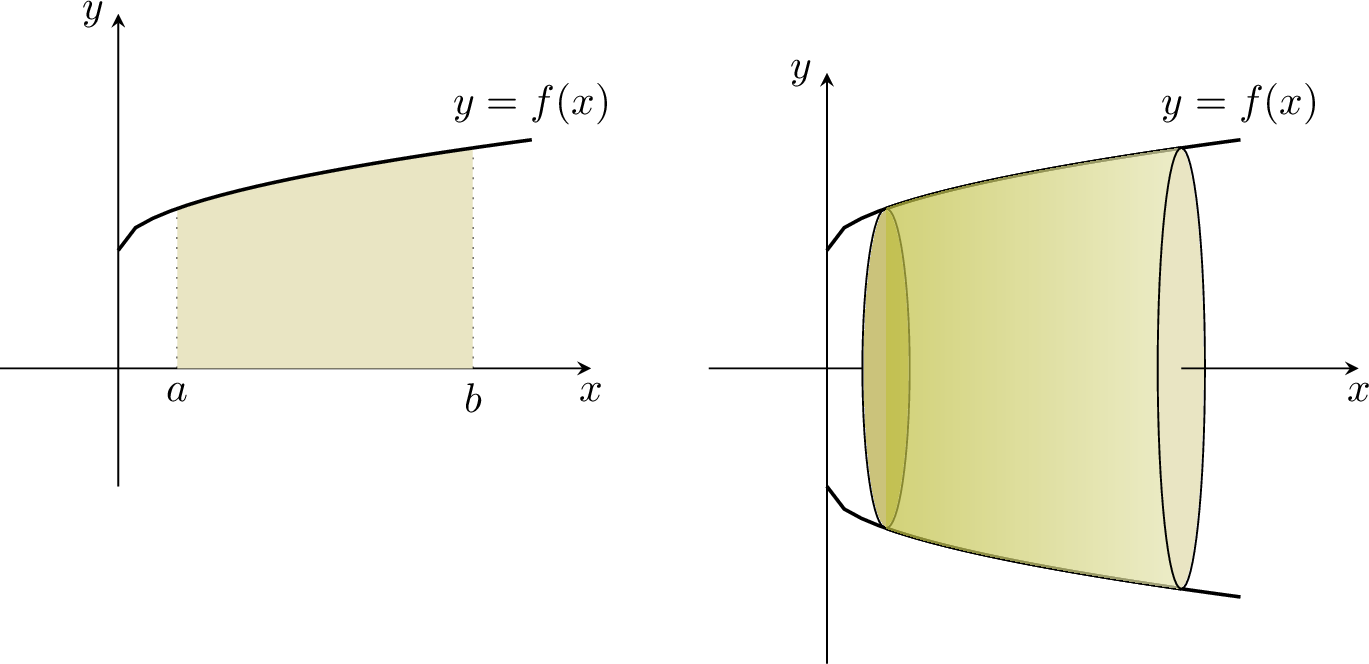

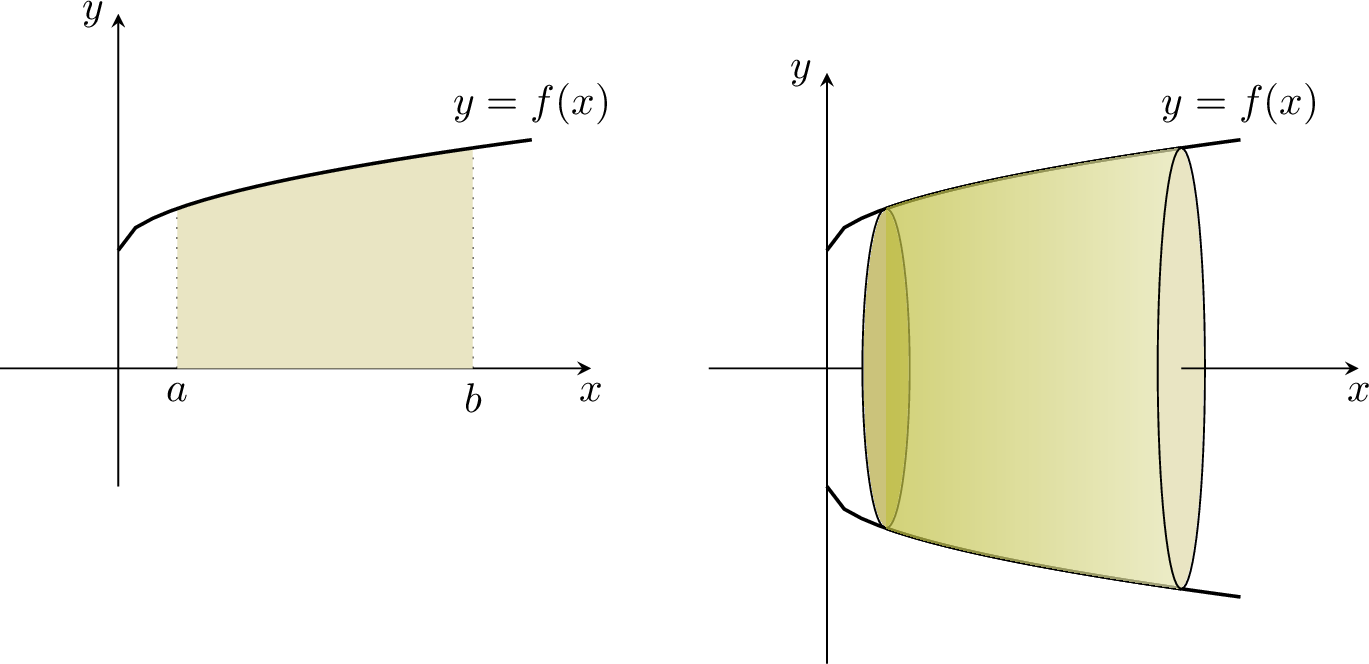

A solid of revolution is a three-dimensional object formed by rotating a two-dimensional shape around an axis. In this section, we will develop a method to find the exact volume of such solids.

Consider the area under the curve \(y=f(x)\) from \(x=a\) to \(x=b\). If we revolve this area \(360^\circ\) (\(2\pi\) radians) around the \(x\)-axis, it sweeps out a solid of revolution.

Consider the area under the curve \(y=f(x)\) from \(x=a\) to \(x=b\). If we revolve this area \(360^\circ\) (\(2\pi\) radians) around the \(x\)-axis, it sweeps out a solid of revolution.

