Functions

Fundamental Concepts of Functions

What is a Function?

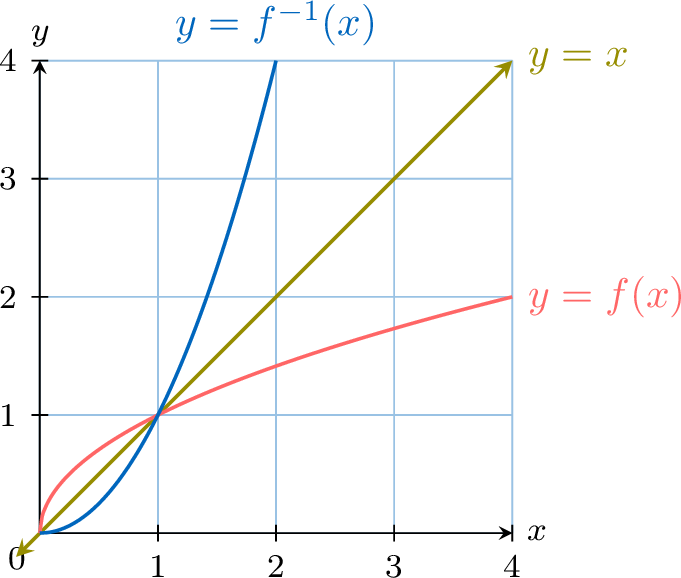

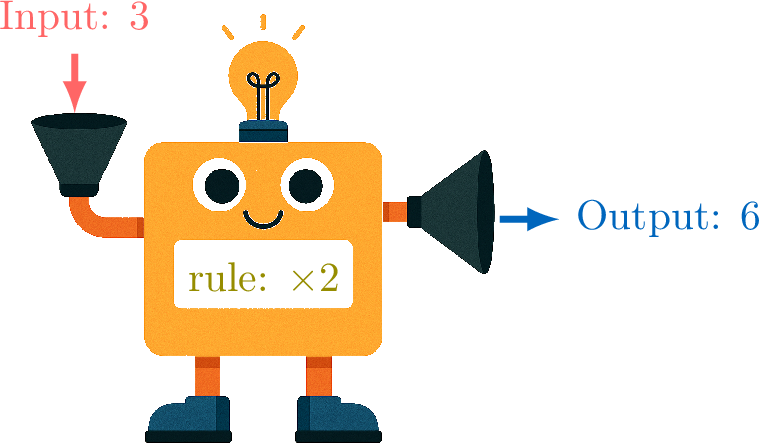

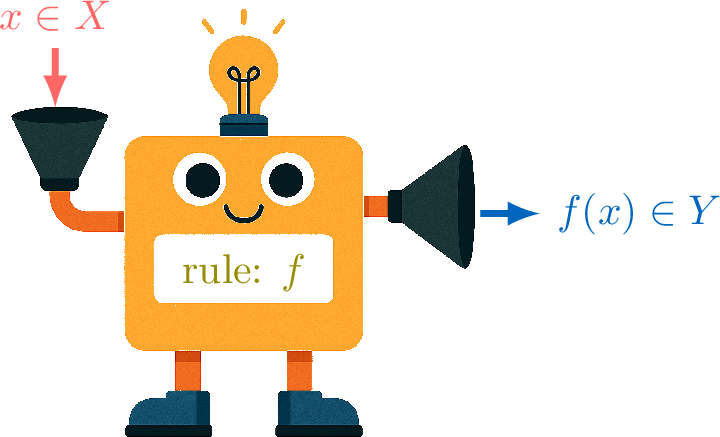

A function is like a machine that follows a specific rule. For every number you put in, you get exactly one number out.

Let's imagine a machine whose rule is "multiply by 2".

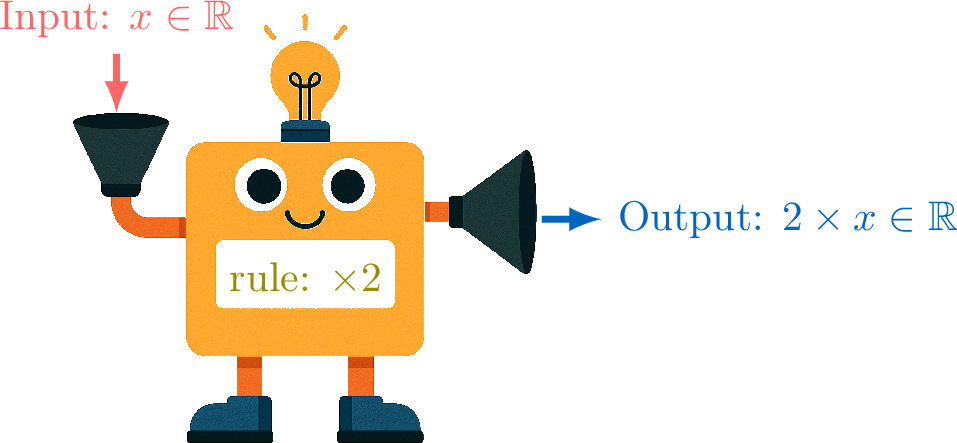

To represent this machine, we write \(\textcolor{olive}{f}(\textcolor{colordef}{\text{input}}) = \textcolor{colorprop}{\text{output}}\). The parentheses \((\) \()\) indicate the action of the function \(\textcolor{olive}{f}\) on the input.

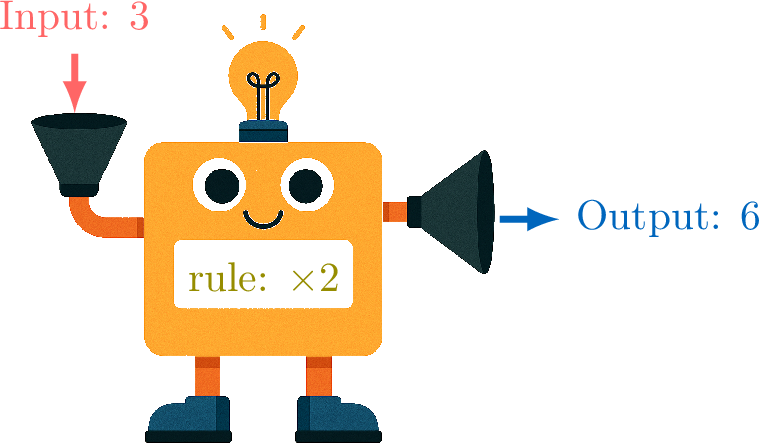

We use function notation to name functions and their variables, replacing "\(\textcolor{colordef}{\text{input}}\)" by "\(\textcolor{colordef}{x}\)" and "\(\textcolor{colorprop}{\text{output}}\)" by "\(\textcolor{colorprop}{f(x)}\)".

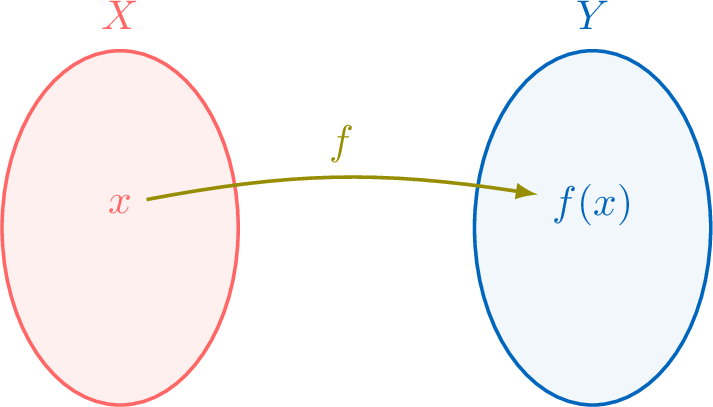

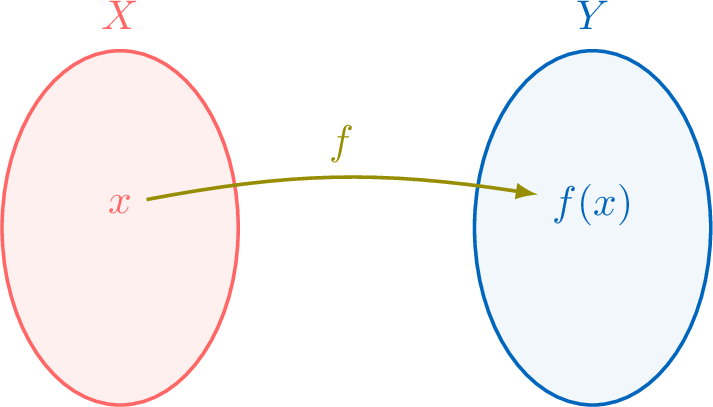

A function maps every element from a set of inputs, the domain \(X\), to an element in a set of possible outputs, the codomain \(Y\). This is written as \(f: X \to Y\). The specific rule that maps an individual element \(x\) from the domain to an element \(f(x)\) in the codomain is written as \(x \mapsto f(x)\).

