Complex Numbers: Geometrical Approach

While the algebraic approach provides the rules for manipulating complex numbers, the geometrical approach offers a powerful and intuitive way to understand their meaning. By representing complex numbers as points or vectors in a plane, we can visualise their operations as geometric transformations such as rotations, reflections, and scalings. This chapter explores the geometry of the complex plane, providing insight into the concepts of modulus, argument, and the geometric patterns formed by the roots of complex numbers.

Complex Plane

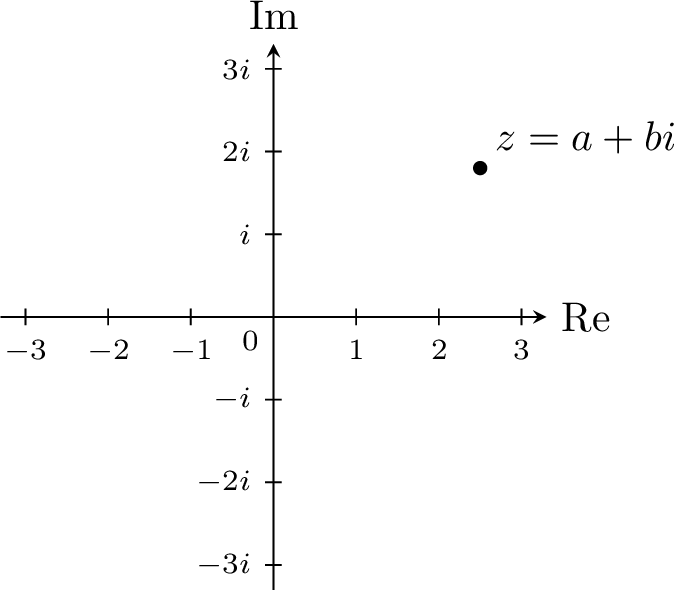

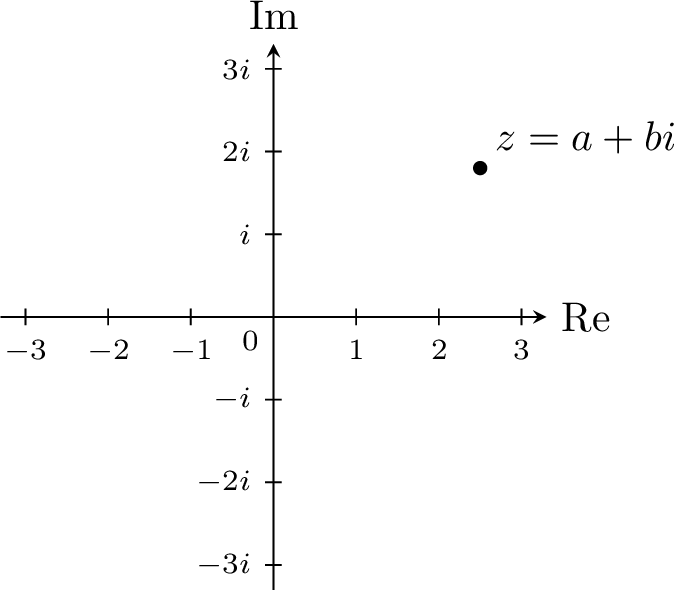

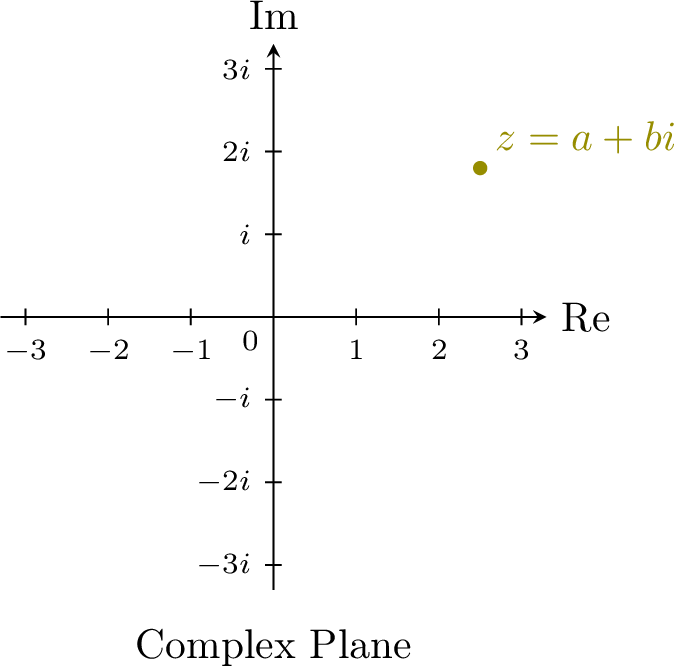

We have seen that a complex number can be written in Cartesian (algebraic) form as \(z = a+bi\) where \(a = \Re(z)\) and \(b = \Im(z)\) are both real numbers.

There is a one-to-one correspondence between any complex number \(a+bi\) and the point \((a, b)\).

We can therefore plot any complex number on a plane by associating it with a unique point, giving a geometric representation to what was previously an algebraic object. We refer to this plane as the complex plane.

There is a one-to-one correspondence between any complex number \(a+bi\) and the point \((a, b)\).

We can therefore plot any complex number on a plane by associating it with a unique point, giving a geometric representation to what was previously an algebraic object. We refer to this plane as the complex plane.

Definition Complex Plane

The complex plane is the plane formed by the complex numbers, endowed with a Cartesian coordinate system such that:

- the horizontal \(x\)-axis, called the real axis, consists of the real numbers

- the vertical \(y\)-axis, called the imaginary axis, consists of the purely imaginary numbers.

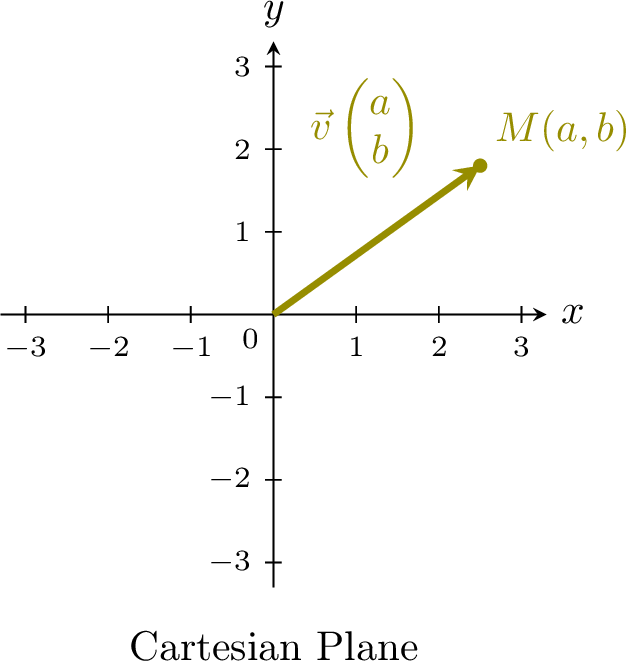

Definition Relationship between Cartesian and Complex Representations

- The point \(M(a, b)\) is the point corresponding to the complex number \(z=a+bi\).

- The vector \(\vec{v} = \begin{pmatrix} a \\ b \end{pmatrix}\) is the position vector representing the complex number \(z=a+bi\).

- The complex number \(z=a+bi\) is the affix of the point \(M(a, b)\) and of the vector \(\vec{v} = \begin{pmatrix} a \\ b \end{pmatrix}\).

Modulus and Argument

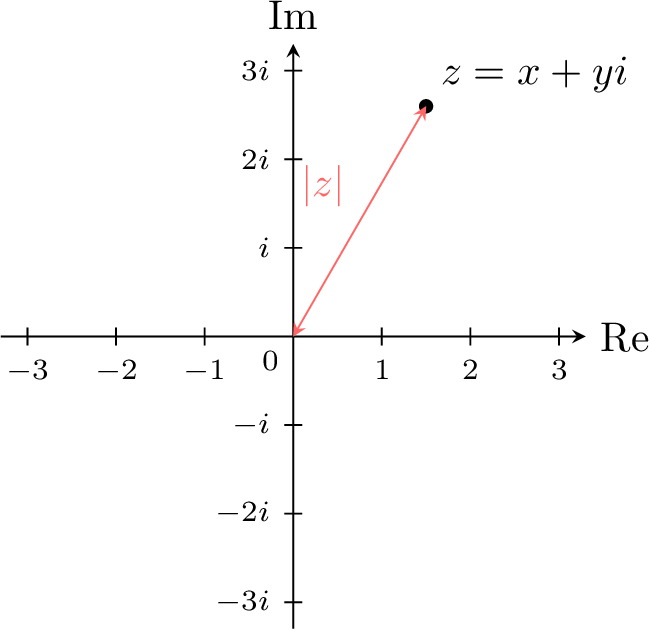

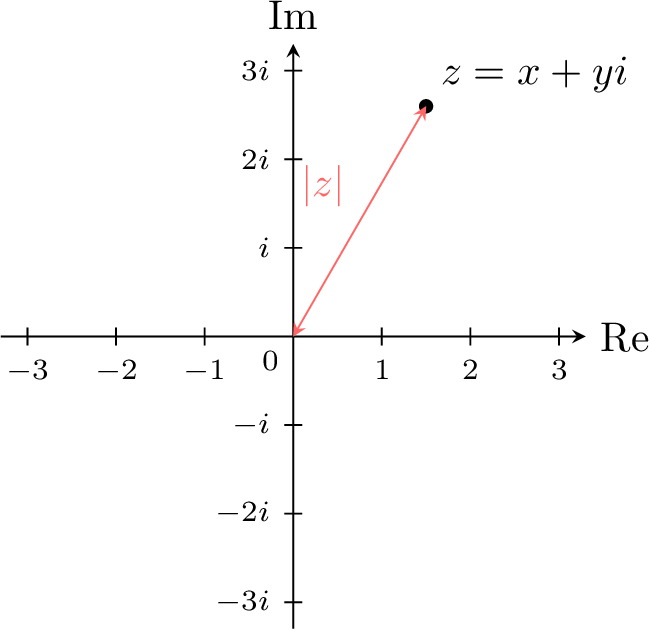

Geometrically, every complex number has two key characteristics: its distance from the origin and its direction relative to the positive real axis.

