Exponential Functions

In previous chapters, we learned how to evaluate expressions like \(a^n\), where the exponent \(n\) was an integer or a rational number. This chapter extends that concept to the exponential function, written as \(f(x) = a^x\), where the exponent \(x\) can be any real number.

We will explore the key features and graphs of these functions and see how they are used to model real-world phenomena involving rapid growth or decay, such as population dynamics and compound interest.

We will explore the key features and graphs of these functions and see how they are used to model real-world phenomena involving rapid growth or decay, such as population dynamics and compound interest.

Exponential Function

Definition Exponential Function

The exponential function has the form \(f(x)=a^x\), where the base \(a\) is a positive constant and \(a \neq 1\).

Proposition Key Features of the Graph of \(y\equal a^x\)

All exponential functions of the form \(f(x) = a^x\) share several key graphical features: \(\quad\)

\(\quad\)

- Domain: The domain is all real numbers, \((-\infty, \infty)\).

- Range: The range is all positive real numbers, \((0, \infty)\).

- Horizontal Asymptote: The graph has a horizontal asymptote at the x-axis (\(y=0\)). The function approaches this line but never touches it.

- y-intercept: The graph always passes through the point \((0, 1)\), because \(a^0 = 1\) for any valid base \(a\).

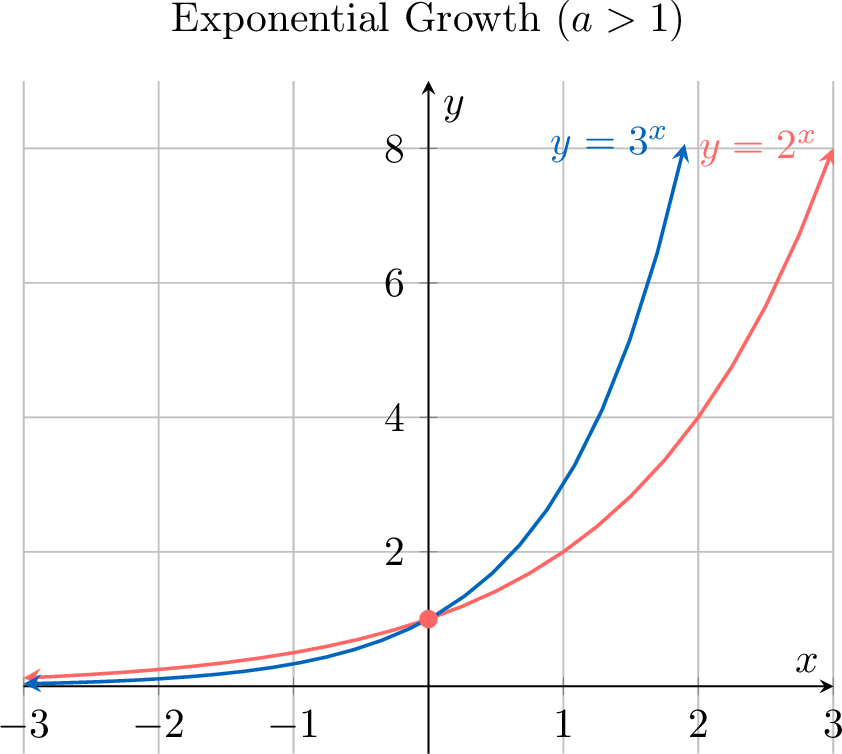

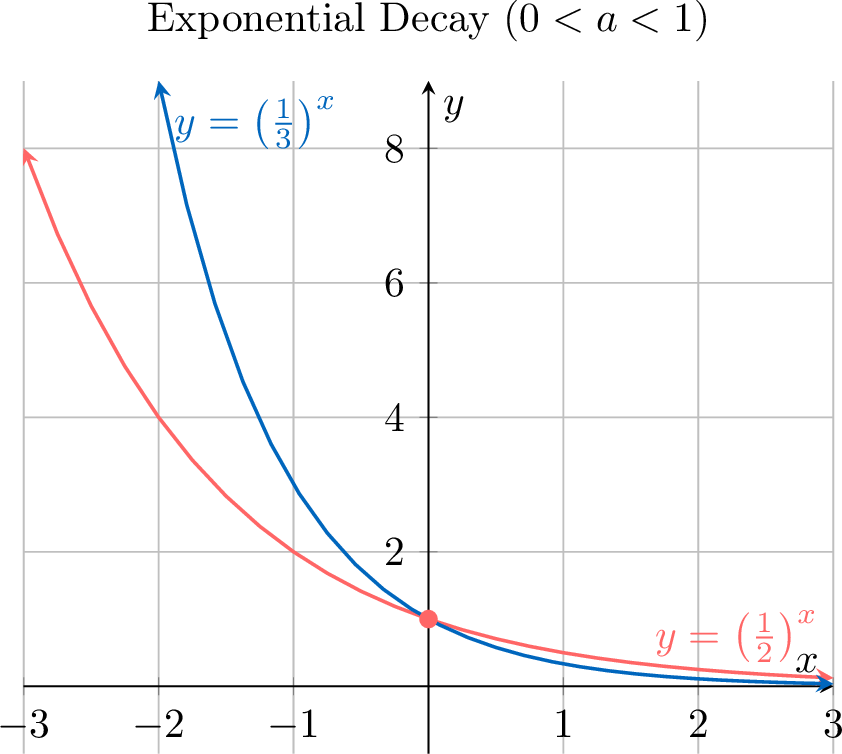

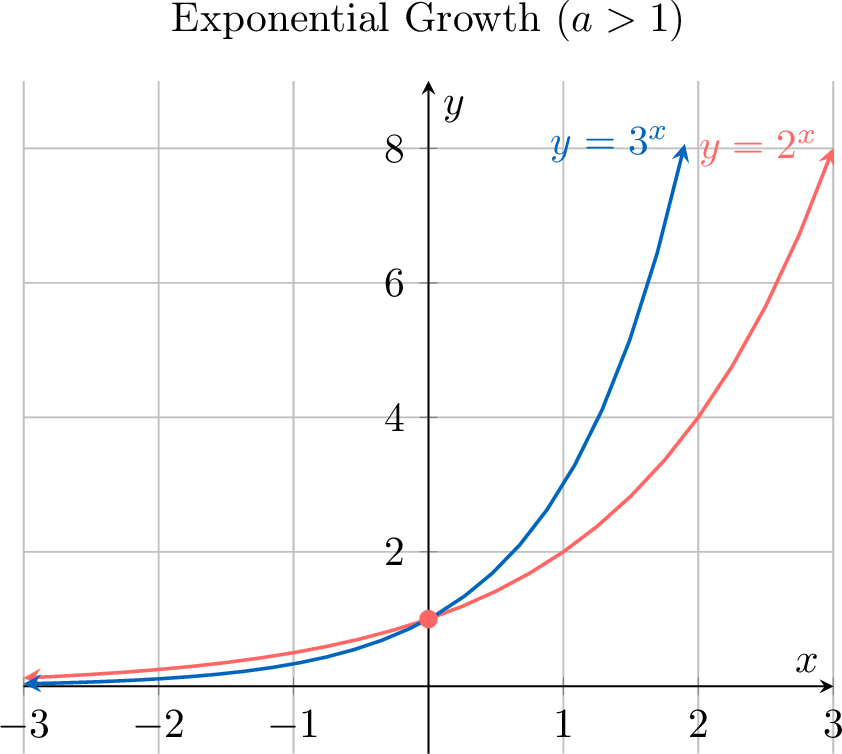

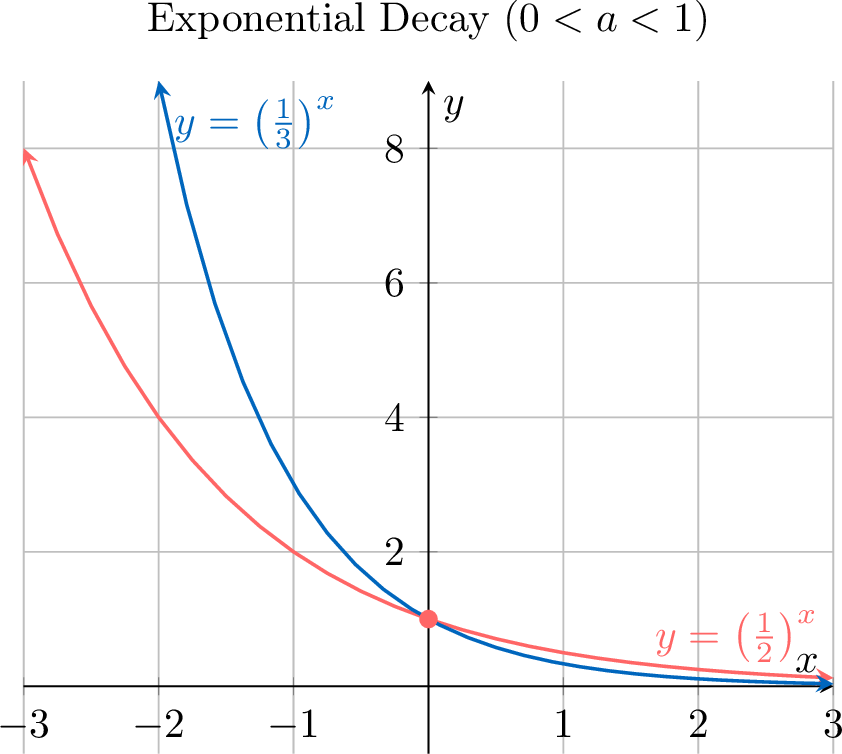

- General Shape: The shape of the graph is determined by the value of the base, \(a\):

- If \(a > 1\), the function shows exponential growth and is increasing.

- If \(0 < a < 1\), the function shows exponential decay and is decreasing.

\(\quad\)

\(\quad\)

Exponential vs. Linear Relationships

Many real-world patterns of growth and decay can be modeled by either linear or exponential functions. The key to distinguishing between them is understanding how the quantity changes over regular intervals.

- Linear relationships involve additive change. The same amount is added or subtracted in each time step. Think of saving \(\dollar\) 50 every month.

- Exponential relationships involve multiplicative change. The amount is multiplied by the same factor in each time step. Think of a population that doubles every year.

Proposition Identifying Linear vs. Exponential Relationships

For a set of data where the independent variable (\(x\)) increases by constant intervals:

- If the difference between consecutive dependent variable (\(y\)) values is constant, the relationship is linear.

- If the ratio of consecutive dependent variable (\(y\)) values is constant, the relationship is exponential.