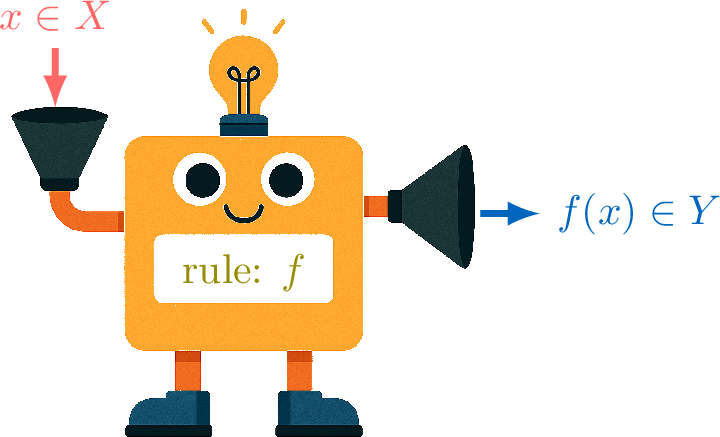

In general we write $$\Function{\textcolor{olive}{f}}{\textcolor{colordef}{X}}{\textcolor{colorprop}{Y}}{\textcolor{colordef}{x}}{\textcolor{colorprop}{f(x)}}$$For example, if the rule is "twice the input" and we are mapping real numbers to real numbers, \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\):

Let's imagine a machine whose rule is "multiply by 2".

| Input | 3 | 5 | 8 | 10 |

| Output | 6 | 10 | 16 | 20 |

To represent this machine, we write \(\textcolor{olive}{f}(\textcolor{colordef}{\text{input}}) = \textcolor{colorprop}{\text{output}}\). The parentheses \((\) \()\) indicate the action of the function \(\textcolor{olive}{f}\) on the input.

We use function notation to name functions and their variables, replacing "\(\textcolor{colordef}{\text{input}}\)" by "\(\textcolor{colordef}{x}\)" and "\(\textcolor{colorprop}{\text{output}}\)" by "\(\textcolor{colorprop}{f(x)}\)".

A function maps every element from a set of inputs, the domain \(X\), to an element in a set of possible outputs, the codomain \(Y\). This is written as \(f: X \to Y\). The specific rule that maps an individual element \(x\) from the domain to an element \(f(x)\) in the codomain is written as \(x \mapsto f(x)\).

In general we write $$\Function{\textcolor{olive}{f}}{\textcolor{colordef}{X}}{\textcolor{colorprop}{Y}}{\textcolor{colordef}{x}}{\textcolor{colorprop}{f(x)}}$$For example, if the rule is "twice the input" and we are mapping real numbers to real numbers, \(f: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}\):

Definition Function

A function \(f: X \to Y\) is a rule that assigns to each element \(x\) in a set \(X\) exactly one element \(f(x)\) in a set \(Y\).

- The set \(X\) of all possible inputs is called the domain of \(f\).

- The set \(Y\) is called the codomain of \(f\).

- \(f\) is the name of the function.

- \(x\) is the input variable, an element from the domain.

- \(f(x)\) is the output value in the codomain when the input is \(x\). It is read as "\(f\) of \(x\)".

- \(f(x)\) is the image of \(x\) under \(f\).

- \(x\) is a preimage of \(y=f(x)\).

Example

Let the function \(\Function{f}{\mathbb{R}}{\mathbb{R}}{x}{2x-1}\). Find the image of \(5\) under \(f\).

To find \(f(5)\), we substitute the input value \(x=5\) into the function's rule:$$\begin{aligned}[t]f(5) &= 2(5) - 1 \\

&= 10 - 1 \\

&= \boldsymbol{9}\end{aligned}$$

Method Finding Inputs from Outputs Algebraically

To find the preimage(s) of a value \(y\) for a function \(f(x)\):

- Set the function's formula equal to the output value: \(\boldsymbol{f(x) = y}\).

- Solve the resulting equation for \(x\).

Example

Let \(f(x) = 3x + 12\). Find \(x\) such that \(f(x)=0\).

We need to find the value of \(x\) such that \(f(x)=0\). We set up the equation and solve:$$\begin{aligned} f(x) &= 0 \\

3x + 12 &= 0 \\

3x &= -12 && \color{gray}\text{(subtract 12 from both sides)} \\

x &= \frac{-12}{3} &&\color{gray}\text{(divide both sides by 3)} \\

x &= -4\end{aligned}$$The preimage of \(0\) is \(\boldsymbol{x = -4}\).

Check: \(f(-4) = 3(-4) + 12 = -12 + 12 = 0\). The answer is correct.

Check: \(f(-4) = 3(-4) + 12 = -12 + 12 = 0\). The answer is correct.

Natural Domain and Range

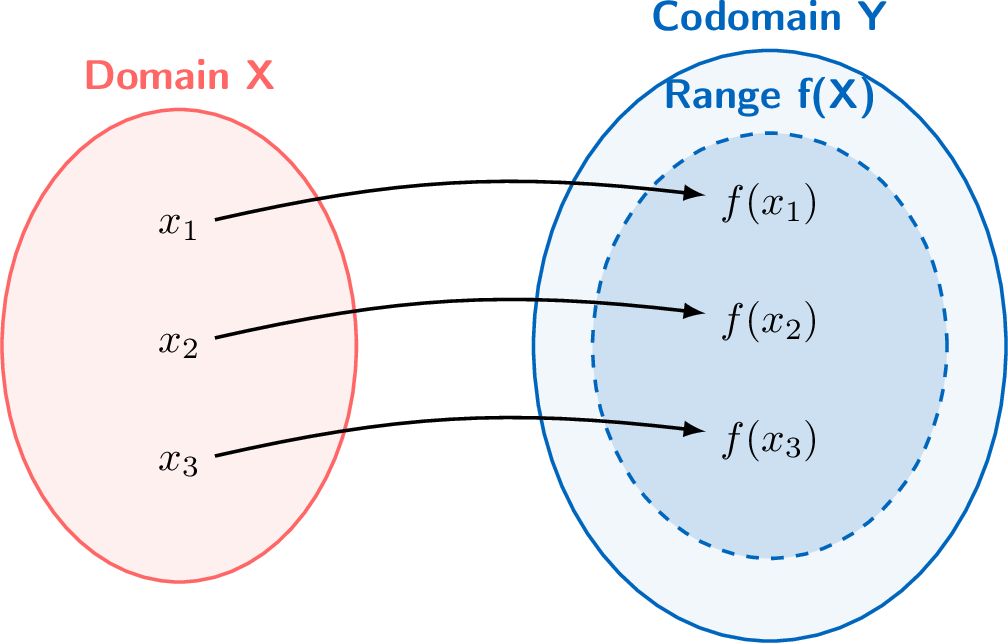

Definition Range

The range of a function \(f:X\to Y\) is the set of all actual output values produced by the function. It is the set of all images of the elements in the domain.$$ \text{Range} = f(X)=\{f(x):x\in X\} $$The range is a subset of the codomain (\(f(X) \subseteq Y\)). While the codomain is the set of potential outputs, the range is the set of actual outputs.