Definition Modulus

The modulus of a complex number \(z = x+yi\), denoted \(|z|\), is the distance from the origin to its corresponding point in the complex plane. By the Pythagorean theorem, it is defined as:$$|z| = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}.$$The modulus is a non-negative real number.

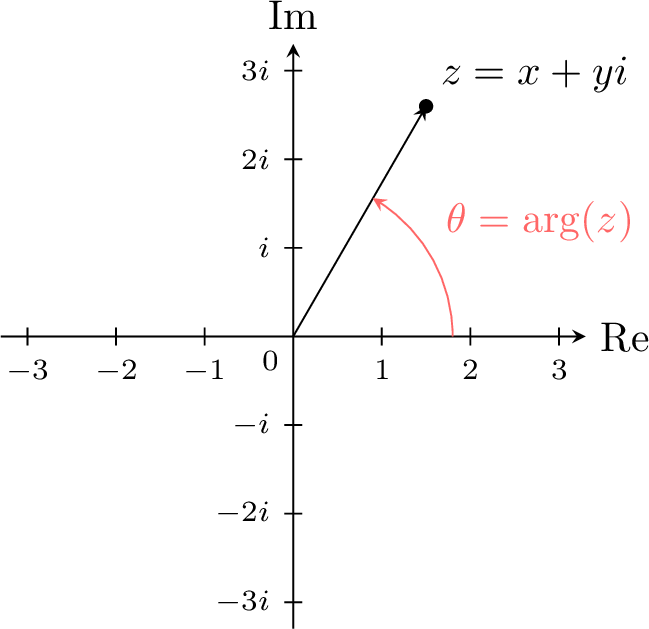

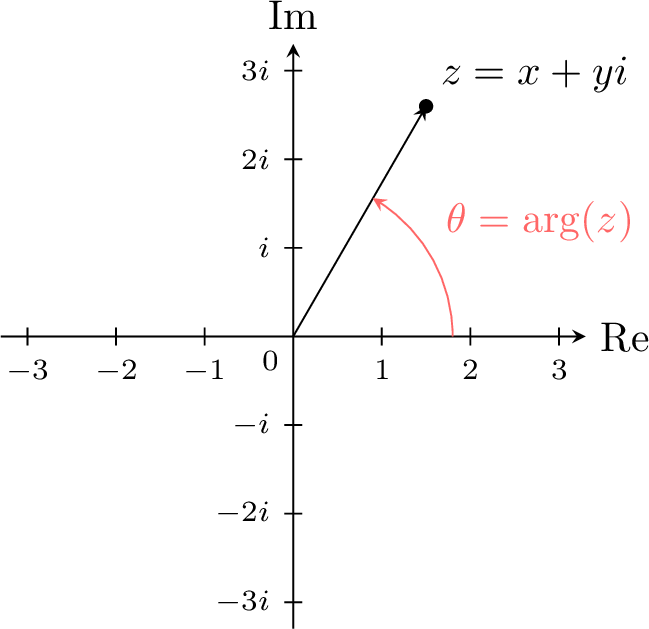

Definition Argument

The argument of a non-zero complex number \(z\), denoted \(\arg(z)\), is any real number \(\theta\) such that \(\theta\) is the angle measured anti-clockwise between the positive real axis and the vector representing \(z\).

Note

An argument of a complex number is not unique, as any multiple of \(2\pi\) can be added to the angle. To make it unique, we define the principal value of the argument as the value of \(\theta\) in the interval \((-\pi, \pi]\).

The argument of \(0\) is undefined.

The argument of \(0\) is undefined.

Example

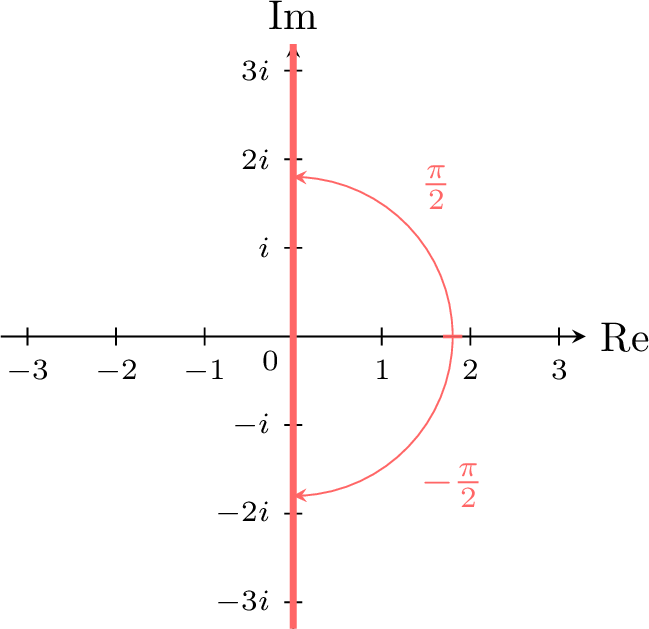

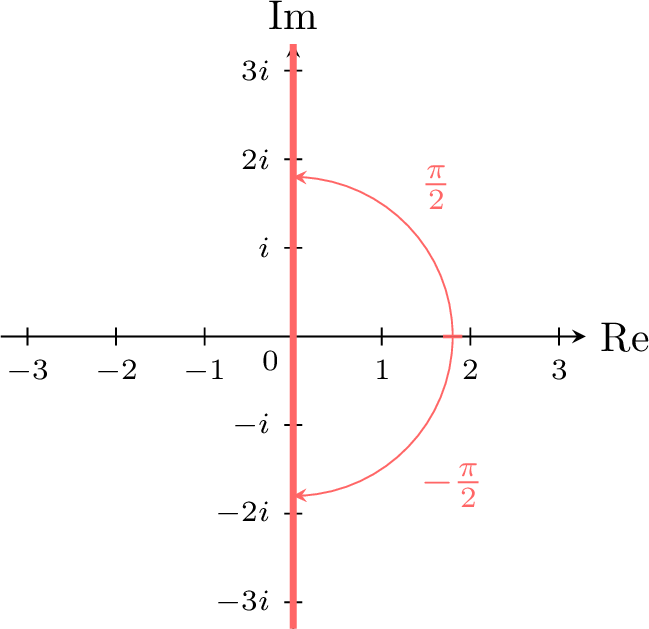

Non-zero purely imaginary numbers have an argument of \(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\) or \(-\dfrac{\pi}{2}\).

Method Calculating the Argument

To find an argument \(\theta\) of a non-zero complex number \(z=a+bi\):

- Calculate the modulus \(|z| = \sqrt{a^2+b^2}\).

- Factor out the modulus to identify the coordinates of the corresponding point on the unit circle: $$ z = |z| \left( \frac{a}{|z|} + i \frac{b}{|z|} \right). $$

- Identify the angle. Find an angle \(\theta\) that satisfies the system of equations: $$ \begin{cases} \cos(\theta) = \dfrac{a}{|z|} \\ \sin(\theta) = \dfrac{b}{|z|} \end{cases} $$ This value of \(\theta\) is an argument of \(z\).

