Scalar Product

The scalar product, also known as the dot product, is a fundamental operation in vector algebra. It is used in various fields such as physics (for example, when computing work or projections) and in mathematics (for finding angles between vectors and testing orthogonality).

Definition

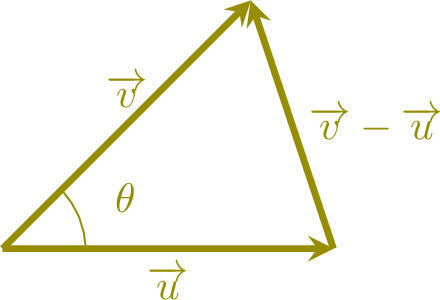

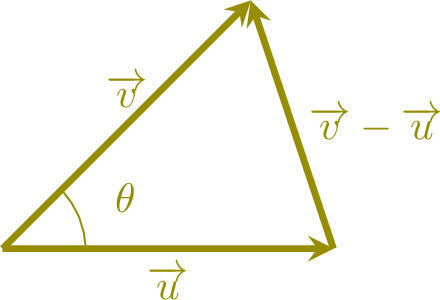

The concept of the scalar product provides a way to multiply two vectors to obtain a scalar (a real number). This operation can be viewed from two fundamental perspectives: a geometric one, involving the angle between the vectors, and an analytical one, using their coordinates. A key result in vector algebra, derived from the Law of Cosines, is that these two perspectives are entirely consistent.

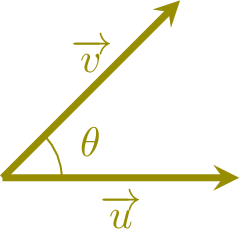

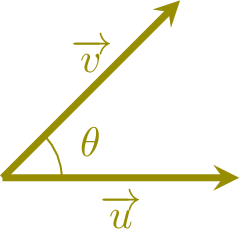

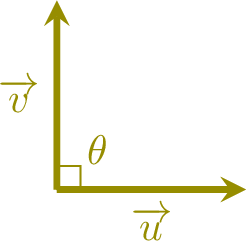

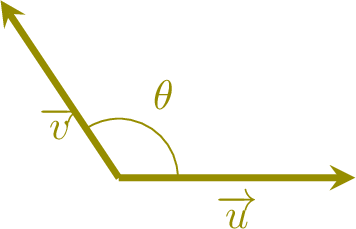

Let's explore this by considering two vectors, \(\Vect{u}=\begin{pmatrix} x \\y\\ \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\Vect{v}=\begin{pmatrix} x' \\y'\\ \end{pmatrix}\), with an angle \(\theta\) between them.

Let's explore this by considering two vectors, \(\Vect{u}=\begin{pmatrix} x \\y\\ \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\Vect{v}=\begin{pmatrix} x' \\y'\\ \end{pmatrix}\), with an angle \(\theta\) between them.

- \(\|\Vect{u}\|^2=x^2 +y^2\)

- \(\|\Vect{v}\|^2=x'^2 +y'^2\)

- \(\|\Vect{v}-\Vect{u}\|^2=\left(x'-x\right)^2+\left(y'-y\right)^2\) since \(\Vect{v}-\Vect{u}=\begin{pmatrix} x'-x \\y'-y\\ \end{pmatrix}\).

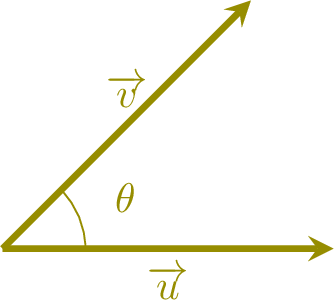

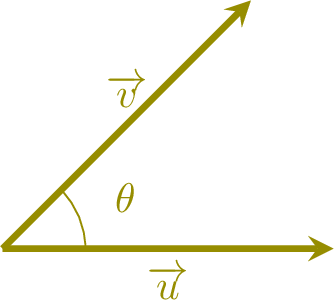

Definition Geometric Scalar Product

The scalar product of two vectors \(\Vect{u}\) and \(\Vect{v}\) is defined as:$$\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = \|\Vect{u}\| \|\Vect{v}\| \cos \theta$$where \(\theta\) is the angle between the vectors.