Example

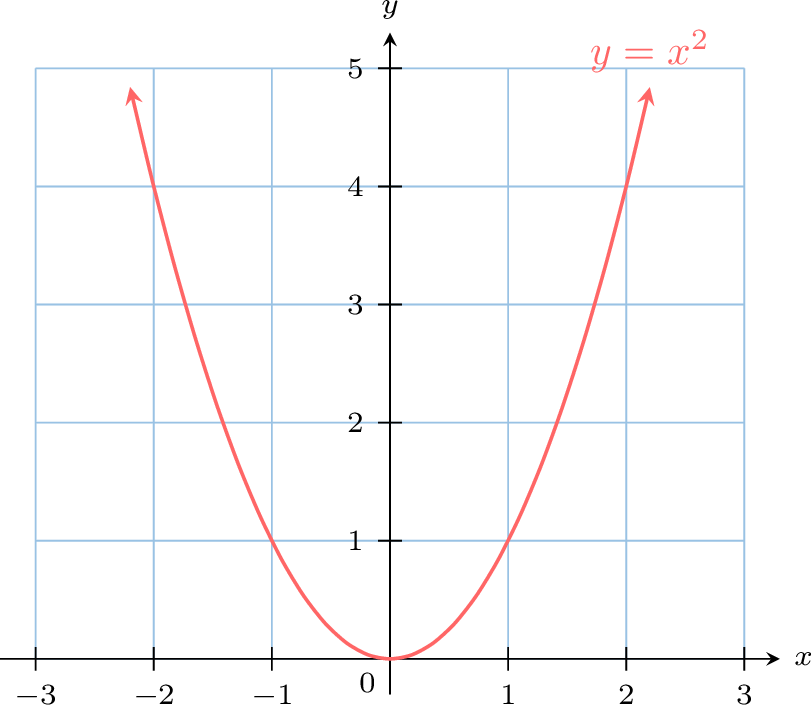

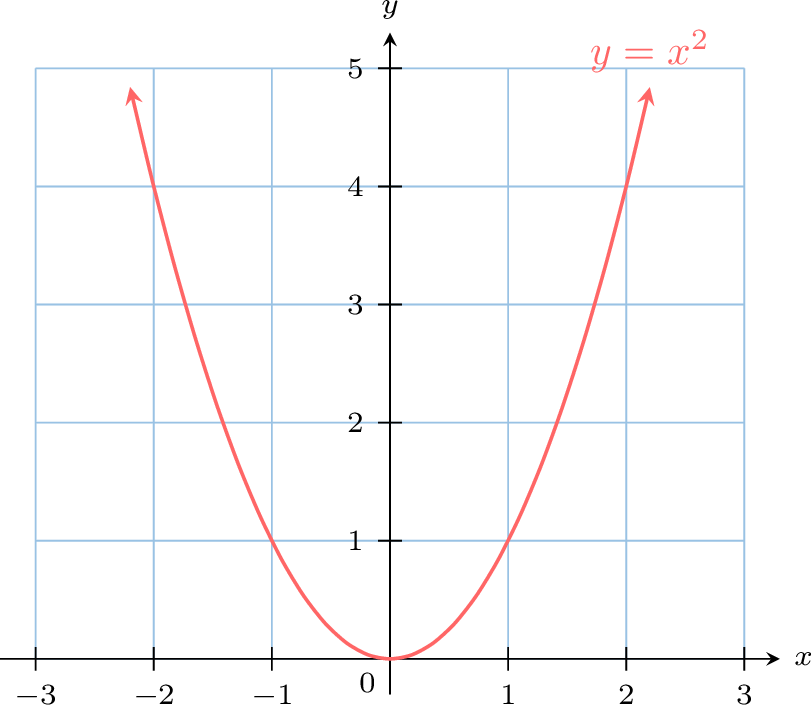

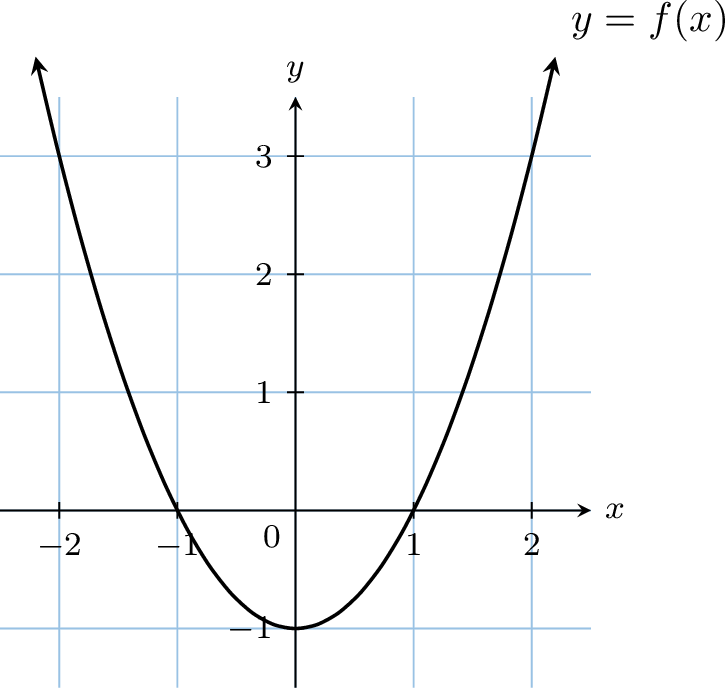

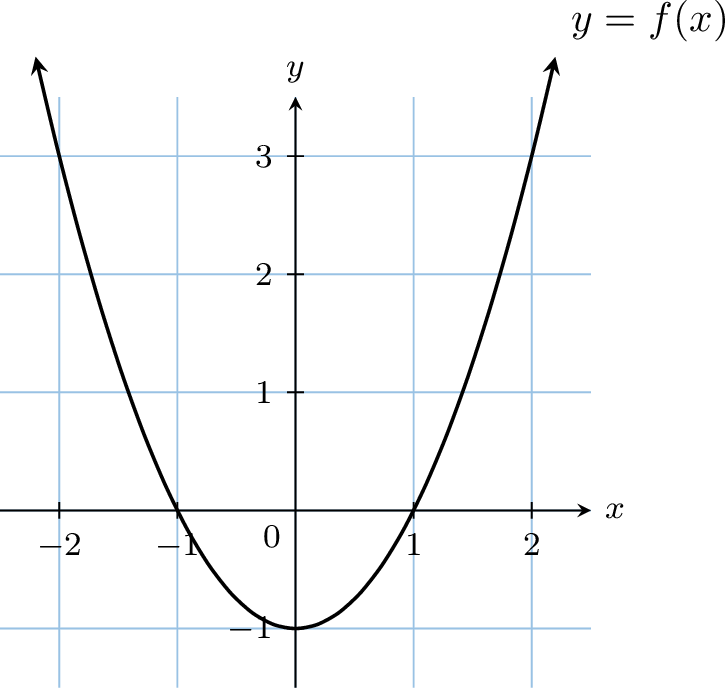

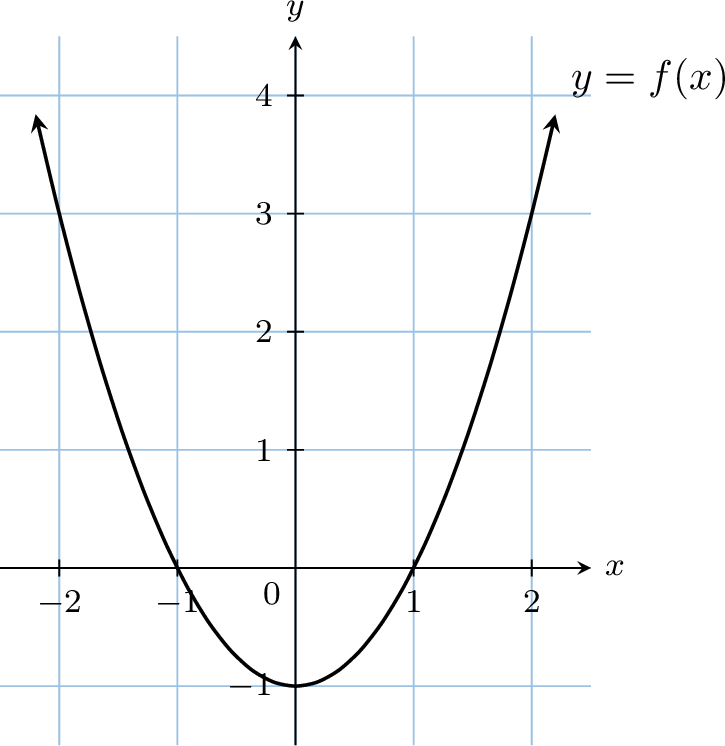

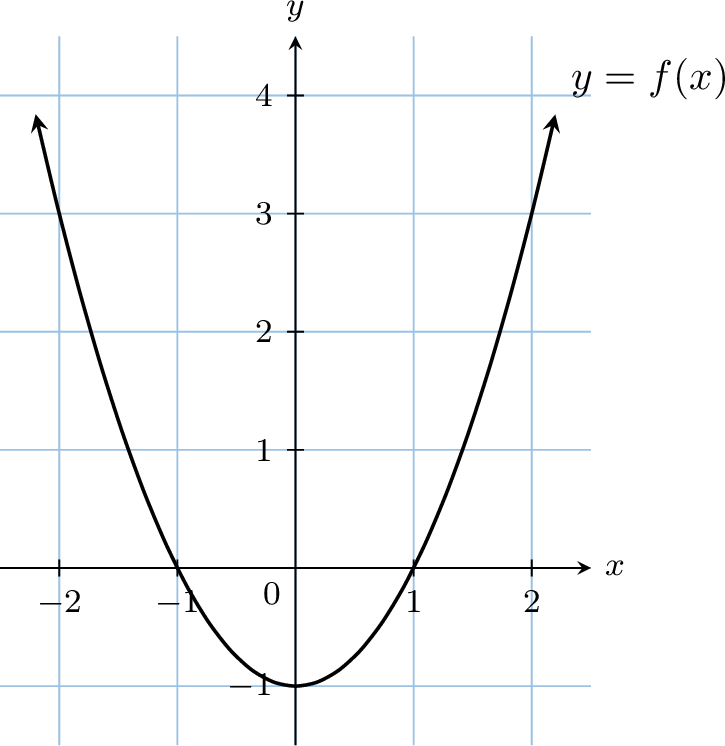

For the function \(\Function{f}{\mathbb{R}}{\mathbb{R}}{x}{x^2}\):

- The domain is \(\mathbb{R}\) (all real numbers).

- The codomain is also \(\mathbb{R}\).

- However, since \(x^2\geq 0\), the range is \([0, \infty)\), which is a subset of the codomain.

Definition Natural Domain

When a function is given by a formula and the domain is not explicitly specified, the natural domain is the largest set of real numbers for which the formula yields a defined real number.

Note

When a function's rule is given without explicitly specifying the domain and codomain, we assume the natural domain as the domain and the set of all real numbers, \(\mathbb{R}\), as the codomain.

For example, when we write \(f:x\mapsto \sqrt{x}\), we implicitly assume the domain is the set of non-negative real numbers, \([0, \infty)\), and the codomain is \(\mathbb{R}\). Thus, it is shorthand for \(\Function{f}{[0, \infty)}{\mathbb{R}}{x}{\sqrt{x}}\).

Sometimes, we simply refer to "the function \(\sqrt{x}\)". This is also a shorthand for the function defined on its natural domain.

For example, when we write \(f:x\mapsto \sqrt{x}\), we implicitly assume the domain is the set of non-negative real numbers, \([0, \infty)\), and the codomain is \(\mathbb{R}\). Thus, it is shorthand for \(\Function{f}{[0, \infty)}{\mathbb{R}}{x}{\sqrt{x}}\).

Sometimes, we simply refer to "the function \(\sqrt{x}\)". This is also a shorthand for the function defined on its natural domain.