Example

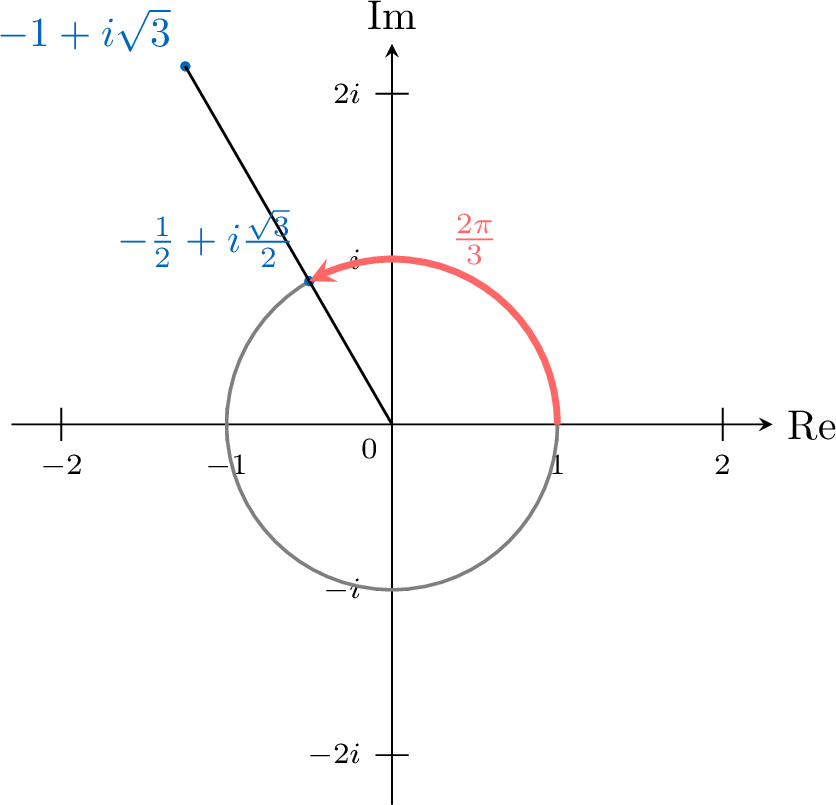

Find an argument of the complex number \(z = -1+i\sqrt{3}\).

- We first calculate the modulus of \(z\): $$|z| = \sqrt{(-1)^2 + (\sqrt{3})^2} = \sqrt{1+3} = 2.$$ We can then factor out the modulus: $$ z = 2 \times \left(-\frac{1}{2} + i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right). $$

- We are looking for a real number \(\theta\) such that: $$ \begin{cases} \cos(\theta) = -\dfrac{1}{2} \\

\sin(\theta) = \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2} \end{cases} $$ The angle \(\theta = \dfrac{2\pi}{3}\) satisfies both equations.

Therefore, an argument of \(z\) is \(\dfrac{2\pi}{3}\).

Unit Modulus Complex Numbers and the Imaginary Exponential

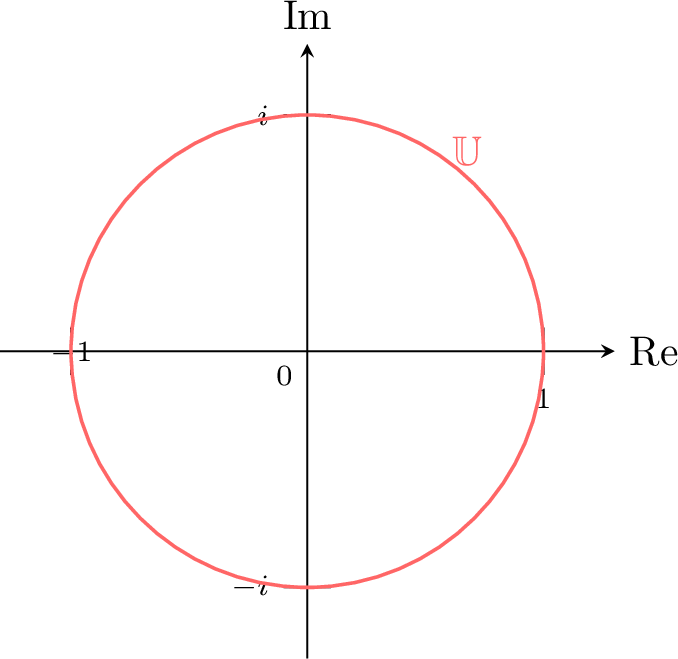

Definition Unit Circle in the Complex Plane

The set of all complex numbers with modulus \(1\) is called the unit circle, denoted \(\mathbb{U}\):$$\mathbb{U}=\{z \in \mathbb{C} \mid |z |=1\}.$$

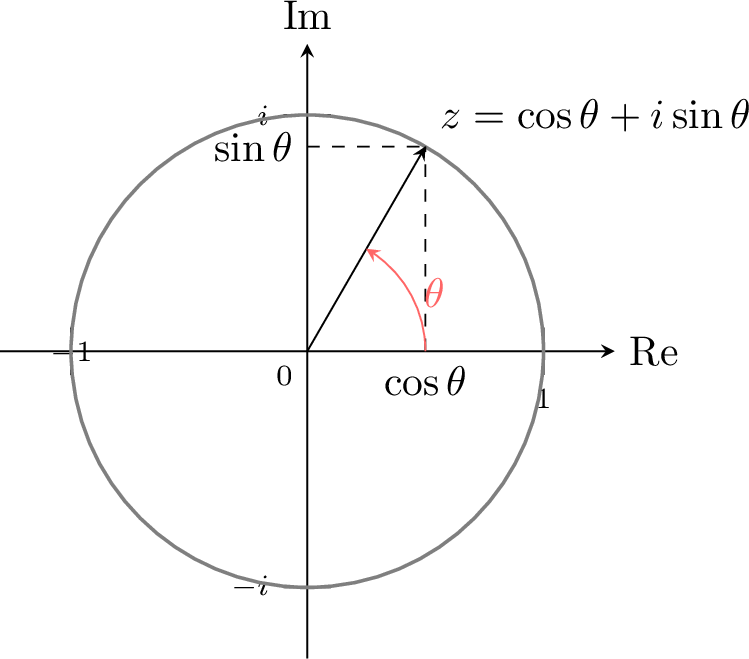

Proposition Trigonometric Form of Unit Modulus Numbers

If \(z \in \mathbb{U}\), then there exists a real number \(\theta\) such that$$z=\cos\theta+i\sin\theta.$$Here, \(\theta\) is an argument of \(z\).

Motivation for Euler's Notation

Let \(f\) be the function defined on \(\mathbb{R}\) by$$f(\theta) = \cos(\theta) + i \sin(\theta).$$Using the angle addition formulas, one can show that, for all real numbers \(\theta_1\) and \(\theta_2\),$$ f(\theta_1 + \theta_2) = f(\theta_1)\, f(\theta_2). $$This is the same fundamental property as the real exponential function (\(e^{x+y}=e^x e^y\)). This strong analogy motivates the notation$$f(\theta) = e^{i\theta}.$$

Definition Imaginary Exponential

For any real number \(\theta\), we define the imaginary exponential, denoted \(e^{i\theta}\), as the complex number$$e^{i\theta} = \cos \theta + i \sin \theta.$$

Proposition Properties of the Imaginary Exponential

For any real numbers \(\theta\) and \(\theta'\), and for any integer \(n\), the imaginary exponential has the following properties:

- Modulus: \(|e^{i\theta}| = 1\)

- Argument: \(\arg(e^{i\theta}) \equiv \theta \pmod{2\pi}\)

- Conjugate: \(\conjugate{e^{i\theta}} = e^{-i\theta}\)

- Product Rule: \(e^{i(\theta+\theta')} = e^{i\theta}\, e^{i\theta'}\)

- Power Rule: \((e^{i\theta})^n = e^{in\theta}\)

Polar and Euler's Forms

Any non-zero complex number can be represented by starting with a number on the unit circle and scaling it by its modulus.