- Linear Relationship:

Let the linear relationship be \(y = ax + b\).

Consider two points, \((x_1, y_1)\) and \((x_2, y_2)\), such that the difference in their \(x\)-values is a constant, \(k\).

So, \(x_2 - x_1 = k\).

The corresponding \(y\)-values are \(y_1 = ax_1 + b\) and \(y_2 = ax_2 + b\).

The difference between these \(y\)-values is:$$ \begin{aligned}[t]y_2 - y_1 &= (ax_2 + b) - (ax_1 + b) \\ &= ax_2 - ax_1 \\ &= a(x_2 - x_1) \\ &= ak\end{aligned} $$Since both \(a\) (the slope) and \(k\) (the change in \(x\)) are constants, the difference \(y_2 - y_1\) is also a constant. - Exponential Relationship:

Let the exponential relationship be \(y = c \cdot a^x\).

Consider two points, \((x_1, y_1)\) and \((x_2, y_2)\), such that the difference in their \(x\)-values is a constant, \(k\).

So, \(x_2 - x_1 = k\).

The corresponding \(y\)-values are \(y_1 = c \cdot a^{x_1}\) and \(y_2 = c \cdot a^{x_2}\).

The ratio of these \(y\)-values is:$$ \begin{aligned}[t]\frac{y_2}{y_1} &= \frac{c \cdot a^{x_2}}{c \cdot a^{x_1}} \\ &= a^{x_2 - x_1} \\ &= a^k\end{aligned} $$Since both \(a\) (the base) and \(k\) (the change in \(x\)) are constants, the ratio \(\frac{y_2}{y_1}\) is also a constant. This constant is often called the common ratio.

Method Analyzing Data in a Table

To determine if a relationship is linear or exponential from a table of values:

- Ensure the \(x\)-values increase by a constant step.