Method Finding the Natural Domain

To find the natural domain of a function, we assume the domain is all real numbers (\(\mathbb{R}\)) and then exclude any values of \(x\) that would lead to an undefined mathematical operation. At this level, we look for restrictions caused by:

- Rational Functions: The denominator of a fraction cannot be zero. We solve `denominator = 0` to find values to exclude.

- Even Roots: The expression inside an even root (like a square root, \(\sqrt{\cdot}\), or fourth root, \(\sqrt{\cdot}\)) must be non-negative (\(\ge 0\)).

- Logarithms: The argument of a logarithm must be strictly positive (\(> 0\)). (Note: This will be covecolordef in more detail in the logarithms chapter).

Example

Find the natural domain of the function \(f:x\mapsto\frac{1}{x-2}\).

The function involves division. Division is undefined when the denominator is zero. Therefore, we must exclude any value of \(x\) that makes the denominator \(x-2\) equal to zero.

Set the denominator to zero and solve for \(x\):$$x-2 = 0 \Leftrightarrow x=2$$The natural domain is the set of all real numbers except \(2\). Using set notation, we write:$$\text{Domain} = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid x \neq 2\} \quad \text{or} \quad \mathbb{R} \setminus \{2\}$$In interval notation, this is \((-\infty, 2) \cup (2, \infty)\).

Set the denominator to zero and solve for \(x\):$$x-2 = 0 \Leftrightarrow x=2$$The natural domain is the set of all real numbers except \(2\). Using set notation, we write:$$\text{Domain} = \{x \in \mathbb{R} \mid x \neq 2\} \quad \text{or} \quad \mathbb{R} \setminus \{2\}$$In interval notation, this is \((-\infty, 2) \cup (2, \infty)\).

Tables of Values

Definition Table of Values

A table of values is a table that organizes the relationship between the input values (\(x\)) and their corresponding output values (\(f(x)\)) for a function.

Example

Complete the table of values for the function \(f:x\mapsto x^2\).

| \(x\) | \(-2\) | \(-1\) | \(0\) | \(1\) | \(2\) |

| \(f(x)\) |

We substitute each value of \(x\) into the function \(f(x)=x^2\):

- \(\begin{aligned}[t] f(-2) &= (-2)^2 \\ &= 4 \end{aligned}\)

- \(\begin{aligned}[t] f(-1) &= (-1)^2\\ &= 1 \end{aligned}\)

- \(\begin{aligned}[t] f(0) &= (0)^2 \\ &= 0 \end{aligned}\)

- \(\begin{aligned}[t] f(1) &= (1)^2 \\ &= 1 \end{aligned}\)

- \(\begin{aligned}[t] f(2) &= (2)^2 \\ &= 4 \end{aligned}\)

| \(x\) | \(-2\) | \(-1\) | \(0\) | \(1\) | \(2\) |

| \(f(x)\) | \(4\) | \(1\) | \(0\) | \(1\) | \(4\) |

Graphs

While a table of values is useful for listing some input–output pairs of a function, a graph is a powerful tool for visualizing how the output changes when the input changes. A graph gives us a picture of the function's behavior.

Definition Graph of a Function

The graph of a function \(f\) is the set of all points with coordinates \((x, f(x))\) plotted on a coordinate plane. The input, \(x\), is plotted on the horizontal axis (the x-axis), and the output, \(f(x)\), is plotted on the vertical axis (the y-axis). When we connect these points, we form the curve of the function.$$\text{Graph of } f = \{(x,f(x)): x \in X\}$$

Method Plotting a Graph from a Table

To plot the graph of a function from its table of values:

- Draw a coordinate plane with a suitable scale on each axis and label the axes.

- For each pair \((x, f(x))\) in the table, plot the corresponding point on the coordinate plane.

- If the function is defined for all \(x\) in the interval shown, connect the points with a straight line or a smooth curve.

Example

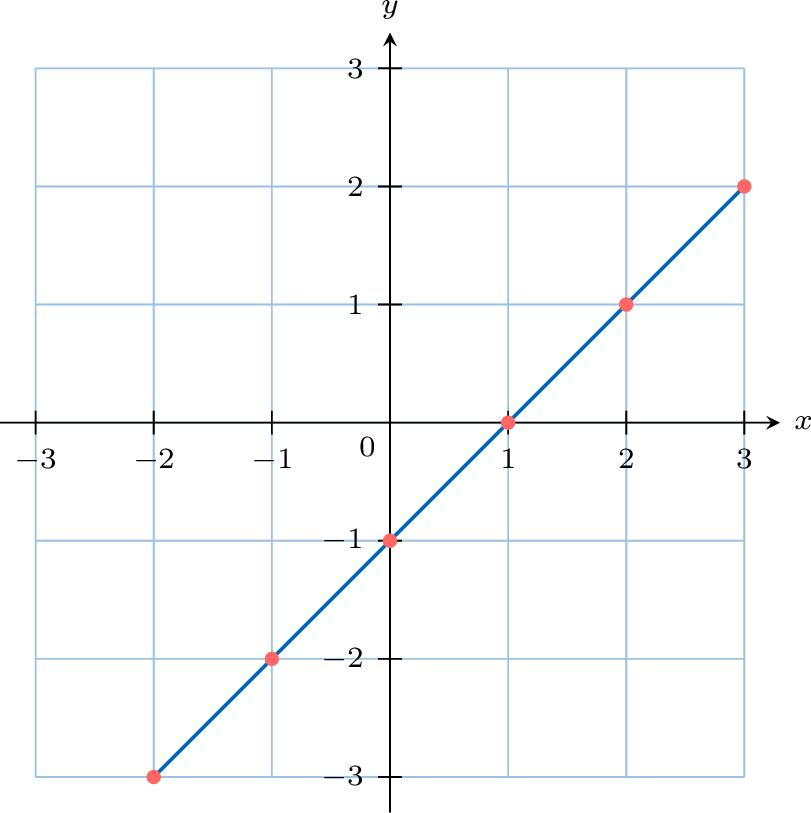

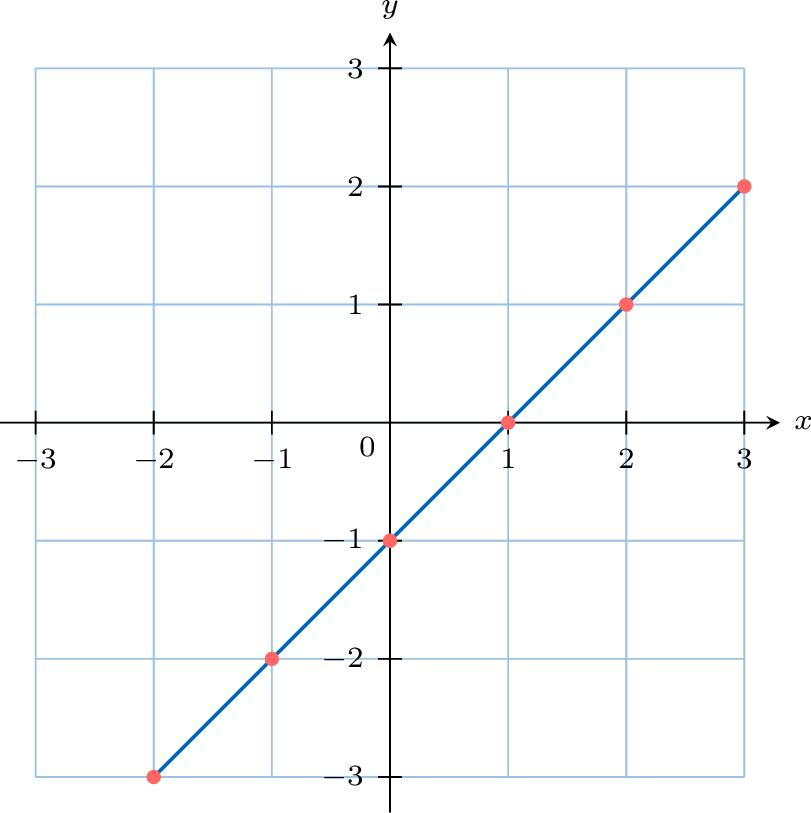

Plot the graph of the function \(f(x) = x - 1\) using its table of values.

| \(x\) | \(-2\) | \(-1\) | \(0\) | \(1\) | \(2\) | \(3\) |

| \(f(x)\) | \(-3\) | \(-2\) | \(-1\) | \(0\) | \(1\) | \(2\) |

We plot the points \((-2, -3)\), \((-1, -2)\), \((0, -1)\), \((1, 0)\), \((2, 1)\), and \((3, 2)\) from the table. These points lie on the same straight line, so we connect them to draw the graph of \(f(x)=x-1\).

