Vector Applications in Physics

Vectors are fundamental to physics because they can describe quantities that have both magnitude and direction, such as force, velocity, and acceleration. This chapter explores how vector operations, including the scalar (dot) and vector (cross) products, are used to model and solve problems in mechanics and electromagnetism. We will begin with the principles of force and equilibrium, then move on to describing motion in two and three dimensions.

Newton's Second Law

Sir Isaac Newton's laws of motion form the foundation of classical mechanics. His second law states that the net force \(\sum \Vect{F}\) acting on an object of mass \(m\) is equal to the product of its mass and its acceleration \(\Vect{a}\):$$ \sum \Vect{F} = m\Vect{a} $$

Example

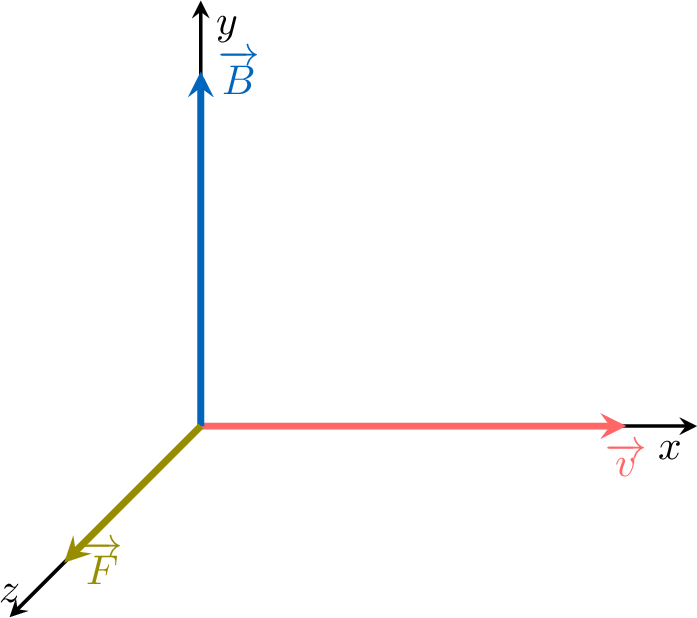

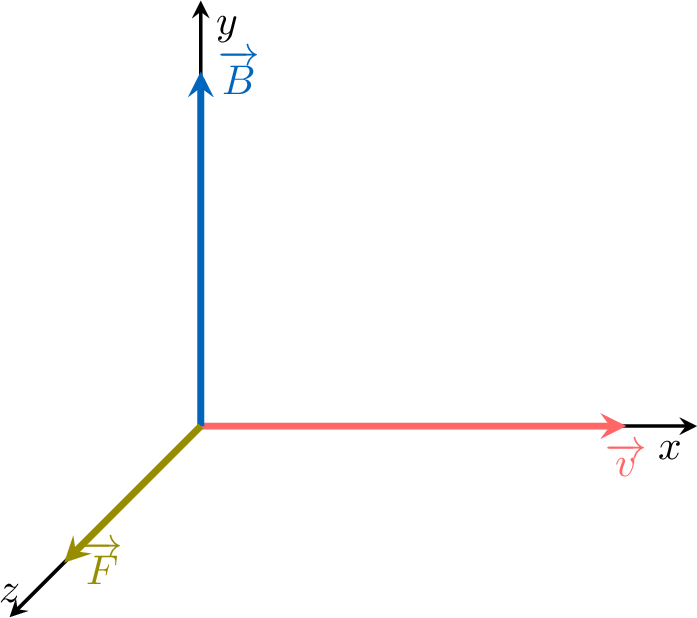

The magnetic force \(\Vect{F}\) exerted on a particle with electric charge \(q\) moving with velocity \(\Vect{v}\) through a magnetic field \(\Vect{B}\) is given by the Lorentz force formula:$$ \Vect{F} = q(\Vect{v} \times \Vect{B}) $$A particle with charge \(q = 1.6 \times 10^{-19}\) C enters a uniform magnetic field \(\Vect{B} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0.5 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\) T with a velocity of \(\Vect{v} = \begin{pmatrix} 2 \times 10^5 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\) m/s, as shown below.

$$\begin{aligned}[t]\Vect{F} &= q(\Vect{v} \times \Vect{B}) \\

&= 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \left( \begin{pmatrix} 2 \times 10^5 \\

0 \\

0 \end{pmatrix} \times \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\

0.5 \\

0 \end{pmatrix} \right) \\

&= 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \begin{pmatrix} (0)(0) - (0)(0.5) \\

(0)(0) - (2 \times 10^5)(0) \\

(2 \times 10^5)(0.5) - (0)(0) \end{pmatrix} \\

&= 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\

0 \\

10^5 \end{pmatrix}\\

&= \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\

0 \\

1.6 \times 10^{-14} \end{pmatrix}\end{aligned}$$The magnetic force acting on the particle is \(\Vect{F} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1.6 \times 10^{-14} \end{pmatrix}\) N. The force acts in the positive \(z\)-direction, perpendicular to both the velocity and the magnetic field.