Method The Disk Method

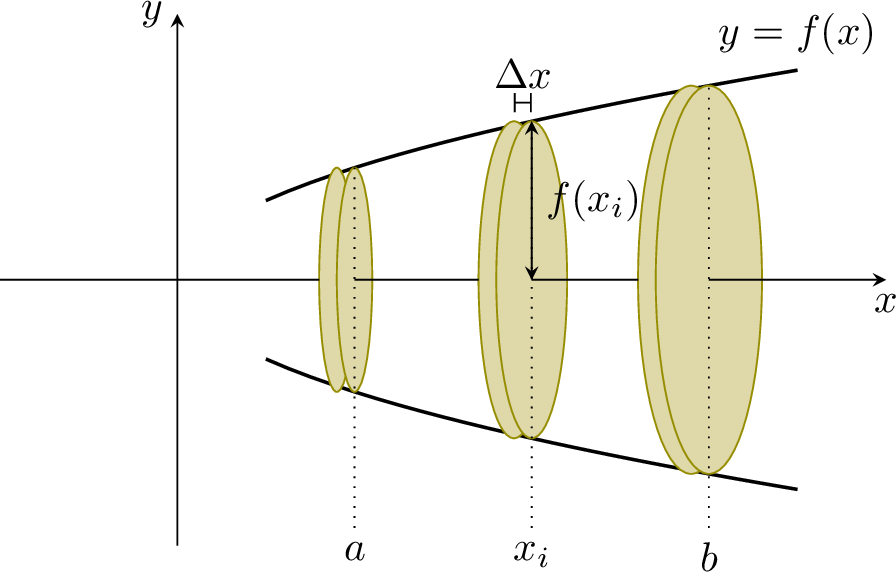

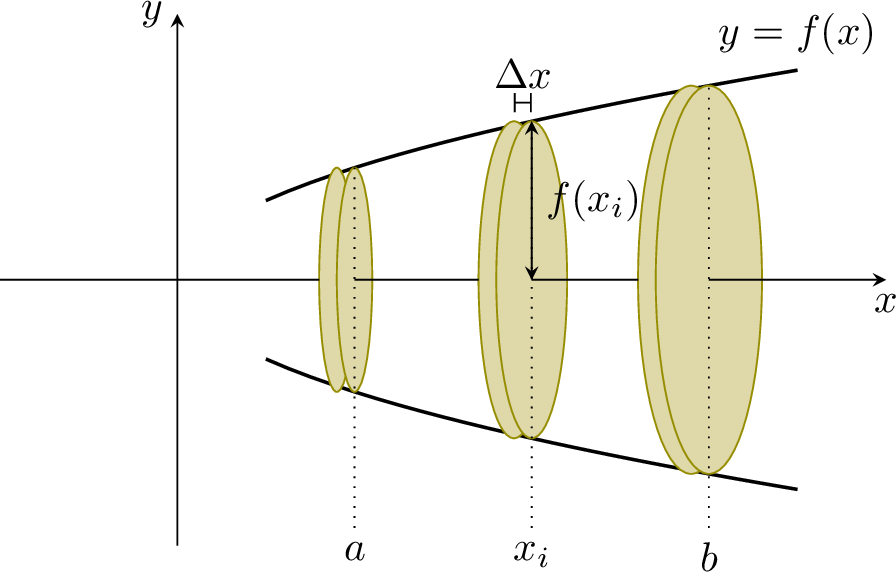

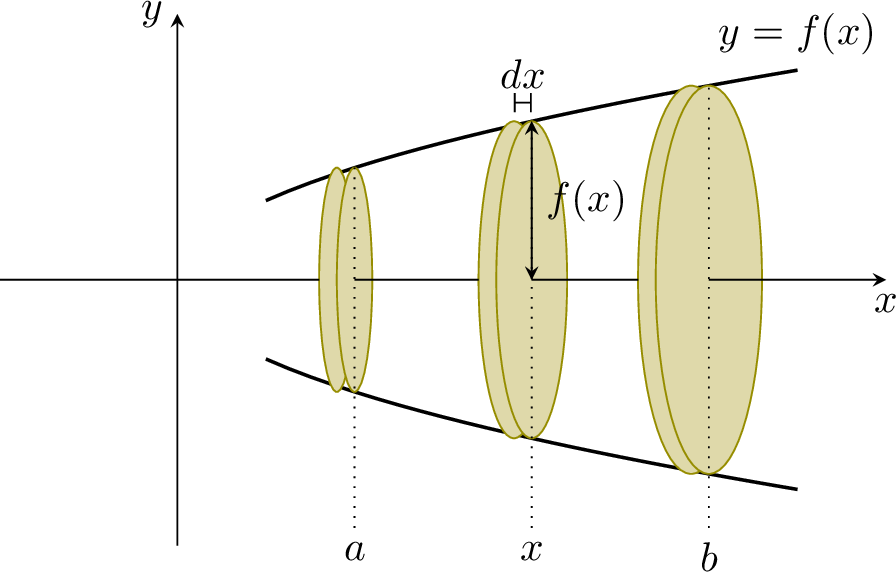

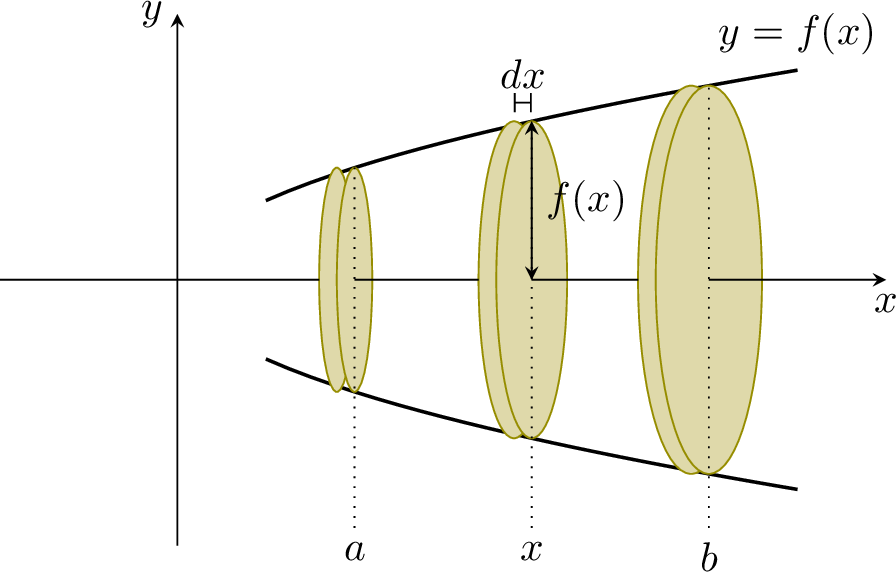

To find the volume of this solid, we use the same strategy as for area: slice the solid into many thin pieces and sum their volumes. In this case, each slice is a thin cylindrical disk. The key insight is that each disk is formed by rotating one of the thin rectangles from a Riemann sum around the \(x\)-axis.

- The radius is the height of the function, \(r = f(x_i)\).