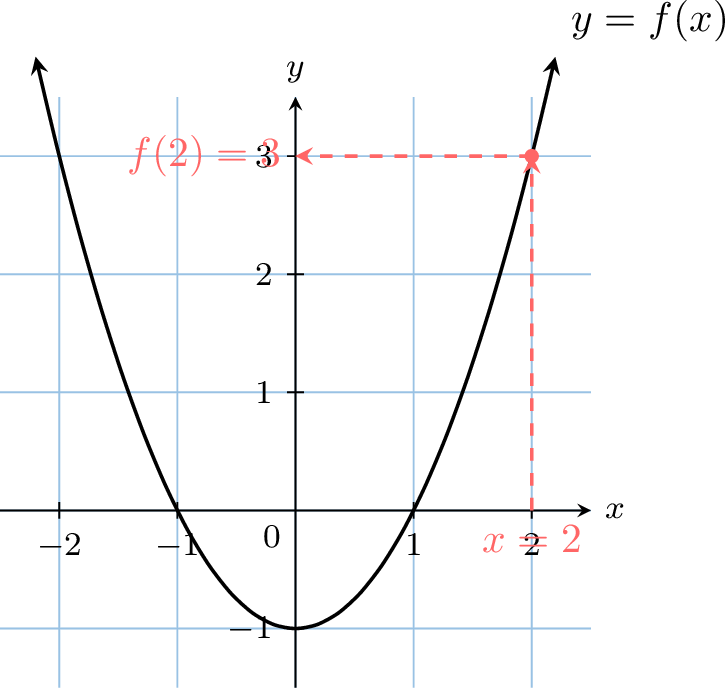

Method Finding the Value of \(f(x)\) from a Graph

To find the output \(f(x)\) for a given input \(x\) using a graph:

- Locate the input value on the horizontal x-axis.

- Move vertically from that point until you reach the curve of the function.

- Move horizontally from the intersection point to the vertical y-axis and read the corresponding value. This y-value is the output \(f(x)\).

Example

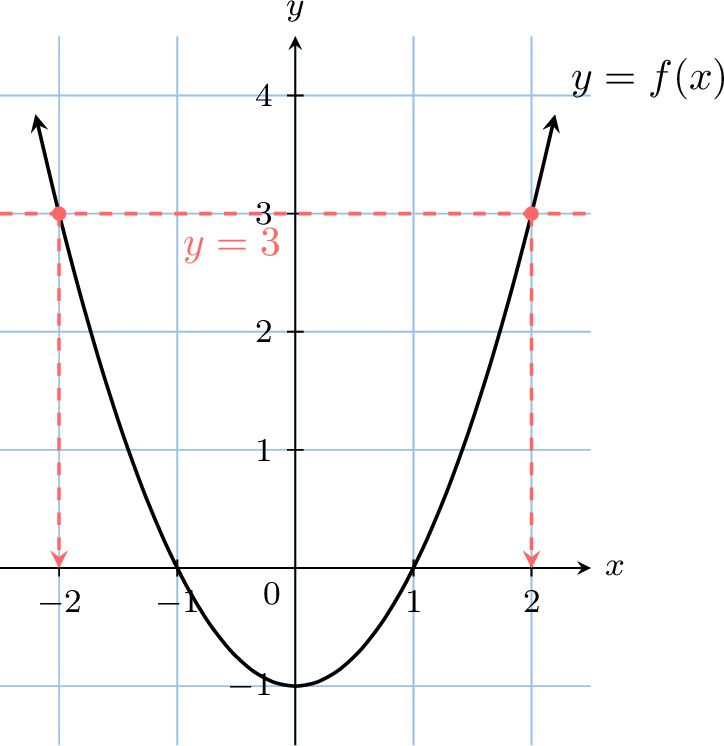

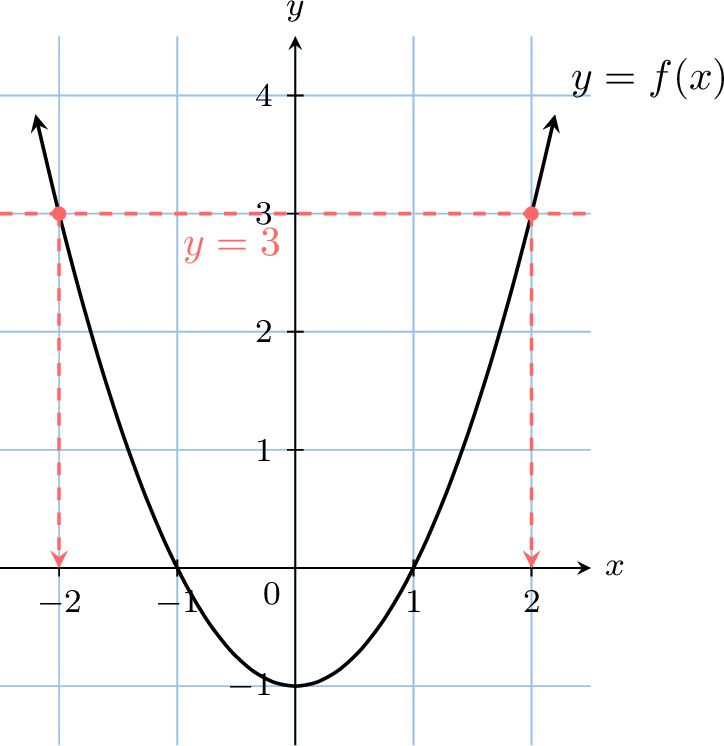

Using the graph of the function \(f\) below, find the value of \(f(2)\).

We follow the graphical method:

- Start at \(x=2\) on the horizontal axis.

- Move up to meet the curve.

- Move horizontally to the vertical axis and read the value, which is \(3\).

We have learned how to take an input (\(x\)) and find its output (\(f(x)\)). Now, we will learn how to work backwards: if we know the output, can we find the input(s) that produced it? This process is called finding the preimage(s) (or input(s)) of a given value.

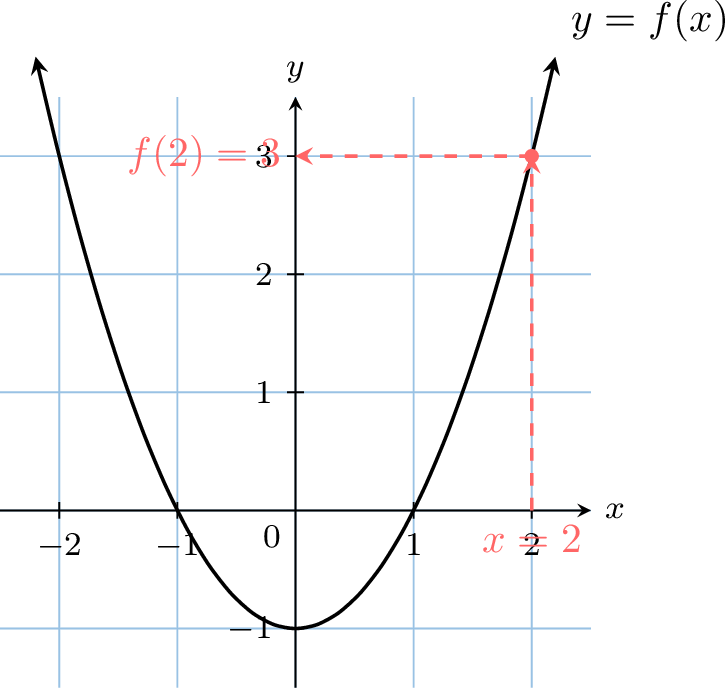

Method Finding Inputs from Outputs on a Graph

To find the preimage(s) of a value \(y\) (i.e., find all \(x\) such that \(f(x)=y\)):

- Locate the output value \(y\) on the vertical y-axis.

- Draw a horizontal line from this value across the graph.

- Find the intersection point(s) where the horizontal line crosses the function's curve.

- Move vertically to the x-axis from each intersection point to read the corresponding input value(s). These are the preimages.

Example

Using the graph of the function \(f\) below, find \(x\) such that \(f(x)= 3\).

We apply the graphical method:

The preimages of \(3\) are \(\boldsymbol{-2}\) and \(\boldsymbol{2}\).

- We locate \(y=3\) on the vertical axis.

- We draw a horizontal line at \(y=3\).

- The line intersects the curve at two points.

- We move vertically from these points to the x-axis to read the values, which are \(-2\) and \(2\).

Finding a preimage graphically is useful for visualization, but for an exact answer, we can use algebra.

Bijective Functions

For a function to be perfectly reversible (i.e., to have an inverse), it must create a perfect pairing between the elements of its domain and its codomain. This leads to the concept of a bijection, which is a function that is both injective and surjective.

Definition Injective, Surjective, and Bijective Functions

Let \(f: X \to Y\) be a function.

- \(f\) is injective (one-to-one) if different inputs produce different outputs. For any \(x_1, x_2 \in X\), if \(x_1 \neq x_2\), then \(f(x_1) \neq f(x_2)\).

- \(f\) is surjective (onto) if its range is equal to its codomain (\(f(X)=Y\)). This means every element in the codomain \(Y\) is the image of at least one element from the domain \(X\).

- \(f\) is bijective if it is both injective and surjective. This means every element in the codomain is the image of exactly one element from the domain.

Example

Consider two versions of the squaring function:

- \(\Function{f}{\mathbb{R}}{\mathbb{R}}{x}{x^2}\)

- \(\Function{g}{[0,\infty)}{[0,\infty)}{x}{x^2}\)

- The function \(f\) is not bijective. It is not injective because \(f(-2)=f(2)\). It is not surjective because its range, \([0, \infty)\), is not equal to its codomain, \(\mathbb{R}\).

- The function \(g\) is bijective. It is injective because its domain is restricted to non-negative numbers. It is surjective because its range, \([0, \infty)\), is equal to its specified codomain, \([0, \infty)\).

Method The Horizontal Line Test for Bijectivity

To determine visually if a function \(f: X \to Y\) is bijective:

- Draw the graph of the function \(f(x)\).