\(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v}\) is read as ``\(\Vect{u}\) dot \(\Vect{v}\)''.

The scalar product is a real number (a scalar), not a vector. It is: \(\quad\)

\(\quad\) \(\quad\)

\(\quad\)

The scalar product is a real number (a scalar), not a vector. It is:

- positive if \(0< \theta < \frac{\pi}{2}\) (acute angle);

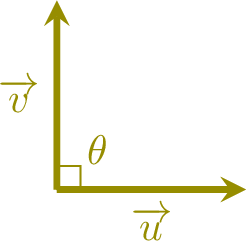

- zero if \(\theta = \frac{\pi}{2}\) (orthogonal vectors), or if at least one of the vectors is the zero vector;

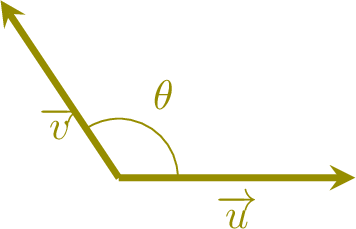

- negative if \(\frac{\pi}{2}<\theta \leq \pi\) (obtuse angle).

\(\quad\)

\(\quad\) \(\quad\)

\(\quad\)

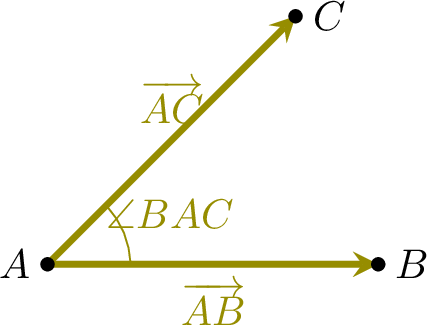

Definition Scalar Product with Point Notation

The scalar product of \(\Vect{AB}\) and \(\Vect{AC}\) is given by:$$\Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AC} = AB \times AC \times \cos(\Angle{BAC}),$$where \(AB\) and \(AC\) denote the lengths of the segments \([AB]\) and \([AC]\).

Example

Given \(AB = 2\), \(AC = 5\), and \(\Angle{BAC} = \frac{\pi}{4}\), calculate \(\Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AC}\).

$$\begin{aligned}\Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AC} &= AB \times AC \times \cos(\Angle{BAC}) \\

&= 2 \times 5 \times \cos\left( \frac{\pi}{4} \right)\\

&= 10 \times \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\\

&= 5 \sqrt{2}\\

\end{aligned}$$

Definition Analytic Scalar Product

For vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with coordinates \(\Vect{u} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\Vect{v} = \begin{pmatrix} x' \\ y' \end{pmatrix}\), the scalar product is defined by:$$\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = xx' + yy'.$$For vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) with coordinates \(\Vect{u} =\begin{pmatrix} x \\ y\\ z \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\Vect{v} = \begin{pmatrix} x' \\ y'\\ z' \end{pmatrix}\), this generalises to:$$\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = xx' + yy' +zz'.$$

Properties

Proposition Square of a vector

$$\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{u} = \|\Vect{u}\|^2$$

Let \(\Vect{u} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}\). Using the analytical definition:$$\begin{aligned}[t] \Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{u} &= x \cdot x + y \cdot y \\

& =x^2 + y^2\\

&= ( \sqrt{x^2+y^2} )^2\\

&= \|\Vect{u}\|^2\end{aligned}$$

Proposition Symmetry

The scalar product is commutative:$$\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = \Vect{v} \cdot \Vect{u}.$$

Let \(\Vect{u} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\Vect{v} = \begin{pmatrix} x' \\ y' \end{pmatrix}\). Using the analytical definition and commutativity of real multiplication:$$\begin{aligned}[t] \Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} &= xx' + yy' \\

& = x'x + y'y\\

&=\Vect{v} \cdot \Vect{u}.\\

\end{aligned}$$

Proposition Bilinearity

The scalar product is linear with respect to each of its vector arguments.