- The height (thickness) of the disk is \(h = \Delta x\).

Proposition Volume of Revolution about the \(x\)-axis

Assuming \(f(x)\geq 0\) on \([a,b]\), the volume \(V\) generated by rotating the region bounded by the curve \(y=f(x)\), the \(x\)-axis, and the lines \(x=a\) and \(x=b\) around the \(x\)-axis is given by:$$ V = \pi \int_a^b [f(x)]^2\, dx $$

Example

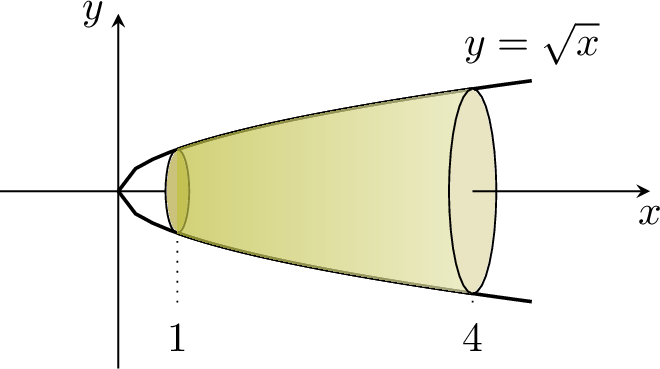

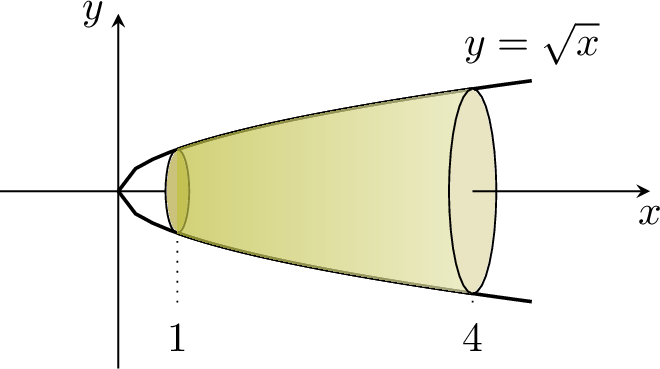

Find the volume of the solid generated by revolving the region under the curve \(y=\sqrt{x}\) from \(x=1\) to \(x=4\) around the \(x\)-axis.