- Imagine drawing horizontal lines across the graph for every possible \(y\)-value in the codomain \(Y\).

- Conclusion:

- The function is bijective if and only if every horizontal line (for all \(y \in Y\)) intersects the graph exactly once.

- Intersecting at most once shows it is injective.

- Intersecting at least once shows it is surjective.

- The function is bijective if and only if every horizontal line (for all \(y \in Y\)) intersects the graph exactly once.

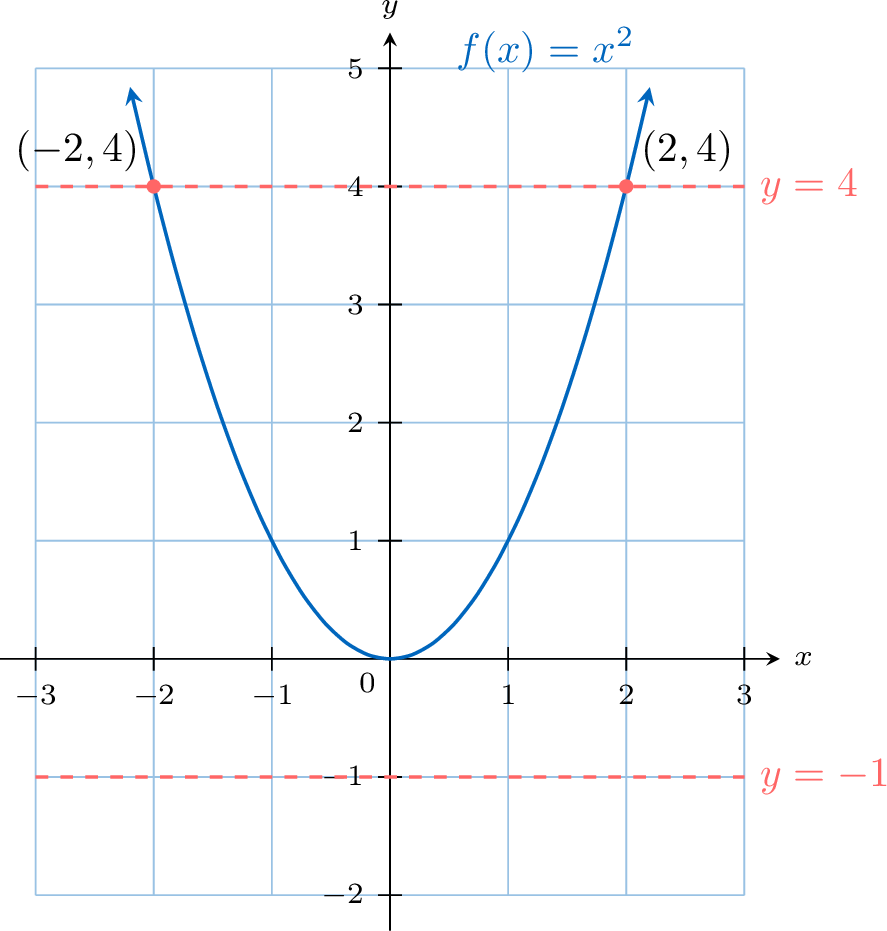

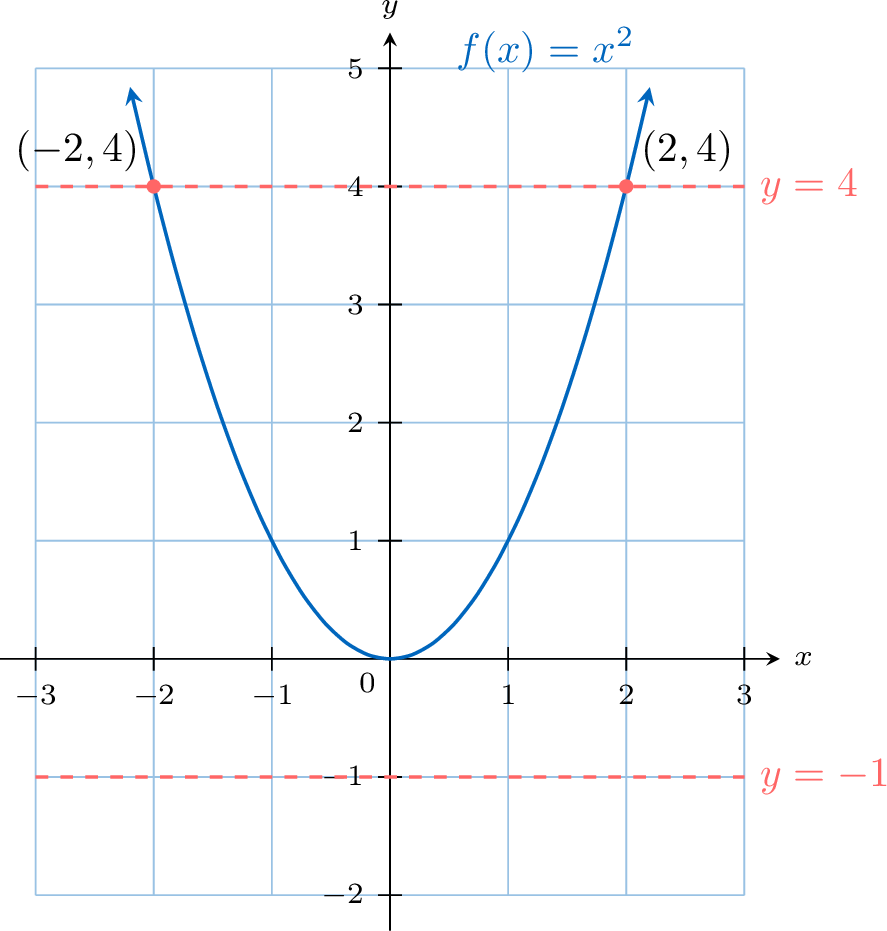

Example

Use the horizontal line test to determine if the function \(\Function{f}{\mathbb{R}}{\mathbb{R}}{x}{x^2}\) is a bijective function.

First, we graph the function \(f(x) = x^2\). The specified codomain is \(\mathbb{R}\).

- Injectivity: The horizontal line \(y=4\) intersects the graph at two distinct points, \((-2,4)\) and \((2,4)\). Since a horizontal line intersects the graph more than once, the function is not injective.

- Surjectivity: The horizontal line \(y=-1\) is in the codomain (\(\mathbb{R}\)) but does not intersect the graph at all. This means that \(-1\) has no preimage. Since there is an element in the codomain that is not in the range, the function is not surjective.