- \(\Vect{u} \cdot (\Vect{v} + \Vect{w}) = \Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} + \Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{w}\) (distributivity in the second argument);

- \((\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}) \cdot \Vect{w} = \Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{w} + \Vect{v} \cdot \Vect{w}\) (distributivity in the first argument);

- \(\Vect{u} \cdot (k\Vect{v}) = k(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v})\) and \((k\Vect{u})\cdot\Vect{v} = k(\Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{v})\), where \(k\) is a real number.

Proposition Notable Identities

- \(\|\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}\|^2 = \|\Vect{u}\|^2 + 2\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} + \|\Vect{v}\|^2\).

- \(\|\Vect{u} - \Vect{v}\|^2 = \|\Vect{u}\|^2 - 2\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} + \|\Vect{v}\|^2\).

- \((\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}) \cdot (\Vect{u} - \Vect{v}) = \|\Vect{u}\|^2 - \|\Vect{v}\|^2\).

- $$\begin{aligned}[t]\|\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}\|^2 &= (\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}) \cdot (\Vect{u} + \Vect{v})\\ &= \Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{u} + \Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{v} + \Vect{v}\cdot\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}\cdot\Vect{v} && \text{(distributivity)} \\ &= \|\Vect{u}\|^2 + 2(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v}) + \|\Vect{v}\|^2 && \text{(symmetry and \(\Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{u}=\|\Vect{u}\|^2\))}\end{aligned}$$

- $$\begin{aligned}\|\Vect{u} - \Vect{v}\|^2 &= (\Vect{u} - \Vect{v}) \cdot (\Vect{u} - \Vect{v})\\ &= \Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{u} - \Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{v} - \Vect{v}\cdot\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}\cdot\Vect{v} \\ &= \|\Vect{u}\|^2 - 2(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v}) + \|\Vect{v}\|^2\end{aligned}$$

- $$\begin{aligned}(\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}) \cdot (\Vect{u} - \Vect{v}) &= \Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{u} - \Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{v} + \Vect{v}\cdot\Vect{u} - \Vect{v}\cdot\Vect{v} \\ &= \|\Vect{u}\|^2 - \Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{v} + \Vect{u}\cdot\Vect{v} - \|\Vect{v}\|^2 && \text{(symmetry)} \\ &= \|\Vect{u}\|^2 - \|\Vect{v}\|^2\end{aligned}$$

Proposition Polarization Identity

$$\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v}=\frac{1}{2}\left( \|\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}\|^2 - \|\Vect{u}\|^2 - \|\Vect{v}\|^2 \right).$$

This identity is derived directly from the notable identities. Starting from the expansion of \(\|\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}\|^2\):$$ \|\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}\|^2 = \|\Vect{u}\|^2 + 2(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v}) + \|\Vect{v}\|^2.$$We can rearrange the equation to solve for \(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v}\):$$ 2(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v}) = \|\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}\|^2 - \|\Vect{u}\|^2 - \|\Vect{v}\|^2.$$Dividing by 2 gives the identity:$$ \Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = \frac{1}{2} \left( \|\Vect{u} + \Vect{v}\|^2 - \|\Vect{u}\|^2 - \|\Vect{v}\|^2 \right). $$Equivalently, using \(\|\Vect{u} - \Vect{v}\|^2\), one can also show that$$ \Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = \frac{1}{2} \left( \|\Vect{u}\|^2 + \|\Vect{v}\|^2 - \|\Vect{u} - \Vect{v}\|^2 \right). $$

Geometrical Interpretations

Proposition Collinearity Condition

Let \(\Vect{u}\) and \(\Vect{v}\) be two non-zero vectors.

- If \(\Vect{u}\) and \(\Vect{v}\) are collinear and point in the same direction, then \(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = \|\Vect{u}\|\|\Vect{v}\|\).