- Identify: The function is \(f(x)=\sqrt{x}\), and the limits are \(a=1\) and \(b=4\).

- Square the function: \([f(x)]^2 = (\sqrt{x})^2 = x\).

- Integrate: We set up and evaluate the integral for the volume: $$\begin{aligned} V &= \pi \int_1^4 x \, dx \\ &= \pi \left[ \frac{x^2}{2} \right]_1^4 \\ &= \pi \left( \frac{4^2}{2} - \frac{1^2}{2} \right) \\ &= \pi \left( \frac{16}{2} - \frac{1}{2} \right) \\ &= \pi \left( 8 - \frac{1}{2} \right)\\ &= \frac{15\pi}{2} \end{aligned}$$

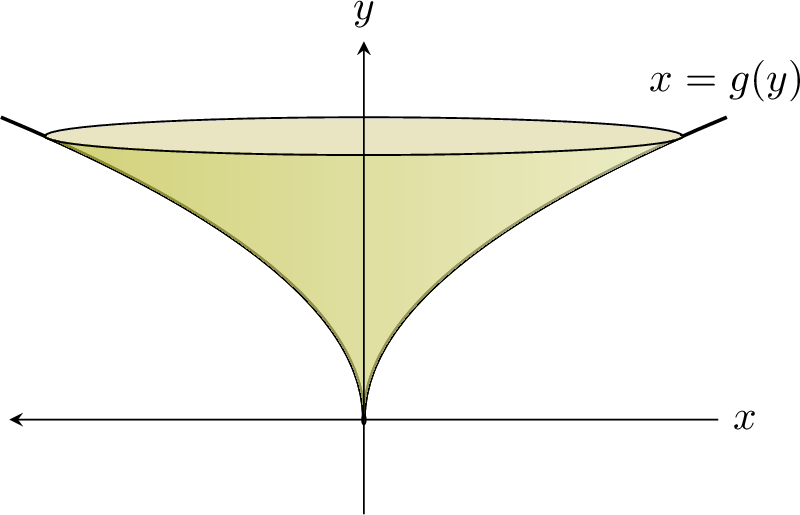

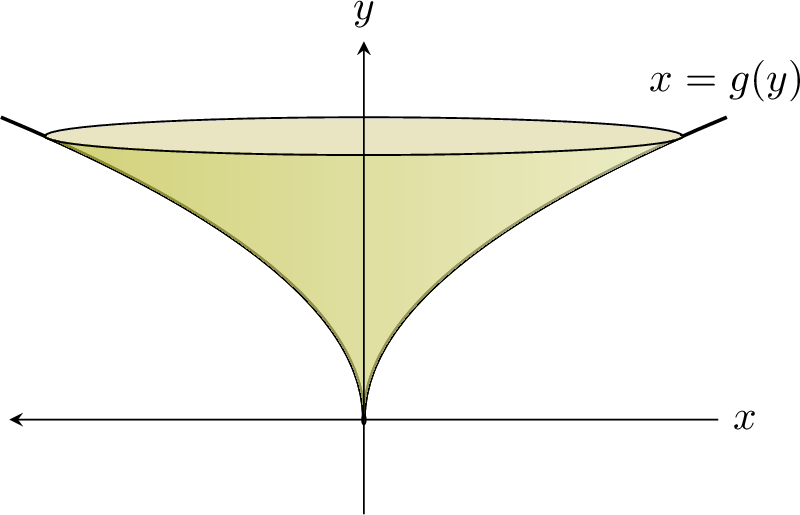

Proposition Volume of Revolution about the y-axis

Assuming \(g(y)\ge 0\) on \([c,d]\), the volume \(V\) generated by rotating the region bounded by the curve \(x=g(y)\), the y-axis, and the lines \(y=c\) and \(y=d\) around the y-axis is given by:$$ V = \pi \int_c^d [g(y)]^2\, dy $$

Note

To use this formula, the function must be expressed in the form \(x=g(y)\), where \(y\) is the independent variable. This may require rearranging the function's equation.