Operations on Functions

Algebra of Functions

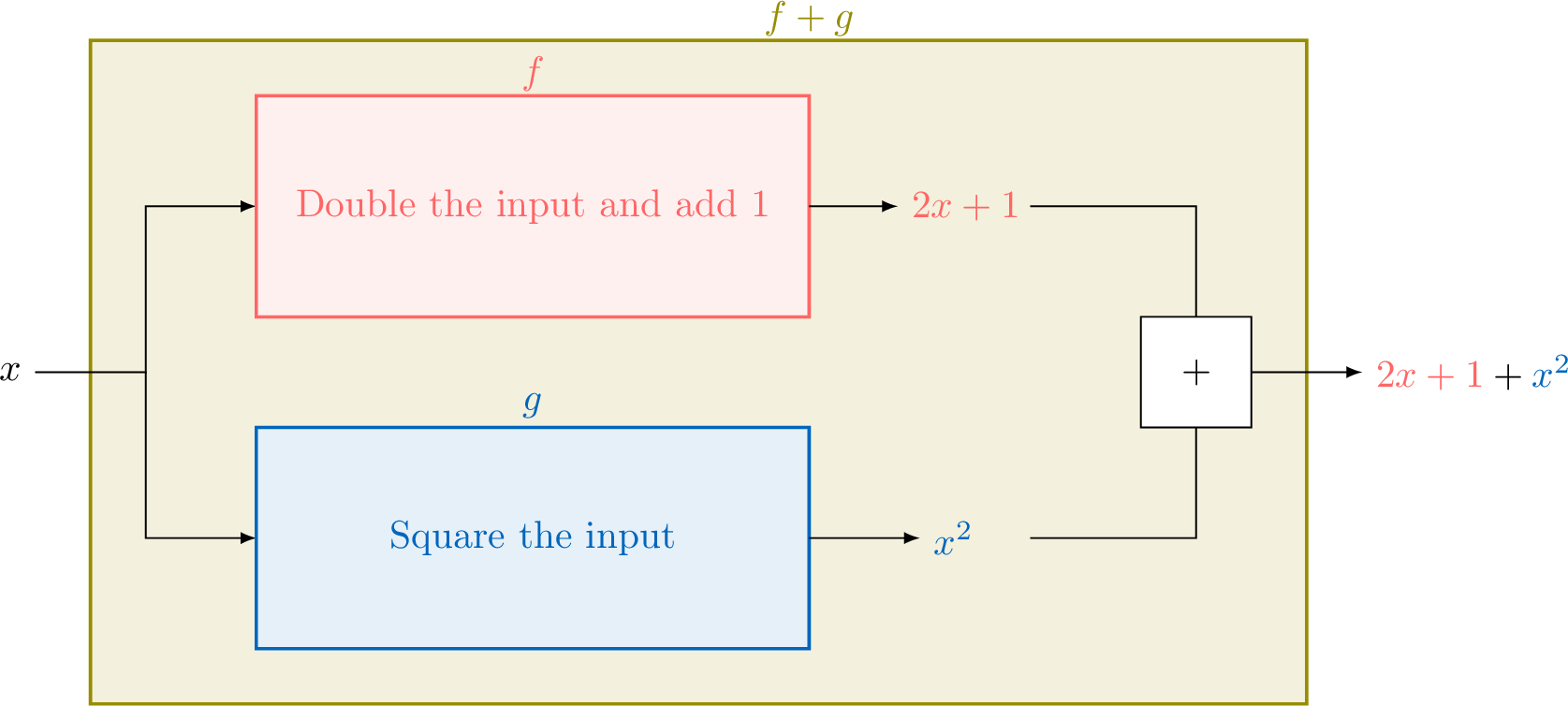

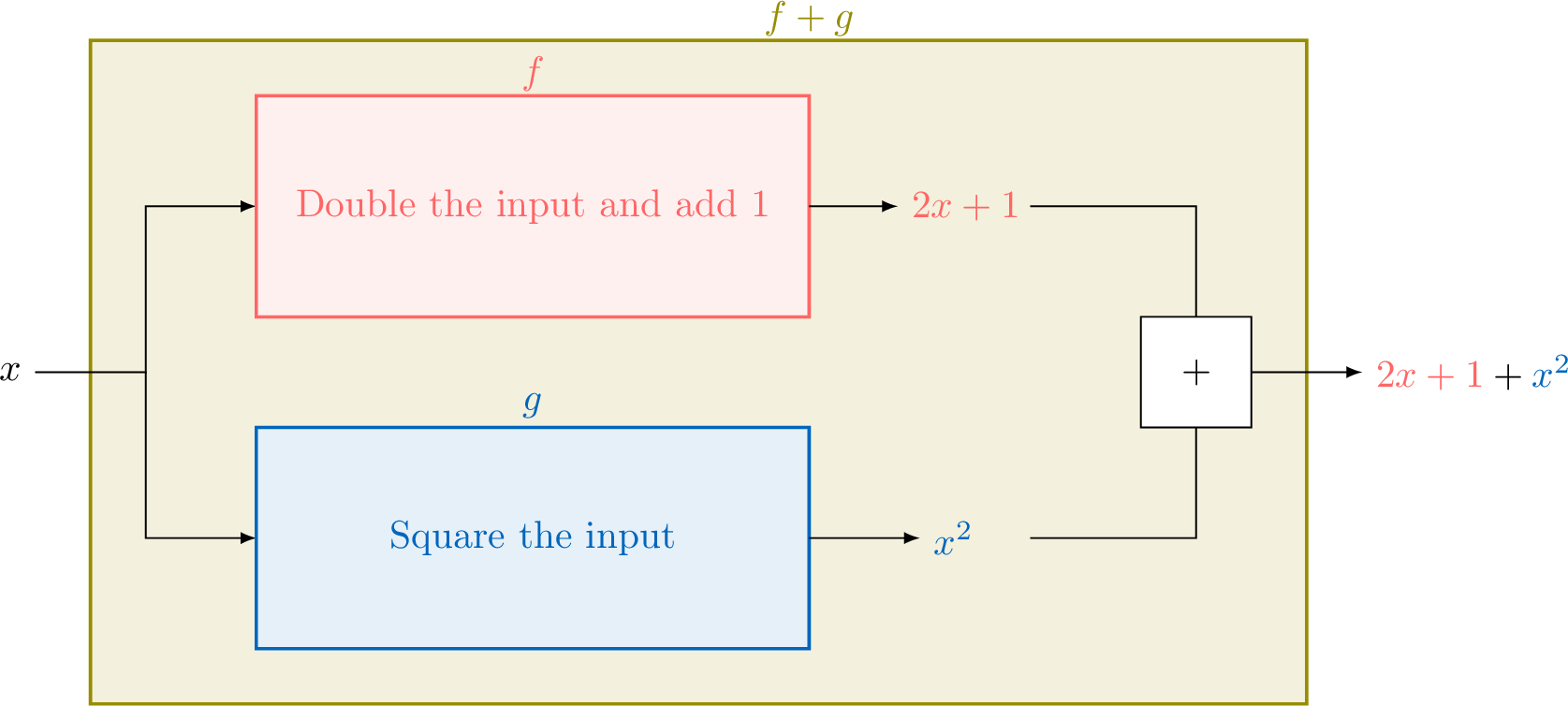

Let \(\textcolor{colordef}{f(x)=2x+1}\) and \(\textcolor{colorprop}{g(x)=x^2}\).

\(\textcolor{olive}{(f+g)(x)}\) means that, for any input \(x\) that belongs to the domains of both functions, you calculate \(\textcolor{colordef}{f(x)}\) and \(\textcolor{colorprop}{g(x)}\) separately, then add the results. In other words, \((f+g)\) is a new function defined by \((f+g)(x)=f(x)+g(x)\).

This is illustrated by the function machine below:

\(\textcolor{olive}{(f+g)(x)}\) means that, for any input \(x\) that belongs to the domains of both functions, you calculate \(\textcolor{colordef}{f(x)}\) and \(\textcolor{colorprop}{g(x)}\) separately, then add the results. In other words, \((f+g)\) is a new function defined by \((f+g)(x)=f(x)+g(x)\).

This is illustrated by the function machine below:

Definition Operations on Functions

Given two functions \(f\) and \(g\), we can define new functions by performing arithmetic operations on their outputs, for each \(x\) where both are defined:

For the quotient, the domain is the intersection of the domains of \(f\) and \(g\), excluding any \(x\) such that \(g(x)=0\).

- Sum: \((f+g)(x) = f(x) + g(x)\)

- Difference: \((f-g)(x) = f(x) - g(x)\)

- Product: \((fg)(x) = f(x) \times g(x)\)

- Quotient: \(\displaystyle\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)(x) = \frac{f(x)}{g(x)}\), provided that \(g(x) \neq 0\).

For the quotient, the domain is the intersection of the domains of \(f\) and \(g\), excluding any \(x\) such that \(g(x)=0\).

Example

Let \(f(x)=2x+1\) and \(g(x)=x^4-1\). Find \((f+g)(x)\).

\(\begin{aligned}(f+g)(x) &= f(x) + g(x) \\ &= (2x+1) + (x^4-1) \\ &= x^4 + 2x.\end{aligned}\)

Since both \(f\) and \(g\) are polynomials, \((f+g)(x)\) is defined for all real numbers \(x\).

Since both \(f\) and \(g\) are polynomials, \((f+g)(x)\) is defined for all real numbers \(x\).

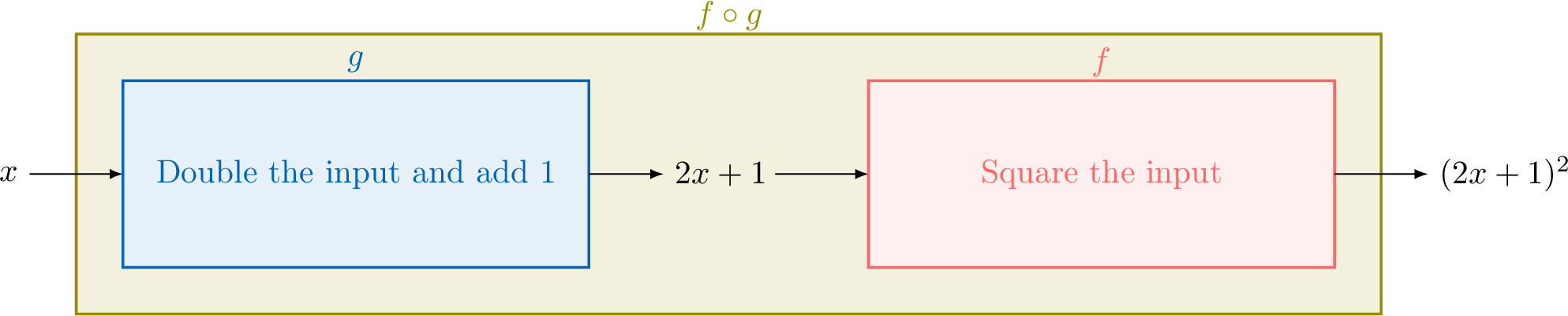

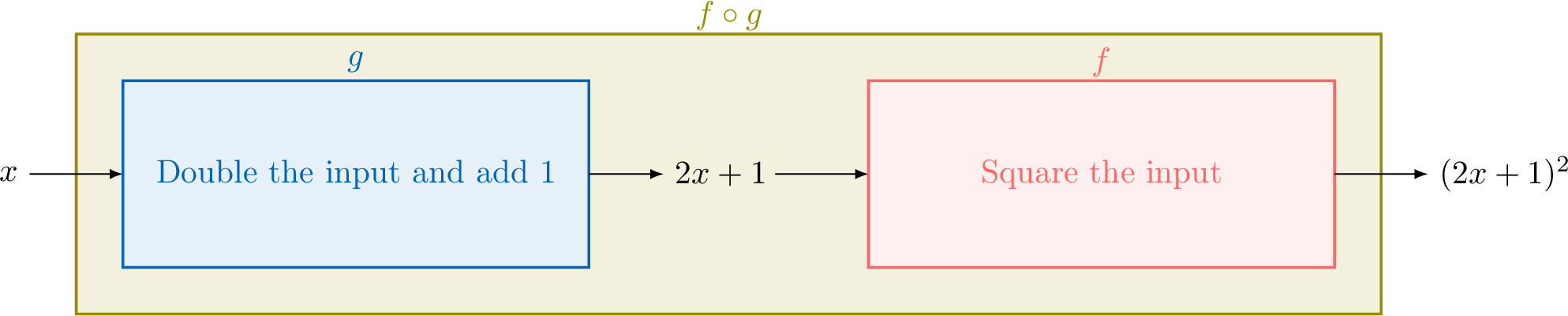

Composition of Functions

Let \(\textcolor{colordef}{f(x)=x^2}\) and \(\textcolor{colorprop}{g(x)=2x+1}\).