- If \(\Vect{u}\) and \(\Vect{v}\) are collinear and point in opposite directions, then \(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = -\|\Vect{u}\|\|\Vect{v}\|\).

This follows directly from the geometric definition \(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = \|\Vect{u}\|\|\Vect{v}\|\cos\theta\).

- If the vectors are collinear and have the same direction, the angle \(\theta\) between them is \(0\). Since \(\cos(0) = 1\), the result is \(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = \|\Vect{u}\|\|\Vect{v}\|\).

- If they are collinear and have opposite directions, the angle \(\theta\) is \(\pi\). Since \(\cos(\pi) = -1\), the result is \(\Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = -\|\Vect{u}\|\|\Vect{v}\|\).

Definition Orthogonal Vectors

Two vectors \(\Vect{u}\) and \(\Vect{v}\) are said to be orthogonal if their scalar product is zero:$$\Vect{u} \perp \Vect{v} \iff \Vect{u} \cdot \Vect{v} = 0.$$

Proposition Perpendicular Lines

Two lines \((AB)\) and \((CD)\) are perpendicular if and only if the scalar product of their direction vectors is zero:$$(AB) \perp (CD) \iff \Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{CD} = 0.$$

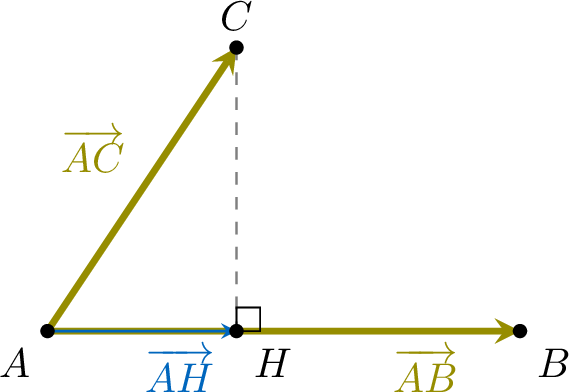

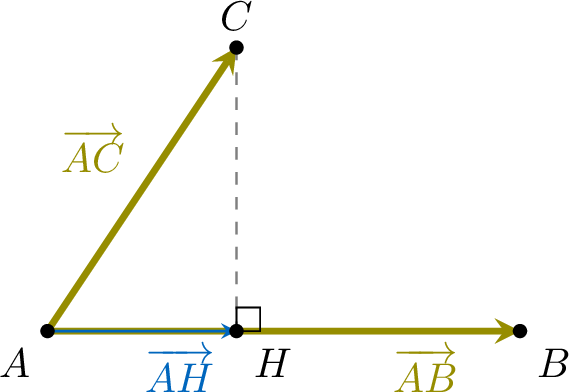

Proposition Orthogonal Projection

Let \(A\), \(B\) and \(C\) be three points. Let \(H\) be the orthogonal projection of point \(C\) onto the line \(\Line{AB}\). Then:$$\Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AC} = \Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AH}.$$

- If \(\Vect{AB}\) and \(\Vect{AH}\) have the same direction, \(\Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AC} = AB \times AH\).

- If \(\Vect{AB}\) and \(\Vect{AH}\) have opposite directions, \(\Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AC} = -AB \times AH\).

Using Chasles's relation, we can write \(\Vect{AC} = \Vect{AH} + \Vect{HC}\):$$\begin{aligned}\Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AC} &= \Vect{AB} \cdot (\Vect{AH} + \Vect{HC}) \\

&= \Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AH} + \Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{HC}.\end{aligned}$$Since \(H\) is the orthogonal projection of \(C\) on \((AB)\), the vectors \(\Vect{AB}\) and \(\Vect{HC}\) are orthogonal. Therefore, their scalar product is zero: \(\Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{HC} = 0\). This leaves us with$$\Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AC} = \Vect{AB} \cdot \Vect{AH}.$$The second part of the proposition follows from the collinearity condition applied to \(\Vect{AB}\) and \(\Vect{AH}\).