Velocity and Acceleration with Calculus

According to Newton's Second Law, \(\sum \Vect{F} = m\Vect{a}\): when a net force acts on an object, it causes an acceleration. To describe such motion, we use calculus. The velocity vector is the derivative of the position vector, and the acceleration vector is the derivative of the velocity vector.

Definition Velocity and Acceleration with Calculus

- The instantaneous velocity \(\Vect{v}(t)\) is the derivative of the position vector \(\Vect{r}(t)\) with respect to time:$$ \Vect{v}(t) = \frac{d\Vect{r}}{dt} $$The speed of the object is the magnitude of its velocity vector, \(|\Vect{v}|\).

- The instantaneous acceleration \(\Vect{a}(t)\) is the derivative of the velocity vector \(\Vect{v}(t)\):$$ \Vect{a}(t) = \frac{d\Vect{v}}{dt} = \frac{d^2\Vect{r}}{dt^2} $$

Example

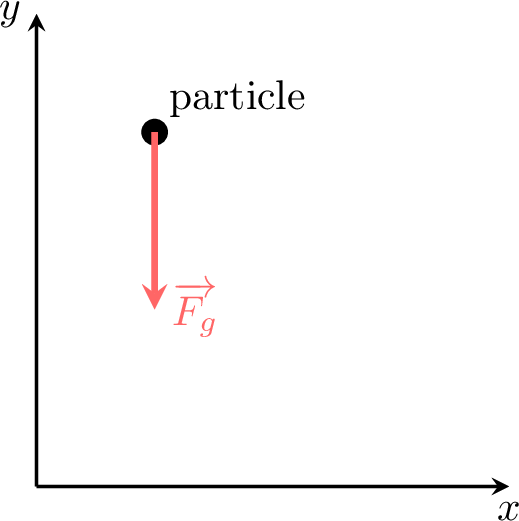

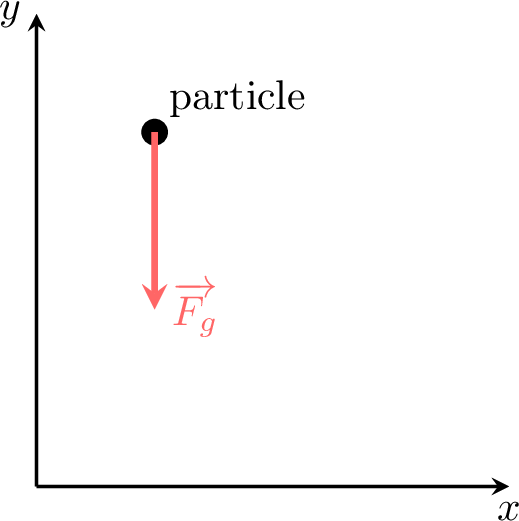

A particle of mass \(m\) is launched with an initial velocity of \(\Vect{v}(0) = \begin{pmatrix} 20 \\ 30 \end{pmatrix}\) m/s. The only force acting on it is gravity, which acts downwards. Find the velocity vector \(\Vect{v}(t)\) of the particle at time \(t\).

The force of gravity near the Earth's surface is \(\Vect{F_g} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ -mg \end{pmatrix}\), where \(g \approx 9.8\) m/s² is the acceleration due to gravity. According to Newton's Second Law, \(\sum \Vect{F} = m\Vect{a}\). Since gravity is the only force, the acceleration vector \(\Vect{a}(t)\) is:$$ m\Vect{a} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\

-mg \end{pmatrix} \implies \Vect{a} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\

-g \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\

-9.8 \end{pmatrix} \text{ m/s²} $$The acceleration is constant and directed downwards. To find the velocity vector \(\Vect{v}(t)\), we integrate the acceleration vector:$$ \Vect{v}(t) = \int \Vect{a}(t)\, dt = \int \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\

-9.8 \end{pmatrix} dt = \begin{pmatrix} C_1 \\

-9.8t + C_2 \end{pmatrix} $$We use the initial condition \(\Vect{v}(0) = \begin{pmatrix} 20 \\ 30 \end{pmatrix}\) to find the constants of integration \(C_1\) and \(C_2\):$$ \begin{pmatrix} 20 \\

30 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} C_1 \\

-9.8(0) + C_2 \end{pmatrix} \implies \begin{pmatrix} C_1 \\

C_2 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 20 \\

30 \end{pmatrix} $$Therefore, the velocity vector at time \(t\) is \(\Vect{v}(t) = \begin{pmatrix} 20 \\ 30 - 9.8t \end{pmatrix}\) m/s.

