Roots

Square Roots

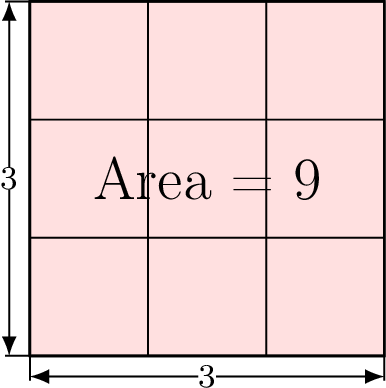

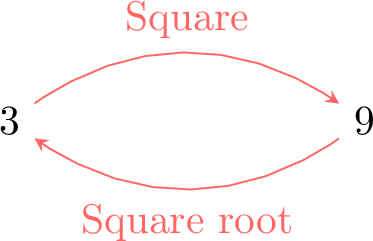

- When we square a number, we multiply it by itself. For example, \(3\) squared is \(3 \times 3\), which we write as \(3^2\).

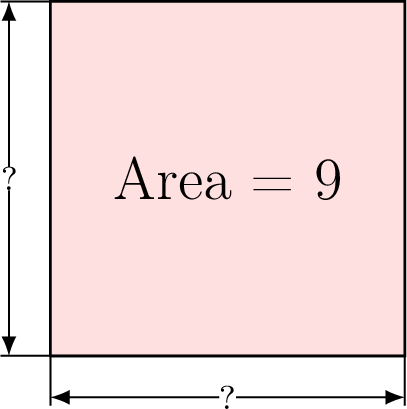

\(3^2 = 9\). The area of a square with side length \(3\) is \(9\) square units. - The square root is the inverse operation: it undoes squaring.

Definition Square root

The square root of a non-negative number \(a\) (that is, \(a \ge 0\)), written as \(\sqrt{a}\), is the non-negative number that, when multiplied by itself, gives \(a\).$$\left(\sqrt{a}\right)^2 = a$$

Note

- The square root symbol \(\sqrt{\quad}\) always asks for the positive root. For example, \(\sqrt{25} = 5\). It is a common mistake to think that \(\sqrt{25}\) is \(\pm 5\).

While it's true that both \(5^2 = 25\) and \((-5)^2 = 25\), the symbol \(\sqrt{25}\) refers only to the positive solution, which is \(5\). - Why can't we take the square root of a negative number (in the real numbers)?

Consider \(\sqrt{-9}\). To find this value, we need a number that, when multiplied by itself, gives \(-9\).- A positive number squared is positive (\(3 \times 3 = 9\)).

- A negative number squared is also positive (\(-3 \times -3 = 9\)).

Definition Perfect Squares

A perfect square is an integer that is the square of another integer. The square root of a perfect square is an integer.

Example

The first few perfect squares are:$$ 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81, 100, \dots $$Their square roots are:$$ \sqrt{1} = 1, \quad \sqrt{4} = 2, \quad \sqrt{9} = 3, \quad \sqrt{16} = 4, \quad \dots $$

Definition Simplest Radical Form

A radical is written in simplest form if the number under the square root sign is as small as possible.

Calculating Square Roots

While the square roots of perfect squares are easy to find, most numbers are not perfect squares. We can estimate their square roots or use a calculator for a more precise value.

Method Use a calculator

On most calculators, you can find a square root using the \(\boxed{\sqrt{\;}}\) button.

Example

Use a calculator to find \(\sqrt{10}\), rounded to \(2\) decimal places.

Entering \(\sqrt{10}\) into a calculator gives approximately \(3.162277\ldots\)

Rounded to \(2\) decimal places, \(\sqrt{10} \approx 3.16\).

Rounded to \(2\) decimal places, \(\sqrt{10} \approx 3.16\).

Nth Roots

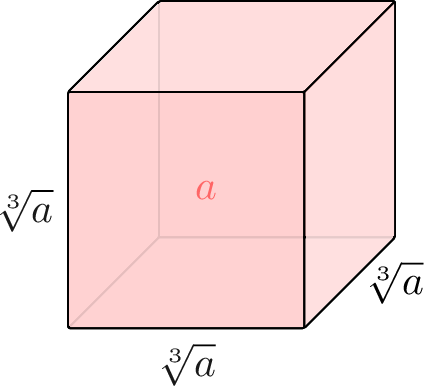

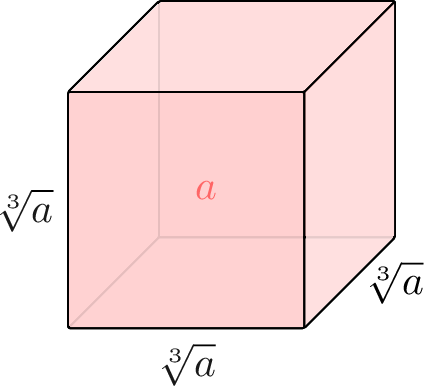

Just as the square root of a number is the side length of a square with a given area, the cube root \(\sqrt[3]{a}\) is the side length of a cube with volume \(a\).