The composition \(\textcolor{olive}{(f \circ g)(x)}\) means that you first apply \(g\) to \(x\), and then apply \(f\) to the result. In other words, \(x\) goes through machine \(g\) (becoming \(2x+1\)), and that output then goes through machine \(f\).

The composition \(\textcolor{olive}{(f \circ g)(x)}\) means that you first apply \(g\) to \(x\), and then apply \(f\) to the result. In other words, \(x\) goes through machine \(g\) (becoming \(2x+1\)), and that output then goes through machine \(f\).

Definition Composition of Functions

Given two functions \(f\) and \(g\), the composite function, denoted \(\boldsymbol{f \circ g}\) (read "\(f\) composed with \(g\)"), is defined by:$$\boldsymbol{(f \circ g)(x) = f(g(x))}$$for every \(x\) that belongs to the domain of \(g\) and for which \(g(x)\) belongs to the domain of \(f\).

We first apply the function \(g\) to \(x\), and then apply the function \(f\) to the result \(g(x)\).

We first apply the function \(g\) to \(x\), and then apply the function \(f\) to the result \(g(x)\).

Example

Let \(f(x)=x^2\) and \(g(x)=2x+1\).

- Find \((f \circ g)(x)\).

- Find \((g \circ f)(x)\).

- Is composition commutative? (i.e., is \((f \circ g)(x) = (g \circ f)(x)\)?)

- \(\begin{aligned}[t] (f \circ g)(x) &= f(g(x)) \\ &= f(2x+1) \\ &= (2x+1)^2 \\ &= 4x^2 + 4x + 1. \end{aligned}\)

- \(\begin{aligned}[t] (g \circ f)(x) &= g(f(x)) \\ &= g(x^2) \\ &= 2(x^2) + 1 \\ &= 2x^2 + 1. \end{aligned}\)

- No. Since \(4x^2 + 4x + 1 \neq 2x^2 + 1\), the two composite functions are different, so function composition is not commutative in general.

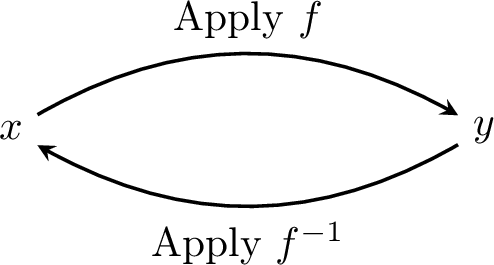

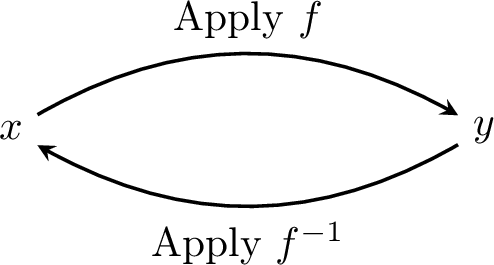

Inverse Functions

In arithmetic, we are familiar with inverse operations. For example, subtraction is the inverse of addition because it "undoes" the addition. If you start with 5, add 3 to get 8, and then subtract 3, you return to 5:$$(5+3) - 3 = 5.$$Similarly, division is the inverse of multiplication:$$(5\times 3) \div 3 = 5.$$The concept of an inverse function follows the same idea. An inverse function, denoted \(\boldsymbol{f^{-1}}\), is a function that "undoes" or reverses the action of another function, \(f\).

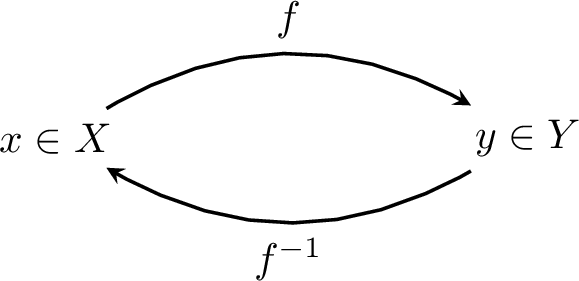

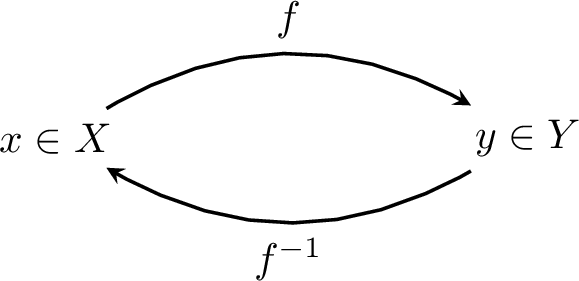

If a function \(f\) takes an input \(x\) to an output \(y\), the inverse function \(f^{-1}\) takes that output \(y\) back to the original input \(x\). This creates a perfect loop:

If a function \(f\) takes an input \(x\) to an output \(y\), the inverse function \(f^{-1}\) takes that output \(y\) back to the original input \(x\). This creates a perfect loop:

Definition Inverse Function

Let \(f: X \to Y\) be a bijective function.

The inverse function, denoted \(f^{-1}\), is the function \(\boldsymbol{f^{-1}: Y \to X}\) that reverses the action of \(f\).

This means that if \(f\) maps an input \(x\) to an output \(y\), then \(f^{-1}\) maps that output \(y\) back to the original input \(x\). This relationship is defined by:$$ f(x) = y \iff f^{-1}(y) = x $$

The inverse function, denoted \(f^{-1}\), is the function \(\boldsymbol{f^{-1}: Y \to X}\) that reverses the action of \(f\).

This means that if \(f\) maps an input \(x\) to an output \(y\), then \(f^{-1}\) maps that output \(y\) back to the original input \(x\). This relationship is defined by:$$ f(x) = y \iff f^{-1}(y) = x $$

- \(\boldsymbol{(f^{-1} \circ f)(x) = x}\) for all \(x\) in the domain of \(f\) (\(X\)).

- \(\boldsymbol{(f \circ f^{-1})(y) = y}\) for all \(y\) in the domain of \(f^{-1}\) (\(Y\)).

Method Finding the Inverse Function

To find the inverse of a function \(f\) (when it exists):

- Set \(y = f(x)\).

- Solve the equation for \(x\) in terms of \(y\). This gives an expression of the form \(x = f^{-1}(y)\).

- Swap the variables \(x\) and \(y\) to write the inverse in terms of \(x\). The result is \(y = f^{-1}(x)\).

Example

Find the inverse of the function \(\Function{f}{[0,\infty)}{[0,\infty)}{x}{\sqrt{x}}\).

The function is \(f(x) = \sqrt{x}\) with Domain: \([0, \infty)\) and Range: \([0, \infty)\).

- Set \(y = \sqrt{x}\).

- Solve for \(x\): Since the domain of \(f\) is non-negative, \(x \ge 0\), and the range is non-negative, \(y \ge 0\). We can square both sides: $$ y^2 = x \Leftrightarrow x = y^2 $$

- Swap variables to get the rule: \(y = x^2\).

- The domain of \(f^{-1}\) is the range of \(f\), which is \([0, \infty)\). The range of \(f^{-1}\) is the domain of \(f\), which is \([0, \infty)\).

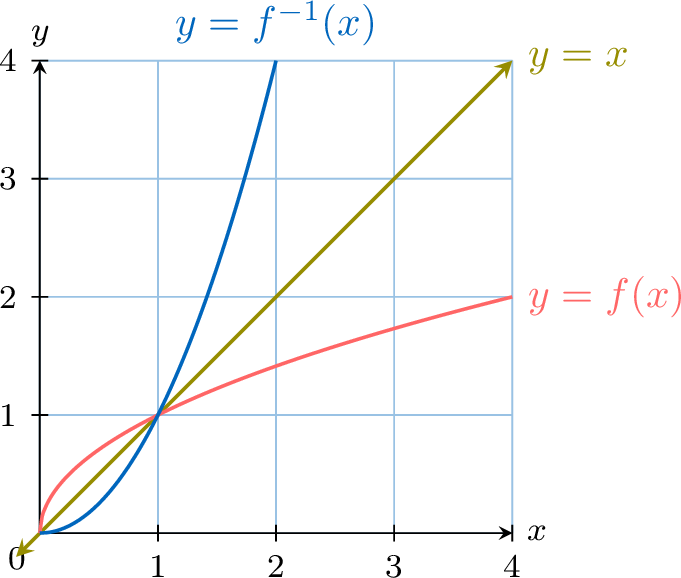

Proposition Symmetry of Inverse Functions

The graph of a function \(f\) and its inverse \(f^{-1}\) are reflections of each other across the line \(\boldsymbol{y = x}\).