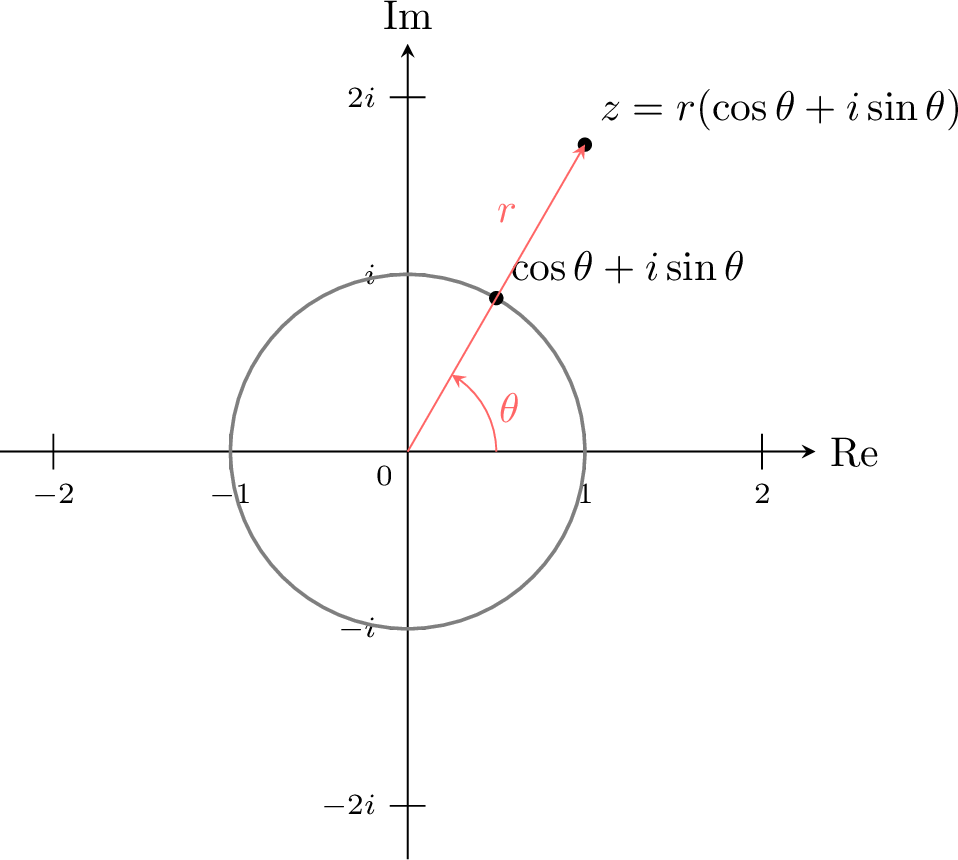

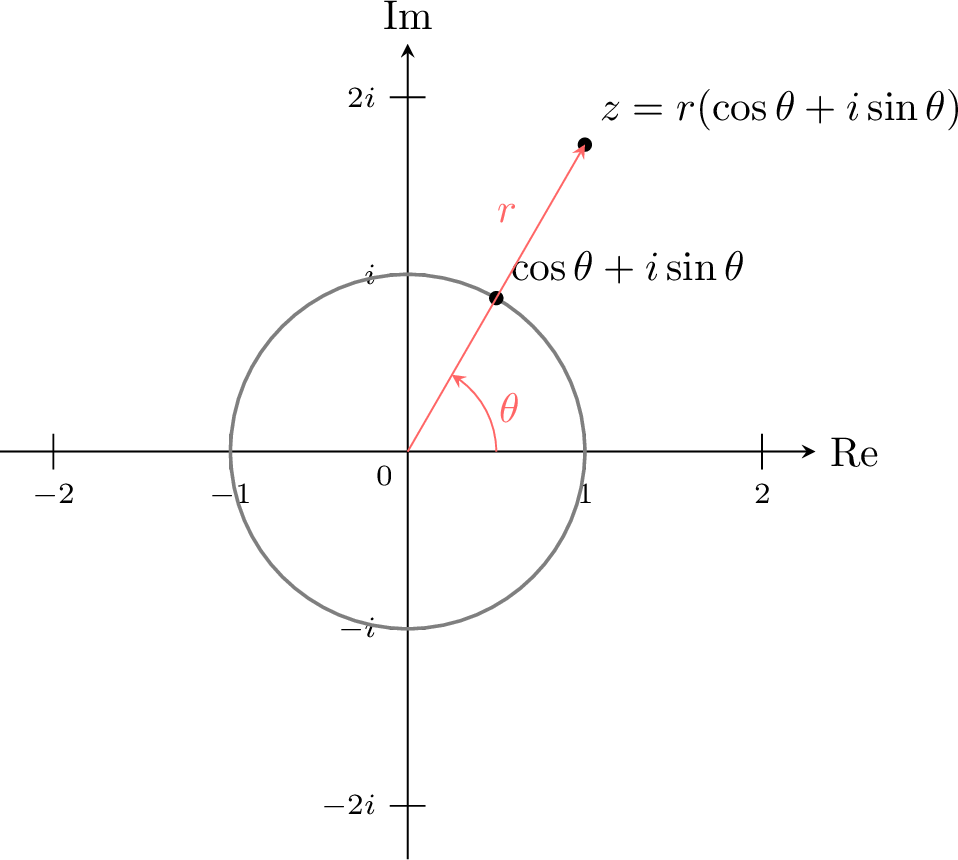

Definition Polar Form

A non-zero complex number \(z\) with modulus \(r = |z|\) and an argument \(\theta \in \arg(z)\) can be written in polar form as$$ z = r(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta). $$

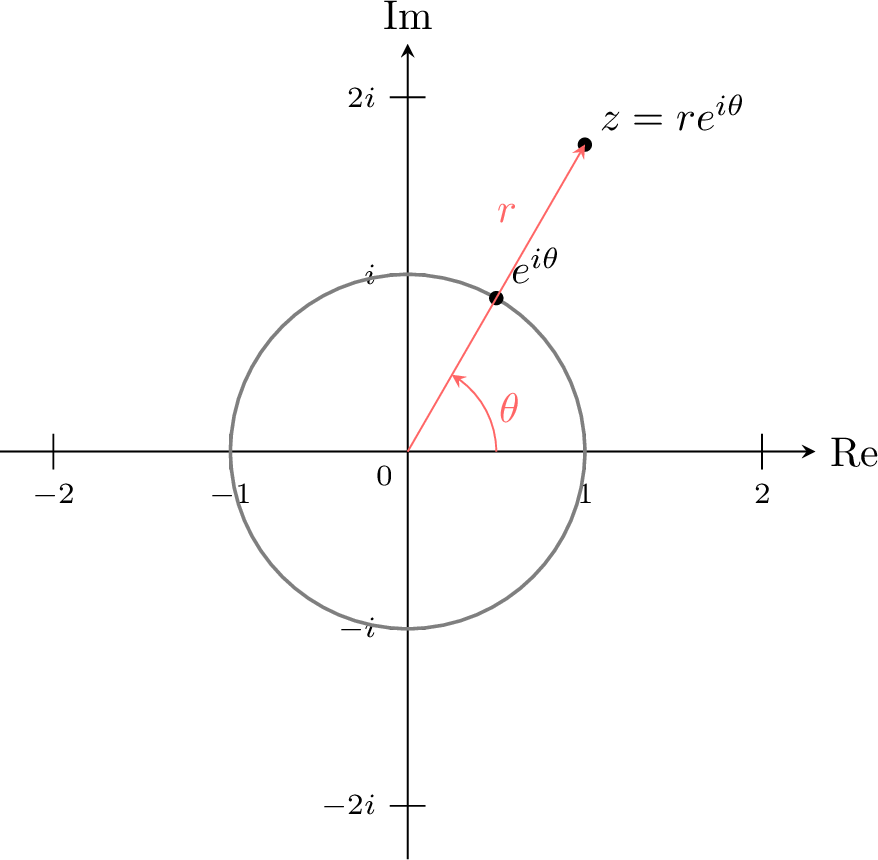

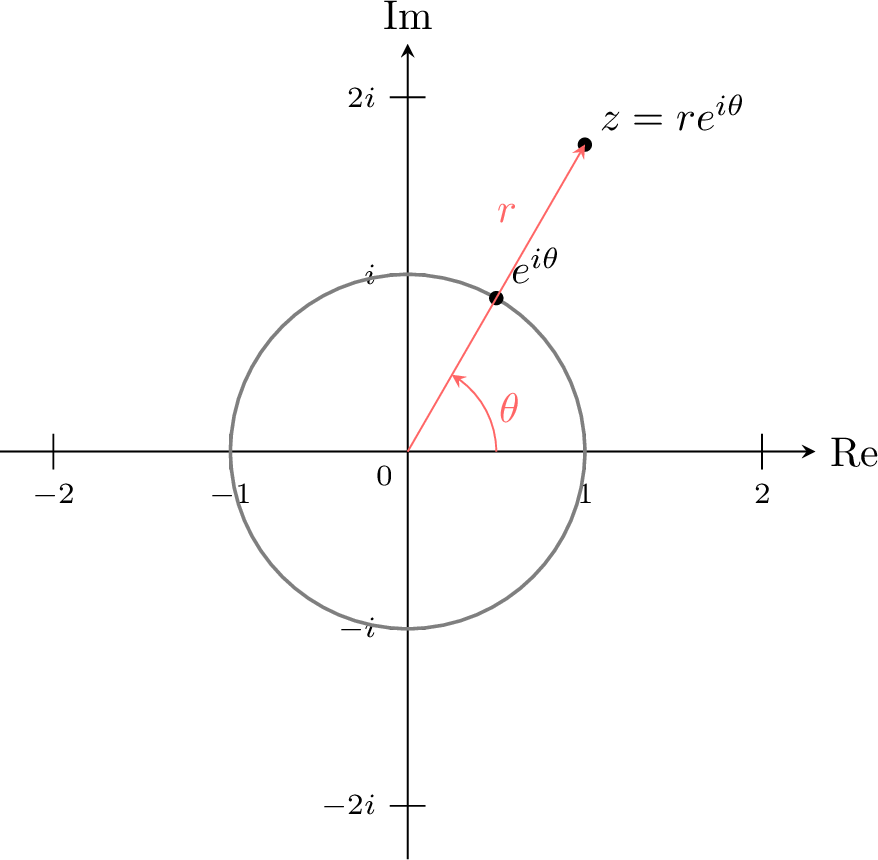

Definition Euler's Form

Using the imaginary exponential, a non-zero complex number \(z\) with modulus \(r = |z|\) and an argument \(\theta \in \arg(z)\) can be written in Euler's form as$$ z = re^{i\theta}. $$

Note

This form makes the geometric rules of multiplication intuitive:$$(r_1 e^{i\theta_1})(r_2 e^{i\theta_2}) = (r_1r_2)e^{i(\theta_1+\theta_2)}.$$Multiplying complex numbers corresponds to multiplying their moduli and adding their arguments.