Definition Cube Root

The cube root of a real number \(a\), written \(\sqrt[3]{a}\), is the (real) number which, when cubed, gives \(a\):$$\left(\sqrt[3]{a}\right)^3 = a$$

Note

Unlike square roots, cube roots are defined for all real numbers, including negatives. For example, \(\sqrt[3]{-27} = -3\) because \((-3) \times (-3) \times (-3) = -27\).

Example

Find \(\sqrt[3]{125}\).

\(\sqrt[3]{125} = 5\) because \(5 \times 5 \times 5 = 125\).

Definition Nth Root

The concept of a root can be generalized. For a positive integer \(n\), the nth root of a real number \(a\), written \(\sqrt[n]{a}\), is the number which, when raised to the power of \(n\), gives \(a\):$$\left(\sqrt[n]{a}\right)^n = a.$$The rules for their domains depend on whether the index \(n\) is even or odd.

- Even roots (e.g.\ \(\sqrt[2]{a}, \sqrt[4]{a}, \dots\)): an even root of a negative number is not a real number. For even \(n\), \(\sqrt[n]{a}\) is only defined for \(\boldsymbol{a \ge 0}\).

- Odd roots (e.g.\ \(\sqrt[3]{a}, \sqrt[5]{a}, \dots\)): an odd root is defined for all real numbers \(a\).

Laws of Radicals

Expressions involving square roots are called radical expressions (or simply radicals). To simplify and manipulate these expressions, we use a set of important laws.

Proposition Multiplication Law

For any real numbers \(a,b \ge 0\):$$\textcolor{colorprop} {\sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{b} = \sqrt{ab}} $$

By definition, squaring a square root gives the original number. Let's square the expression \(\sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{b}\):$$\begin{aligned}[t]\left(\sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{b}\right)^2 &= (\sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{b}) \times (\sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{b}) \\

&= (\sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{a}) \times (\sqrt{b} \times \sqrt{b}) \\

&= a \times b = ab\end{aligned}$$Since squaring \(\sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{b}\) gives \(ab\), then by definition, \(\sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{b}\) must be the square root of \(ab\).

Example

Show that \(\sqrt{4} \times \sqrt{9} = \sqrt{36}\).

$$\begin{aligned}[t]\sqrt{4} \times \sqrt{9} &= \sqrt{4\times 9} \\

&= \sqrt{36} \\

&= 6\end{aligned}$$

Proposition Square Root of a Square

For any real number \(a \ge 0\):$$ \textcolor{colorprop}{\sqrt{a^2} = a} $$

This follows directly from the multiplication law:$$\sqrt{a^2} = \sqrt{a \times a} = \sqrt{a} \times \sqrt{a} = (\sqrt{a})^2 = a$$

Example

Find \(\sqrt{25}\).

$$\begin{aligned}[t]\sqrt{25}& = \sqrt{5^2} \\

&= 5\end{aligned}$$

Proposition Simplifying Law

For any real numbers \(a,b \ge 0\):$$ \textcolor{colorprop}{\sqrt{a^2 b} = a\sqrt{b}} $$

$$\begin{aligned}[t]\sqrt{a^2 b} &= \sqrt{a^2} \times \sqrt{b} && \text{(by Multiplication Law)} \\

&= a \times \sqrt{b} && \text{(by Square Root of a Square Law)} \\

&= a\sqrt{b}\end{aligned}$$

Example

Simplify \(\sqrt{12}\).

First, find the largest perfect square factor of \(12\), which is \(4\).$$\begin{aligned}[t]\sqrt{12} &= \sqrt{4 \times 3} \\

&= \sqrt{2^2 \times 3} \\

&= 2\sqrt{3}\end{aligned}$$

Proposition Division Law

For any real numbers \(a \ge 0\) and \(b>0\):$$ \textcolor{colorprop}{\sqrt{\frac{a}{b}} = \frac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{b}}} $$

Let's square the expression \(\dfrac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{b}}\):$$\begin{aligned}[t]\left(\frac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{b}}\right)^2 &= \frac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{b}} \times \frac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{b}} \\

&= \frac{(\sqrt{a})^2}{(\sqrt{b})^2} \\

&= \frac{a}{b}\end{aligned}$$Since squaring \(\dfrac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{b}}\) gives \(\dfrac{a}{b}\), it must be the square root of \(\dfrac{a}{b}\).