- Check for a common difference: Calculate the difference between consecutive \(y\)-values (\(y_2 - y_1\), \(y_3 - y_2\), etc.). If this value is constant, the relationship is linear.

- Check for a common ratio: If the difference is not constant, calculate the ratio of consecutive \(y\)-values (\(\frac{y_2}{y_1}\), \(\frac{y_3}{y_2}\), etc.). If this value is constant, the relationship is exponential.

Example

Consider the relationship represented by this table:

| \(x\) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| \(y\) | 5 | 8 | 11 | 14 |

The \(x\)-values increase by a constant step of 1.

We check for a common difference between consecutive \(y\)-values:

We check for a common difference between consecutive \(y\)-values:

- \(y_2 - y_1 = 8 - 5 = \boldsymbol{3}\)

- \(y_3 - y_2 = 11 - 8 = \boldsymbol{3}\)

- \(y_4 - y_3 = 14 - 11 = \boldsymbol{3}\)

Example

Consider the relationship represented by this table:

| \(x\) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| \(y\) | 2 | 6 | 18 | 54 |

The \(x\)-values increase by a constant step of 1.

First, we check for a common difference: \(6-2=4\), but \(18-6=12\). The difference is not constant, so the relationship is not linear.

Next, we check for a common ratio between consecutive \(y\)-values:

First, we check for a common difference: \(6-2=4\), but \(18-6=12\). The difference is not constant, so the relationship is not linear.

Next, we check for a common ratio between consecutive \(y\)-values:

- \(\frac{y_2}{y_1} = \frac{6}{2} = \boldsymbol{3}\)

- \(\frac{y_3}{y_2} = \frac{18}{6} = \boldsymbol{3}\)

- \(\frac{y_4}{y_3} = \frac{54}{18} = \boldsymbol{3}\)

Exponential Models

Exponential functions are used to model quantities that change by a constant multiplicative factor over equal intervals of time. This core principle distinguishes them from linear functions, which change by a constant difference (addition or subtraction).

There are two main types of exponential models:

There are two main types of exponential models:

- Exponential Growth: The quantity increases by a constant factor greater than 1. This is seen in phenomena like population growth and compound interest.

- Exponential Decay: The quantity decreases by a constant factor between 0 and 1. This is seen in phenomena like radioactive decay and asset depreciation.

Definition General Model for Exponential Growth and Decay

An exponential relationship is described by the function:$$ A(t) = A_0 \times R^t $$where:

- \(A(t)\) is the amount at time \(t\).

- \(A_0\) is the initial amount (the amount at \(t=0\)).

- \(R\) is the constant growth or decay factor per unit of time.

- \(t\) is the time elapsed.

Example

The population of foxes, \(P\), in a specified area, \(t\) years after observation began, is modeled by the equation: \(P(t)=300(1.25)^t\).

- How many foxes are there initially?

- What is the annual percentage growth rate?

- How many foxes are there after 5 years?

- The initial population corresponds to \(t=0\). $$P(0) = 300(1.25)^0 = 300 \times 1 = \boldsymbol{300} \text{ foxes}$$

- The growth factor is \(R=1.25\). Since \(R = 1+r\), we have \(1.25 = 1+r\), which gives \(r=0.25\).

The annual growth rate is \(\boldsymbol{25\pourcent}\). - Substitute \(t=5\) into the equation. Since the population must be a whole number, we round to the nearest fox. $$P(5) = 300(1.25)^5 \approx 915.52... \approx \boldsymbol{916} \text{ foxes}$$

Example

An amount of \(\dollar 5\,000\) is invested at \(6\pourcent\) p.a. compounded annually.

- Find a model for the amount, \(A\), after \(t\) years.

- Find the amount after 4 years.

- The initial amount is \(A_0 = 5\,000\). The annual interest rate is \(r = 0.06\).

The growth factor is \(R = 1+r = 1+0.06 = 1.06\).

The model is \(\boldsymbol{A(t) = 5\,000(1.06)^t}\). - After 4 years, the amount is: $$A(4) = 5\,000(1.06)^4 \approx 6\,312.38...$$ The amount is \(\boldsymbol{\dollar 6\,312.38}\).