Example

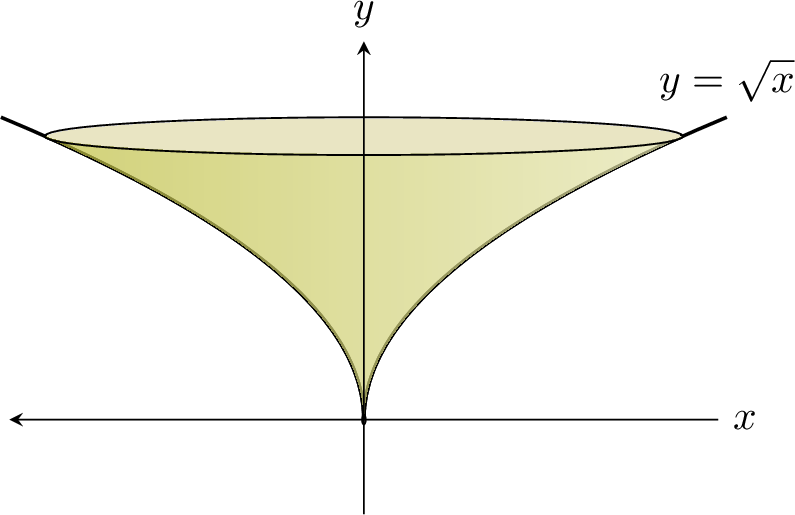

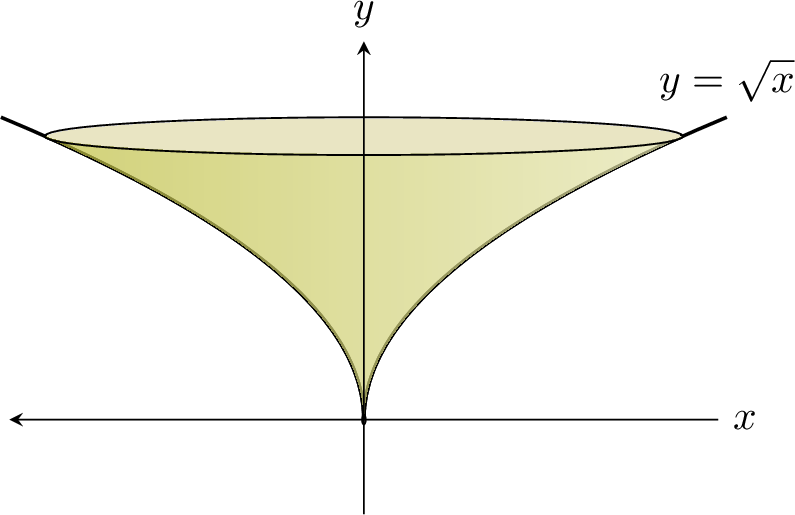

Find the volume of the solid generated by revolving the region bounded by the curve \(y=\sqrt{x}\), the y-axis, and the line \(y=2\) about the y-axis.

- Rearrange the function: The rotation is around the y-axis, so we need to express \(x\) in terms of \(y\): $$ y = \sqrt{x} \implies x = y^2. $$ So, our function is \(g(y)=y^2\).

- Identify limits: The region is bounded by the y-axis (which corresponds to \(x=0\) and starts at \(y=0\), where the curve meets the axis) and the line \(y=2\). So, our limits are \(c=0\) and \(d=2\).

- Integrate: We set up and evaluate the integral for the volume: $$\begin{aligned} V &= \pi \int_0^2 [g(y)]^2\, dy \\ &= \pi \int_0^2 (y^2)^2\, dy \\ &= \pi \int_0^2 y^4\, dy \\ &= \pi \left[ \frac{y^5}{5} \right]_0^2 \\ &= \pi \left( \frac{2^5}{5} - \frac{0^5}{5} \right)\\ &= \frac{32\pi}{5} \end{aligned}$$