Example

Simplify \(\sqrt{\dfrac{9}{16}}\).

$$\sqrt{\frac{9}{16}} = \frac{\sqrt{9}}{\sqrt{16}} = \frac{3}{4}$$

Algebraic Operations with Radicals

- We can only add or subtract radicals if they are like radicals, which means they have the exact same number under the root sign.

Think of it like algebra: you can simplify \(2x+4x\) to \(6x\), but you cannot simplify \(2x+4y\). In the same way, you can simplify \(2\sqrt{3} + 4\sqrt{3}\), but you cannot simplify \(2\sqrt{3} + 4\sqrt{5}\). - When multiplying expressions with radicals, we use the same rules as in algebra, such as the distributive law for expanding brackets, together with the radical laws we have just seen.

Method Algebraic Operations

We can perform operations with radicals (square roots) in a similar way to ordinary numbers, provided we respect the radical laws. In particular:

- We can add and subtract like radicals (i.e.\ the same number under the root) in the same way that we add and subtract like algebraic terms:$$ \textcolor{colorprop}{c\sqrt{a} + d\sqrt{a} = (c + d)\sqrt{a}} $$

- We can use the usual rules for expanding brackets (such as the distributive law).

Example

Simplify: \(2\sqrt{3} + 4\sqrt{3}\)

Just like \(2x+4x=6x\), we can add the coefficients of the like radical:$$2\sqrt{3} + 4\sqrt{3} = (2+4)\sqrt{3} = \boldsymbol{6\sqrt{3}}$$

Example

Expand and simplify \(\sqrt{3}(5 - \sqrt{3})\).$$ \begin{aligned}\sqrt{3}(5 - \sqrt{3}) &= (\sqrt{3} \times 5) - (\sqrt{3} \times \sqrt{3}) \\

&= 5\sqrt{3} - 3\end{aligned} $$

Rationalizing the Denominator

In mathematics, it is standard practice to write expressions without radicals in the denominator. The process of removing a radical from the denominator is called rationalizing the denominator. This does not change the value of the expression but converts it to a standard form which is often easier to work with.

Method Rationalizing a Monomial Denominator

To rationalize a denominator of the form \(\sqrt{a}\) (where \(a>0\)), multiply the numerator and the denominator by \(\sqrt{a}\).$$ \frac{b}{\sqrt{a}} = \frac{b}{\sqrt{a}} \times \frac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{a}} = \frac{b\sqrt{a}}{a} $$This works because multiplying by \(\frac{\sqrt{a}}{\sqrt{a}}\) is equivalent to multiplying by 1, which does not change the value.

Example

Rationalize the denominator of \(\frac{6}{\sqrt{2}}\).

We multiply the numerator and denominator by \(\sqrt{2}\).$$\begin{aligned}\frac{6}{\sqrt{2}} &= \frac{6}{\sqrt{2}} \times \frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}} \\

&= \frac{6\sqrt{2}}{2} \\

&= \boldsymbol{3\sqrt{2}}\end{aligned}$$

When the denominator is a binomial containing a square root, such as \(a+\sqrt{b}\), we use a special tool called the conjugate to rationalize it.

Definition Conjugate

The conjugate of a binomial expression \(x+y\) is \(x-y\).

Example

- The conjugate of \(a+\sqrt{b}\) is \(\boldsymbol{a-\sqrt{b}}\).

- The conjugate of \(a-\sqrt{b}\) is \(\boldsymbol{a+\sqrt{b}}\).

The power of the conjugate lies in its product, which follows the difference of squares identity: \((x+y)(x-y) = x^2 - y^2\).$$ (a+\sqrt{b})(a-\sqrt{b}) = a^2 - (\sqrt{b})^2 = a^2 - b $$The result is a rational number, which achieves our goal.

Method Rationalizing a Binomial Denominator

To rationalize a binomial denominator, multiply the numerator and the denominator by the conjugate of the denominator.

Example

Rationalize the denominator of \(\frac{4}{3+\sqrt{5}}\).

The denominator is \(3+\sqrt{5}\). Its conjugate is \(3-\sqrt{5}\). We multiply the numerator and denominator by this conjugate.$$\begin{aligned}\frac{4}{3+\sqrt{5}} &= \frac{4}{(3+\sqrt{5})} \times \frac{(3-\sqrt{5})}{(3-\sqrt{5})} \\

&= \frac{4(3 - \sqrt{5})}{3^2 - (\sqrt{5})^2} &&\color{gray}{\text{(Using }(x+y)(x-y)=x^2-y^2)}\\

&= \frac{12 - 4\sqrt{5}}{9 - 5} \\

&= \frac{12 - 4\sqrt{5}}{4} \\

&= \frac{4(3 - \sqrt{5})}{4} &&\color{gray}{\text{(Factor out 4 to simplify)}} \\

&= \boldsymbol{3 - \sqrt{5}}\end{aligned}$$