De Moivre's Theorem

Proposition De Moivre's Theorem

For any complex number \(z = r(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta)\) and for any integer \(n\):$$ [r(\cos\theta + i\sin\theta)]^n = r^n(\cos(n\theta) + i\sin(n\theta)). $$In Euler's form, this is expressed concisely as:$$ (re^{i\theta})^n = r^n e^{in\theta}. $$

The most direct proof uses Euler's form, which extends the familiar laws of exponents to complex numbers.

Let \(z = re^{i\theta}\). Raising this to the power \(n\) gives$$\begin{aligned} z^n &= (re^{i\theta})^n \\ &= r^n \left(e^{i\theta}\right)^n \quad &&\text{(power of a product rule)} \\ &= r^n e^{i(n\theta)} \quad &&\text{(power of a power rule)}.\end{aligned}$$Converting this result back to polar (trigonometric) form gives:$$ z^n = r^n (\cos(n\theta) + i\sin(n\theta)). $$This proves the theorem for any integer \(n\).

Let \(z = re^{i\theta}\). Raising this to the power \(n\) gives$$\begin{aligned} z^n &= (re^{i\theta})^n \\ &= r^n \left(e^{i\theta}\right)^n \quad &&\text{(power of a product rule)} \\ &= r^n e^{i(n\theta)} \quad &&\text{(power of a power rule)}.\end{aligned}$$Converting this result back to polar (trigonometric) form gives:$$ z^n = r^n (\cos(n\theta) + i\sin(n\theta)). $$This proves the theorem for any integer \(n\).

Example Calculating a Power using Euler's Form

Calculate \((1+\sqrt{3}i)^5\).

- Step 1: Convert to Euler's form.

\(\begin{aligned}[t] r &= |1+\sqrt{3}i| \\ &= \sqrt{1^2 + (\sqrt{3})^2} \\ &= \sqrt{4} \\ &= 2 \end{aligned} \qquad\text{and}\qquad \begin{aligned}[t] \theta &= \arg(1+\sqrt{3}i) \\ &= \arctan\left(\frac{\sqrt{3}}{1}\right) \\ &= \frac{\pi}{3}. \end{aligned}\)

So, \(1+\sqrt{3}i = 2e^{i\frac{\pi}{3}}\). - Step 2: Apply De Moivre's Theorem and convert back.

Using De Moivre's theorem and the identity \(e^{i\varphi} = \cos\varphi+i\sin\varphi\):$$\begin{aligned}(1+\sqrt{3}i)^5 &= \left(2e^{i\frac{\pi}{3}}\right)^5 \\ &= 2^5 e^{i\frac{5\pi}{3}} \\ &= 32\left(\cos\left(\frac{5\pi}{3}\right) + i\sin\left(\frac{5\pi}{3}\right)\right) \\ &= 32\left(\frac{1}{2} - i\frac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) \\ &= 16 - 16\sqrt{3}i.\end{aligned}$$

Properties of Modulus and Argument

Proposition Properties of the Modulus

- \(|\conjugate{z}| = |z|\)

- \(|z|^2 = z\conjugate{z}\)

- \(|z_1 z_2| = |z_1|\, |z_2|\)

- \(\left| \dfrac{z_1}{z_2} \right| = \dfrac{|z_1|}{|z_2|}\) provided \(z_2 \neq 0\)

- \(|z^n| = |z|^n\) for any integer \(n\).

These properties can be rigorously proven using the algebraic definition of the modulus. The proofs are left as exercises.

Proposition Properties of Arguments

For any non-zero complex numbers \(z_1\) and \(z_2\) and any integer \(n\):

- for any non-zero complex number \(z\), \(\arg(\conjugate{z}) \equiv -\arg(z) \pmod{2\pi}\)

- \(\arg(z_1 z_2) \equiv \arg(z_1) + \arg(z_2) \pmod{2\pi}\)

- \(\arg\left(\dfrac{z_1}{z_2}\right) \equiv \arg(z_1) - \arg(z_2) \pmod{2\pi}\)

- \(\arg(z^n) \equiv n \arg(z) \pmod{2\pi}\) for any non-zero complex number \(z\).

These properties are most easily proven using Euler's form. The proofs are left as exercises.

Geometry in the Coordinate Plane

Proposition Addition and Subtraction

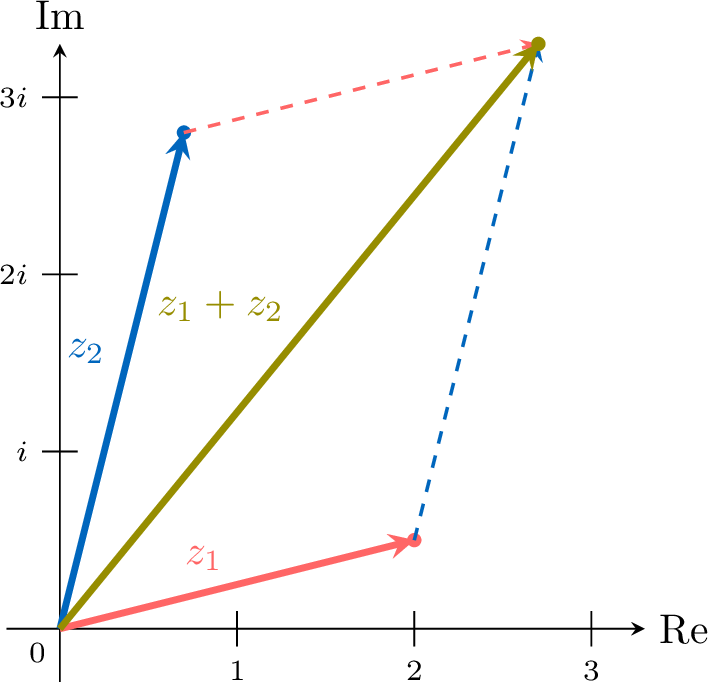

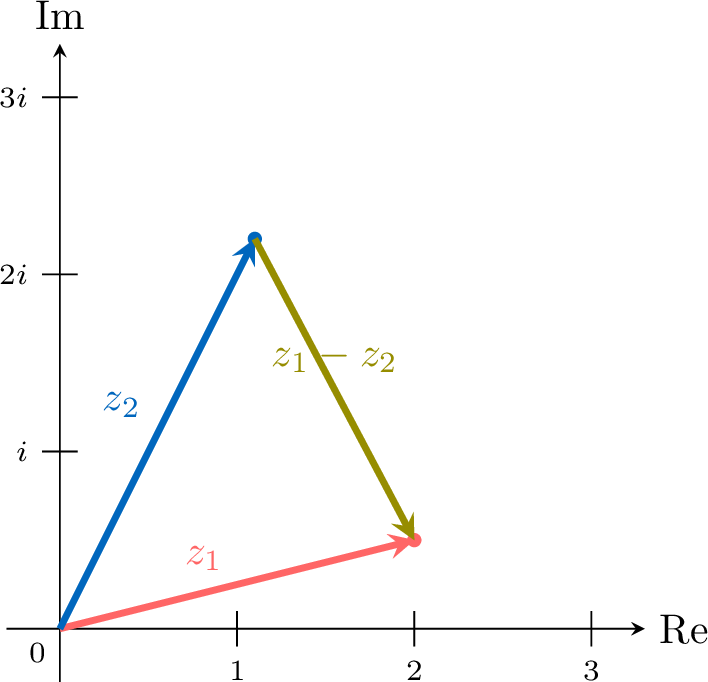

Adding or subtracting complex numbers is equivalent to the vector addition or subtraction of their corresponding position vectors, following the parallelogram law.

- Addition (\(z_1+z_2\)): The vector for the sum is the main diagonal of the parallelogram formed by the vectors for \(z_1\) and \(z_2\).

- Subtraction (\(z_1-z_2\)): The vector for the difference is the vector from the point representing \(z_2\) to the point representing \(z_1\).