Motion with Constant Velocity

According to Newton's Second Law, \(\sum \Vect{F} = m\Vect{a}\). When the net force acting on an object is zero (\(\sum \Vect{F} = \Vect{0}\)), its acceleration is also zero (\(\Vect{a} = \Vect{0}\)).

We can find the velocity by integrating the acceleration vector with respect to time. Since the acceleration is the zero vector, we have:$$ \Vect{v}(t) = \int \Vect{a}(t)\, dt = \int \Vect{0}\, dt = \Vect{C} $$The result is a constant vector, \(\Vect{C}\). This means the velocity does not change over time. This constant velocity is simply the object's initial velocity, which we will call \(\Vect{v_0}\).

Next, we find the position vector by integrating this constant velocity vector \(\Vect{v_0}\):$$ \Vect{r}(t) = \int \Vect{v_0}\, dt = t\Vect{v_0} + \Vect{D} $$Here, \(\Vect{D}\) is another constant of integration. To find it, we use the initial condition at \(t=0\). The initial position is \(\Vect{r}(0) = \Vect{r_0}\). Substituting this in:$$ \Vect{r}(0) = (0)\Vect{v_0} + \Vect{D} \implies \Vect{r_0} = \Vect{D} $$Thus, the constant of integration is the initial position vector. This gives us the final equation of motion for an object with constant velocity:$$ \Vect{r}(t) = \Vect{r_0} + t\Vect{v_0} $$

We can find the velocity by integrating the acceleration vector with respect to time. Since the acceleration is the zero vector, we have:$$ \Vect{v}(t) = \int \Vect{a}(t)\, dt = \int \Vect{0}\, dt = \Vect{C} $$The result is a constant vector, \(\Vect{C}\). This means the velocity does not change over time. This constant velocity is simply the object's initial velocity, which we will call \(\Vect{v_0}\).

Next, we find the position vector by integrating this constant velocity vector \(\Vect{v_0}\):$$ \Vect{r}(t) = \int \Vect{v_0}\, dt = t\Vect{v_0} + \Vect{D} $$Here, \(\Vect{D}\) is another constant of integration. To find it, we use the initial condition at \(t=0\). The initial position is \(\Vect{r}(0) = \Vect{r_0}\). Substituting this in:$$ \Vect{r}(0) = (0)\Vect{v_0} + \Vect{D} \implies \Vect{r_0} = \Vect{D} $$Thus, the constant of integration is the initial position vector. This gives us the final equation of motion for an object with constant velocity:$$ \Vect{r}(t) = \Vect{r_0} + t\Vect{v_0} $$

Proposition Equation of Motion with Zero Net Force

If the net force on an object is zero, its velocity remains constant. The object's position vector, \(\Vect{r}(t)\), at any time \(t\) is given by the equation:$$ \Vect{r}(t) = \Vect{r_0} + t\Vect{v_0} $$where \(\Vect{r_0}\) is the initial position vector at \(t=0\) and \(\Vect{v_0}\) is the constant velocity vector.

Example

A helicopter is at position \((6, 9, 3)\) and moves with a constant velocity. Ten minutes later, it is at \((3, 10, 2.5)\). Distances are in kilometres. Find the velocity vector and the speed of the helicopter in km/h.

The time taken is 10 minutes, which is \(t=\frac{10}{60} = \frac{1}{6}\) hours. From the equation of motion with constant velocity, \(\Vect{r}(t) = \Vect{r_0} + t\Vect{v_0}\), we have:$$\begin{aligned}[t]\Vect{r}(t) &= \Vect{r_0} + t\Vect{v_0} \\

t\Vect{v_0} &= \Vect{r}(t) - \Vect{r_0} \\

\Vect{v_0} &= \frac{\Vect{r}(t) - \Vect{r_0}}{t} \\

&= \frac{1}{1/6} \begin{pmatrix} 3-6 \\

10-9 \\

2.5-3 \end{pmatrix} \\

&= 6 \begin{pmatrix} -3 \\

1 \\

-0.5 \end{pmatrix} \\

&= \begin{pmatrix} -18 \\

6 \\

-3 \end{pmatrix} \text{ km/h}\end{aligned}$$The speed is the magnitude of the velocity vector:$$\begin{aligned}[t]\text{Speed} &= |\Vect{v_0}|\\

&= \sqrt{(-18)^2 + 6^2 + (-3)^2} \\

&= \sqrt{324 + 36 + 9} \\

&= \sqrt{369} \\

&\approx 19.2 \text{ km/h}\end{aligned}$$