Midpoint Theorem and Applications

Proposition Midpoint Theorem

Given two points \(A\) and \(B\) and their midpoint \(I\) (i.e.\ \(I\) is the midpoint of \(\Segment{AB}\)), for any point \(M\) in the plane, we have:$$\Vect{MA} \cdot \Vect{MB}=MI^2-\frac{1}{4} AB^2.$$

Using Chasles's relation, we introduce the midpoint \(I\):$$\begin{aligned}\Vect{MA} \cdot \Vect{MB} &= (\Vect{MI}+\Vect{IA}) \cdot (\Vect{MI}+\Vect{IB})\\

&= (\Vect{MI}+\Vect{IA}) \cdot (\Vect{MI}-\Vect{IA}) && \text{(since \(I\) is the midpoint, \(\Vect{IB}=-\Vect{IA}\))}\\

&= MI^2-IA^2 && \text{(difference of squares identity)}\\

&= MI^2-\left(\frac{1}{2}AB\right)^2 \\

&= MI^2-\frac{1}{4} AB^2 && \text{(since \(IA = \frac{1}{2}AB\))}\end{aligned}$$

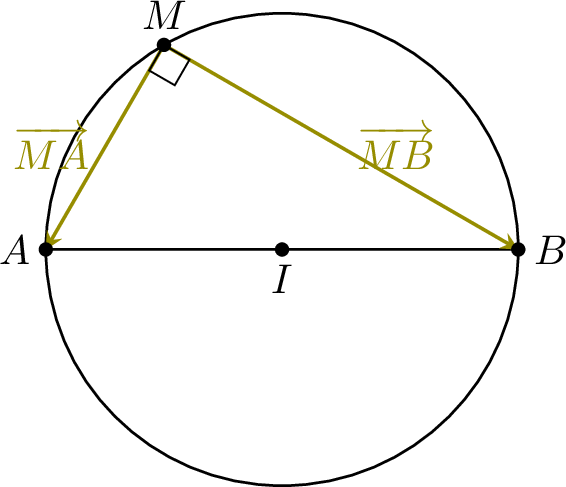

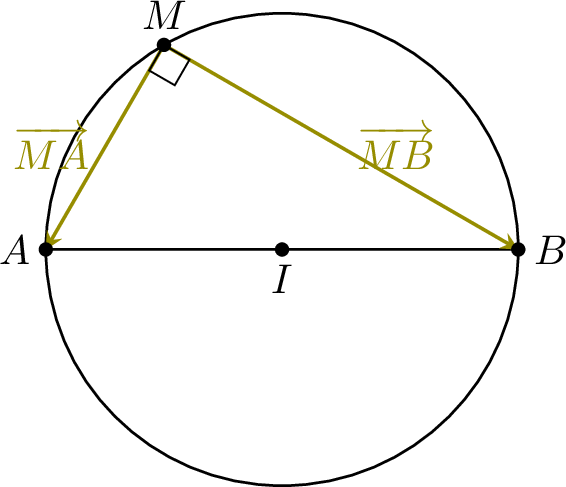

Proposition Circle defined by Orthogonality

The set of all points \(M\) in the plane such that \(\Vect{MA} \cdot \Vect{MB} = 0\) is the circle with diameter \(\Segment{AB}\).

We apply the Midpoint Theorem, which states \(\Vect{MA} \cdot \Vect{MB} = MI^2 - \frac{1}{4}AB^2\). The condition for orthogonality is \(\Vect{MA} \cdot \Vect{MB} = 0\). By substituting, we get:$$\begin{aligned}MI^2 - \frac{1}{4}AB^2 &= 0 \\

MI^2 &= \frac{1}{4}AB^2 \\

MI &= \sqrt{\frac{1}{4}AB^2} \\

MI &= \frac{1}{2}AB.\end{aligned}$$This result means the distance from any point \(M\) to the midpoint \(I\) is constant and equal to half the length of the segment \(\Segment{AB}\). This is the definition of the circle with center \(I\) and diameter \(\Segment{AB}\).