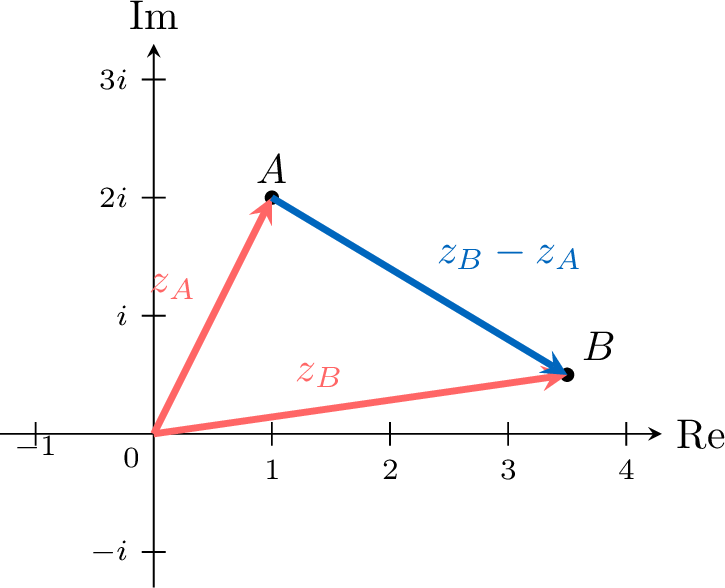

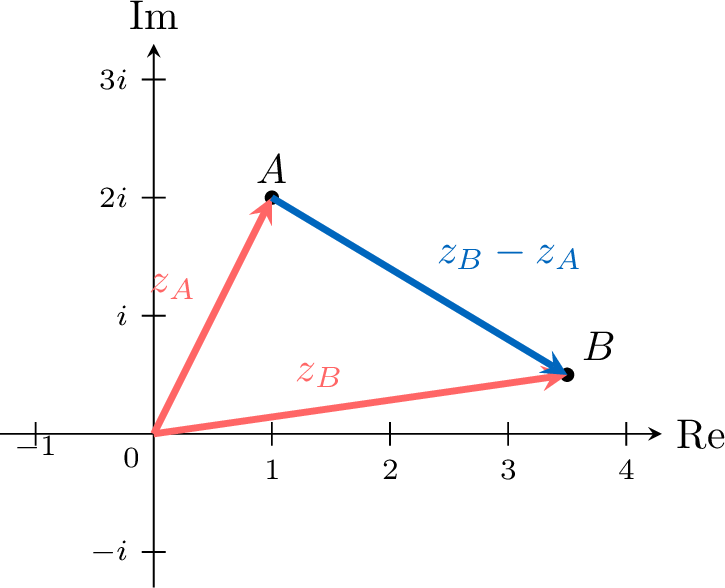

Proposition Affix of a Vector and Distance between Points

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two points in the complex plane with respective affixes \(z_A\) and \(z_B\).

- The vector \(\Vect{AB}\) has the affix \(z_{\Vect{AB}} = z_B - z_A\).

- The distance between points \(A\) and \(B\) is the modulus of this affix: $$ AB = |z_B - z_A|. $$

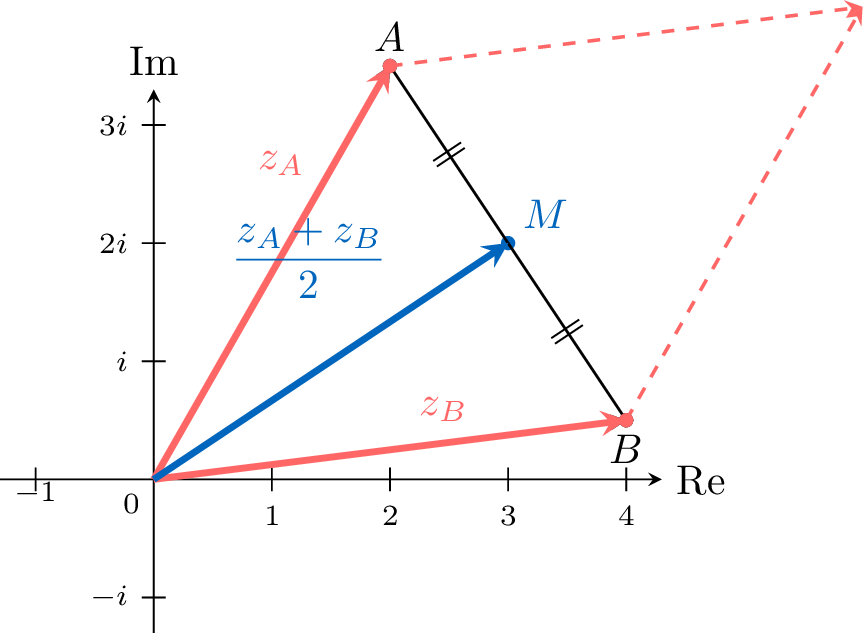

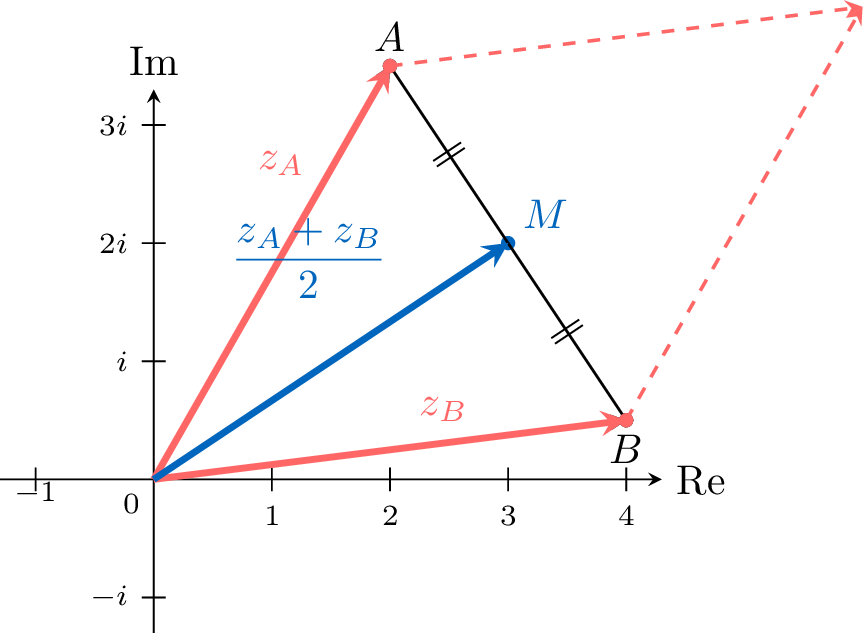

Proposition Affix of a Midpoint

Let \(A\) and \(B\) be two points in the complex plane with affixes \(z_A\) and \(z_B\).

The midpoint \(M\) of the segment \(\SegmentFr{AB}\) has the affix$$ z_M = \frac{z_A + z_B}{2}. $$

The midpoint \(M\) of the segment \(\SegmentFr{AB}\) has the affix$$ z_M = \frac{z_A + z_B}{2}. $$

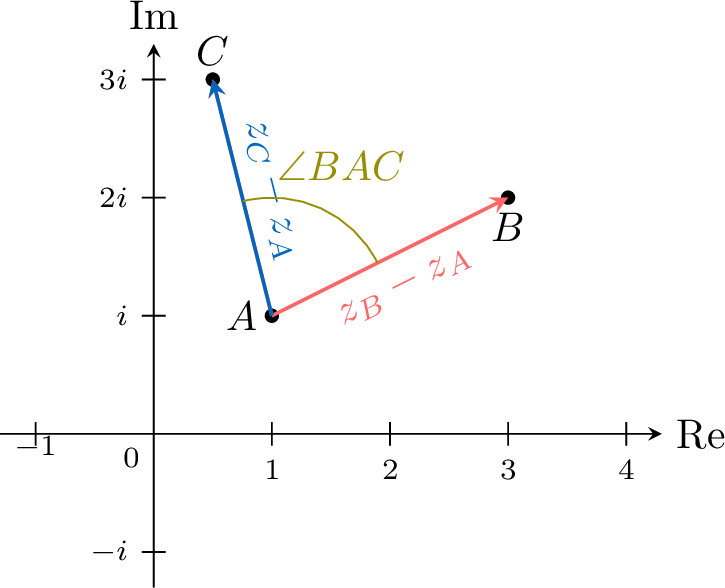

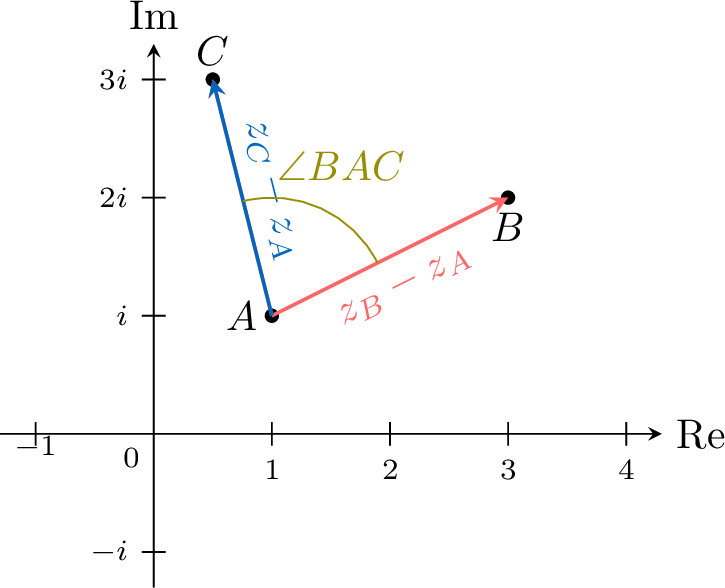

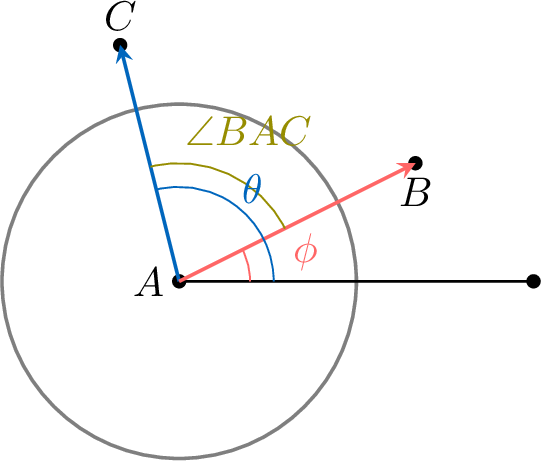

Proposition Angle

Let \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\) be three distinct points in the complex plane with respective affixes \(z_A\), \(z_B\), and \(z_C\). The measure of the angle \(\Angle{BAC}\) is given by$$ \Angle{BAC} = \arg\left(\frac{z_C-z_A}{z_B-z_A}\right). $$

The measure of the angle \(\Angle{BAC}\) is the difference between the angle of the vector \(\Vect{AC}\) and the angle of the vector \(\Vect{AB}\), both measured from the positive real axis.

