Equations of Lines

There are many applications of vectors in geometry. While some of these applications can be addressed with other tools in 2-dimensional planar geometry, vector methods become particularly efficient and powerful in 3-dimensional space, especially when considering the relationships between lines and planes.

Vector Equation

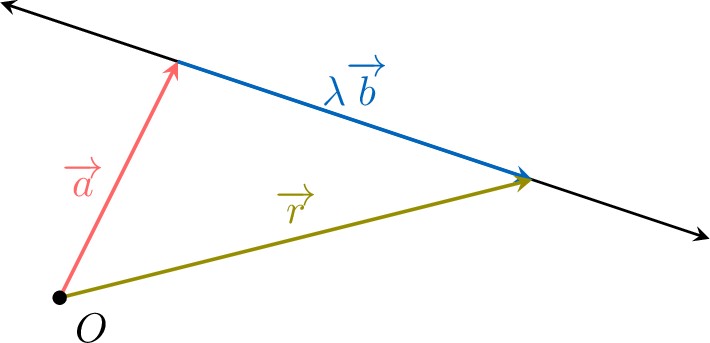

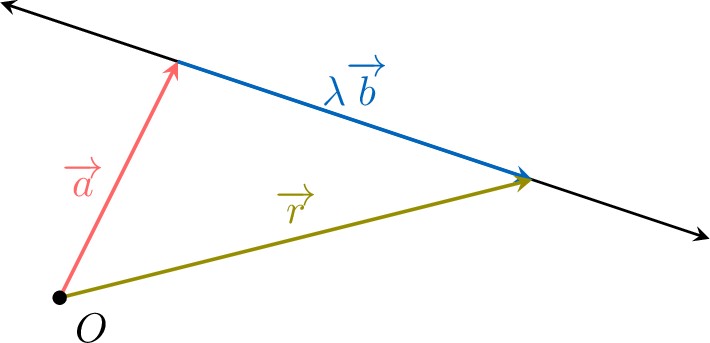

The position of any point on a line can be described by a starting point and a direction of travel. In vector terms, this means that the position vector of any point on the line can be reached by starting with the position vector of a known point and adding a scalar multiple of the line's direction vector. This principle allows us to define a line in both two and three dimensions.

Definition Vector Equation of a Line

The vector equation of the line is:$$ \textcolor{olive}{\Vect{r}} = \textcolor{colordef}{\Vect{a}} + \textcolor{colorprop}{\lambda\Vect{b}}, \quad \lambda \in \R $$

Parametric Equations

Let a line pass through point \(A(a_1, a_2, a_3)\) with direction vector \(\Vect{b} = \begin{pmatrix} b_1 \\ b_2 \\ b_3 \end{pmatrix}\). For any point \(R(x, y, z)\) on the line, the vector equation \(\begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \\ z \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} a_1 \\ a_2 \\ a_3 \end{pmatrix} + \lambda \begin{pmatrix} b_1 \\ b_2 \\ b_3 \end{pmatrix}\) leads to parametric equations: $$ \begin{cases} x = a_1 + \lambda b_1 \\

y = a_2 + \lambda b_2 \\

z = a_3 + \lambda b_3 \end{cases}, \quad \lambda \in \mathbb{R} $$In 2 dimensions, the z-components are simply omitted.

Definition Parametric Equations of a Line

The parametric equations of a line passing through a point \(A(a_1, a_2, a_3)\) with direction vector \(\Vect{b} = \begin{pmatrix} b_1 \\ b_2 \\ b_3 \end{pmatrix}\) are given by the system:$$ \begin{cases} x = a_1 + \lambda b_1 \\

y = a_2 + \lambda b_2 \\

z = a_3 + \lambda b_3 \end{cases} $$where the variable \(\lambda \in \mathbb{R}\) is the parameter.

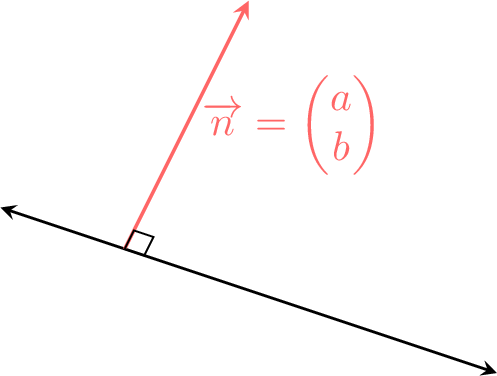

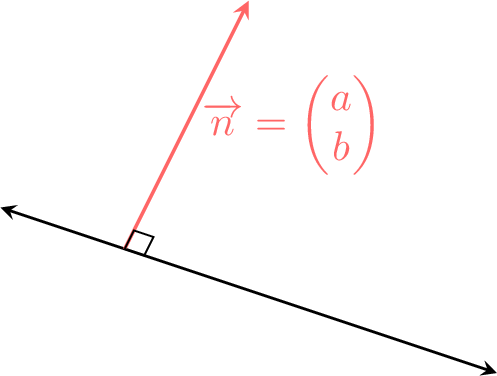

Cartesian Equation in Plane

In two dimensions, a line can also be defined by a normal vector. Let \(\Vect{n}\) be a normal vector to the line's direction, so that \(\Vect{b} \cdot \Vect{n} = 0\).Starting from the vector equation ,\(\Vect{r} = \Vect{a} + \lambda\Vect{b}\), we take the scalar product of both sides with the normal vector \(\Vect{n}\):$$ \begin{aligned} \Vect{r}\cdot \Vect{n} &= (\lambda\Vect{b}+\Vect{a} ) \cdot \Vect{n} \\

\Vect{r}\cdot \Vect{n} &= \lambda\Vect{b}\cdot \Vect{n}+\Vect{a} \cdot \Vect{n}&&\text{(distributivity)} \\

\Vect{r}\cdot \Vect{n} &= \Vect{a} \cdot \Vect{n}&&(\Vect{b} \cdot \Vect{n} = 0) \\

\end{aligned} $$If we let \(\Vect{r} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}\) and the normal vector \(\Vect{n} = \begin{pmatrix} a \\ b \end{pmatrix}\), the expression \(\Vect{r} \cdot \Vect{n}\) becomes \(ax+by\). The term \(\Vect{a} \cdot \Vect{n}\) is a constant, which we can call \(C\). This leads to the familiar Cartesian form.

Definition Cartesian Equation of a Line in 2D

The Cartesian equation of a line in 2D with normal vector \(\Vect{n} = \begin{pmatrix} a \\ b \end{pmatrix}\) is given by:$$ ax + by = C $$where \(C\) is a constant.