- The affix of \(\Vect{AC}\) is \(z_C-z_A\), so \(\theta = \arg(z_C-z_A)\).

- The affix of \(\Vect{AB}\) is \(z_B-z_A\), so \(\phi = \arg(z_B-z_A)\).

Proposition Multiplication and Division

Multiplying or dividing complex numbers corresponds to scaling their moduli and rotating their arguments.

- Multiplication (\(z_1 z_2\)): Multiply the moduli and add the arguments.

- Division (\(\dfrac{z_1}{z_2}\)): Divide the moduli and subtract the arguments.

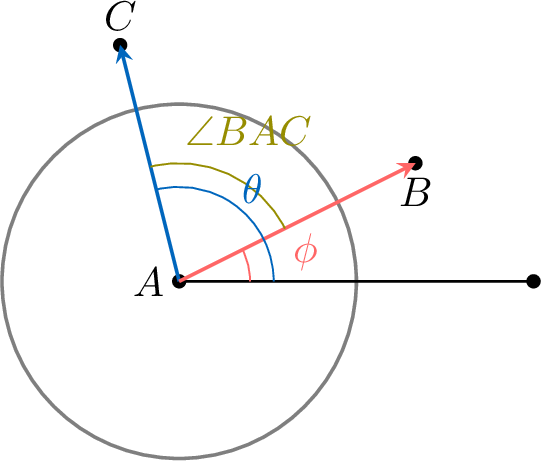

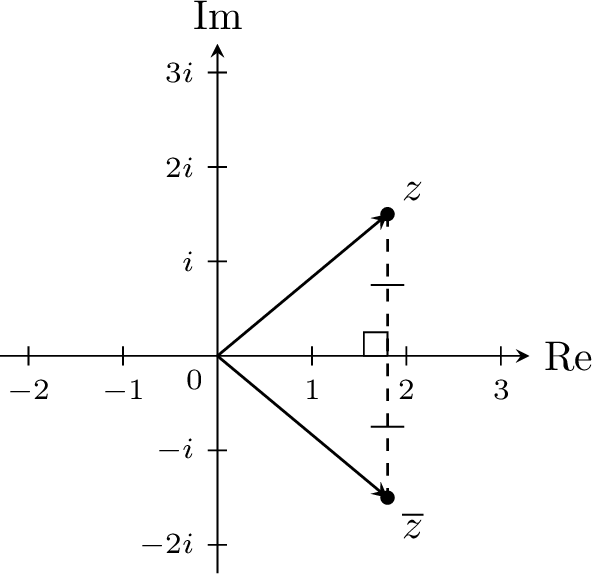

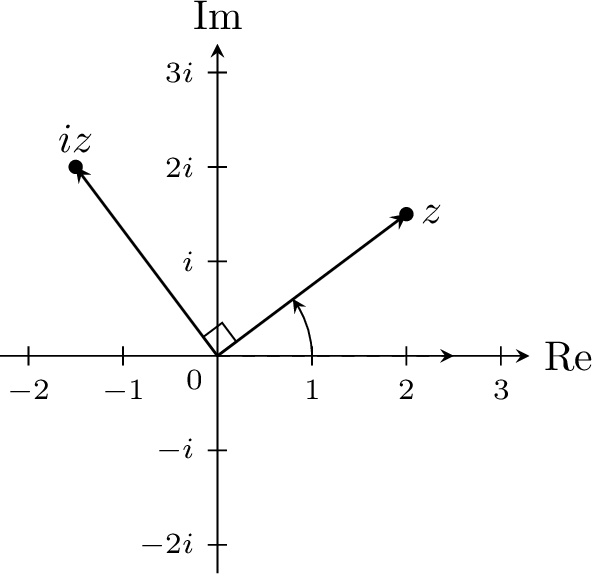

Proposition Fundamental Geometric Transformations

- Conjugate (\(z \to \conjugate{z}\)): a reflection across the real axis.

- Negation (\(z \to -z\)): a rotation of \(180^\circ\) (or \(\pi\) radians) about the origin.

- Multiplication by \(i\) (\(z \to iz\)): a rotation of \(90^\circ\) (or \(\pi/2\) radians) anti-clockwise about the origin.

Geometric Loci in the Complex Plane

Equations and inequalities involving complex numbers can define geometric shapes or regions, known as loci, in the complex plane. Understanding the geometric meaning of modulus and argument is key to interpreting these loci.

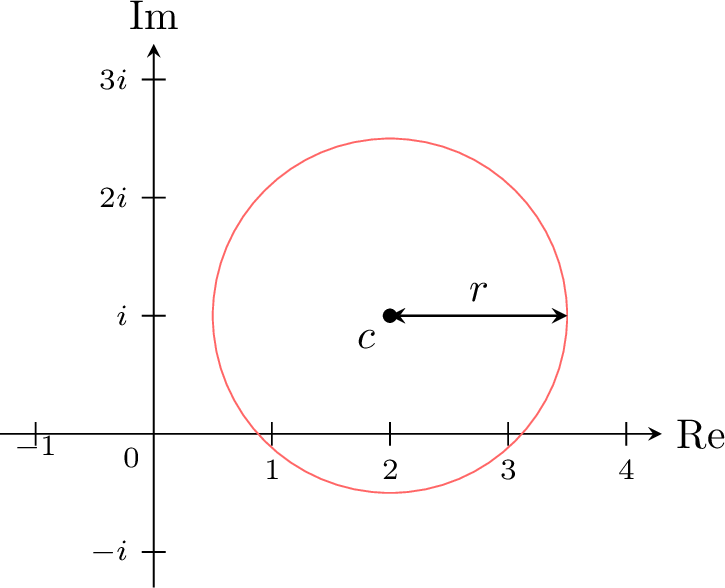

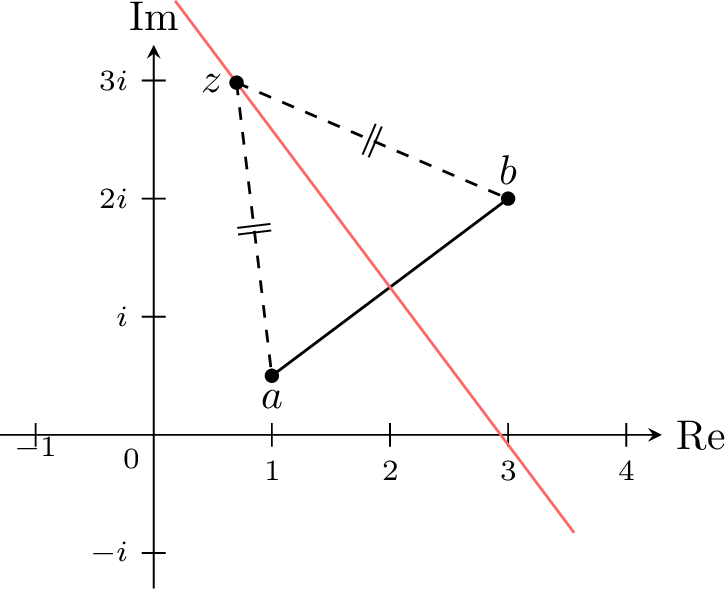

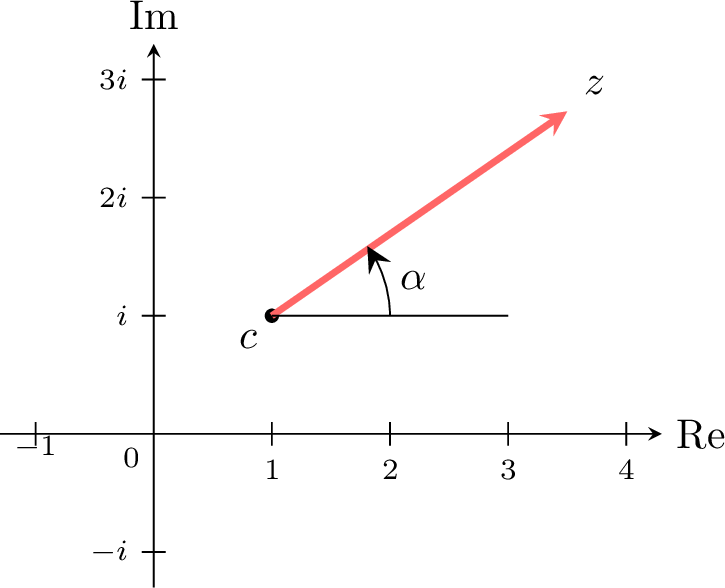

Proposition Fundamental Geometric Loci

- Circles: The equation \(|z-c| = r\) describes a circle with centre \(c\) and radius \(r\). This is the set of all points \(z\) that are at a fixed distance \(r\) from the point \(c\).

- Perpendicular Bisectors: The equation \(|z-a| = |z-b|\) describes the perpendicular bisector of the line segment connecting points \(a\) and \(b\). This is the set of all points \(z\) that are equidistant from \(a\) and \(b\).

- Rays: The equation \(\arg(z-c) = \alpha\) describes a ray originating from the point \(c\) (but not including \(c\)) at a fixed angle \(\alpha\) to the positive real direction.

Roots of Complex Numbers

Just as De Moivre's theorem provides a powerful method for raising complex numbers to a power, it also gives us a systematic way to find the \(n\)-th roots of any complex number. We begin with the special case of finding the roots of \(1\).

Definition Roots of Unity

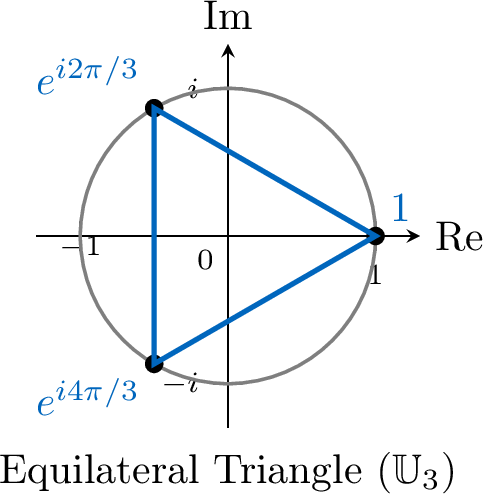

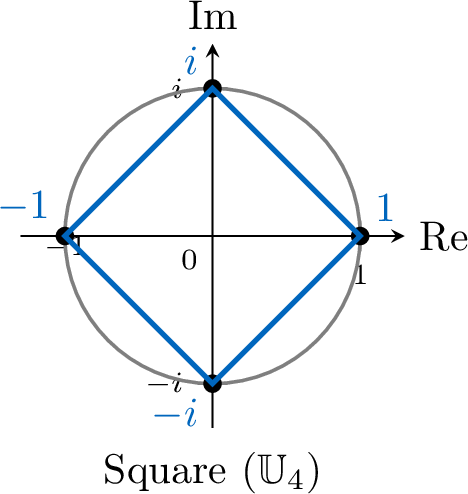

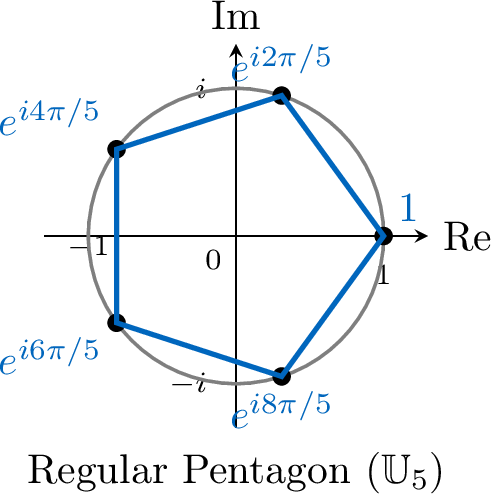

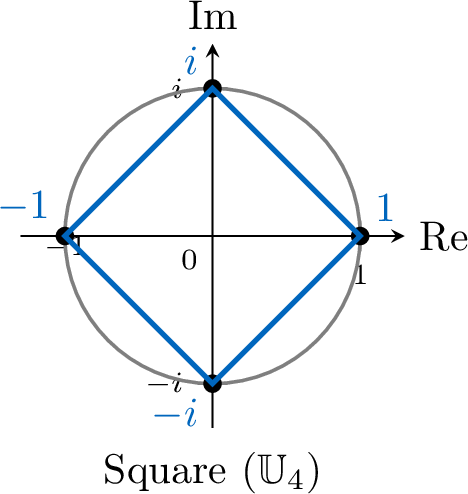

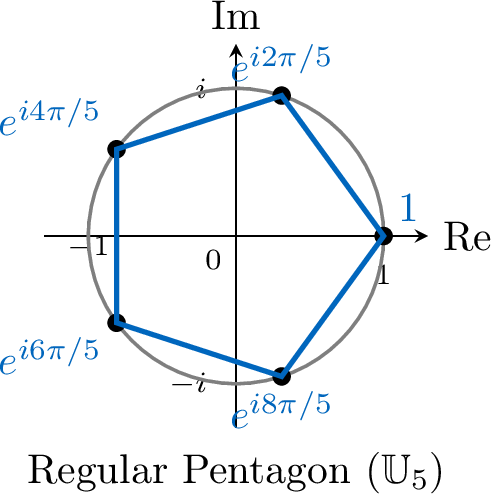

For any integer \(n \ge 1\), an \(n\)-th root of unity is any complex number \(z\) such that \(z^n = 1\). The set of all \(n\)-th roots of unity is denoted by \(\mathbb{U}_n\).

Proposition Structure of the Set of Roots of Unity

For any integer \(n \ge 1\), the set of the \(n\)-th roots of unity is$$\mathbb{U}_n = \left\{ e^{i\frac{2k\pi}{n}} \;|\; k=0, 1, 2, \dots, n-1 \right\}.$$Geometrically, the points representing the \(n\)-th roots of unity form the vertices of a regular \(n\)-sided polygon inscribed in the unit circle, with one vertex at the point \(1\).

Proposition Finding n-th Roots

A non-zero complex number \(c = \rho e^{i\alpha}\) has exactly \(n\) distinct \(n\)-th roots. The roots are the solutions to the equation \(z^n = c\), given by the formula$$ z_k = \rho^{\frac{1}{n}} e^{i\left(\frac{\alpha + 2k\pi}{n}\right)} \quad \text{for } k = 0, 1, 2, \dots, n-1. $$Geometrically, the roots form the vertices of a regular \(n\)-sided polygon inscribed in a circle of radius \(\rho^{1/n}\).

We want to solve \(z^n = c\) for \(z\). Let \(z = re^{i\theta}\) and \(c=\rho e^{i\alpha}\):$$\begin{aligned} (re^{i\theta})^n &= \rho e^{i\alpha} \\

r^n e^{in\theta} &= \rho e^{i\alpha}.\end{aligned}$$For two complex numbers to be equal, their moduli must be equal and their arguments must be coterminal (that is, differ by a multiple of \(2\pi\)).

- Equating moduli: \(r^n = \rho \implies r = \rho^{1/n}\) (since \(r\) is a positive real).

- Equating arguments: \(n\theta = \alpha + 2k\pi \implies \theta = \dfrac{\alpha + 2k\pi}{n}\) for \(k \in \mathbb{Z}\).

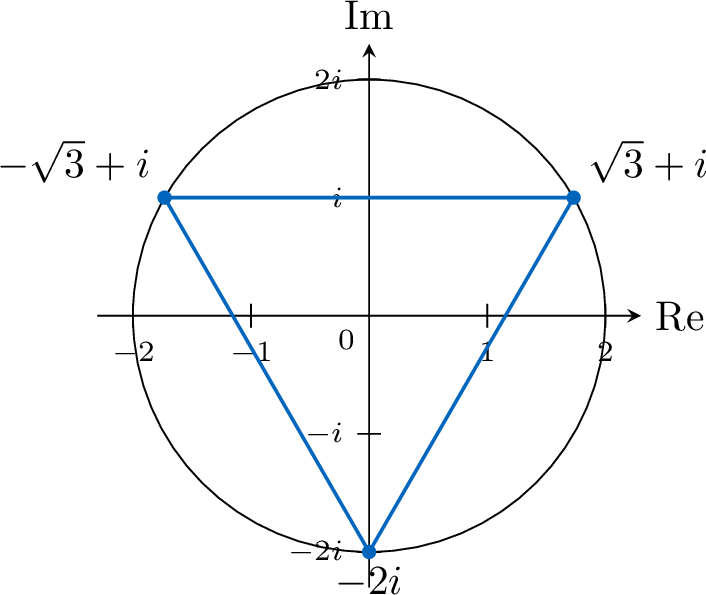

Example

Find the three cube roots of \(c = 8i\).

- Step 1: Convert to Euler form.

\(\rho = |8i| = 8\). \(\alpha = \arg(8i) = \frac{\pi}{2}\). So, \(c = 8e^{i\frac{\pi}{2}}\). - Step 2: Apply the root formula.

The modulus of the roots is \(r = 8^{1/3} = 2\).

The arguments are \(\phi_k = \frac{\pi/2 + 2k\pi}{3}\) for \(k=0,1,2\). - Step 3: Calculate each root.

\(k=0: z_0 = 2e^{i\frac{\pi}{6}} = \sqrt{3}+i\).

\(k=1: z_1 = 2e^{i\frac{5\pi}{6}} = -\sqrt{3}+i\).

\(k=2: z_2 = 2e^{i\frac{3\pi}{2}} = -2i\).